Welcome To The Machine 6: Who's Your Daddy?

A Story of Masculinity, Migration, and Myth in America

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

By the late ’80s, my stepfather became my father. Legally. Emotionally? That’s more complicated.

He was my guardian and protector, but more like a big brother—a dutiful but bored chaperone who found respite in the occasional insult or harmless prank. Instead of playing catch, he tossed me insults.

He once told me we were going to Disneyland only to eventually exclaim “April Fools!” I was upset and confused because I didn’t know what April Fools Day was yet. I didn’t get the joke. We never did go to Disneyland.

He also had a short fuse, was prone to road rage and arguments with strangers in public. One of my earliest memories is feelingly deeply concerned for him when a man he was arguing with on the bus smacked him in the face. He could not resist an argument and he always had to win. That rule applied to everyone, even an 8-year old boy.

He didn’t just raise his voice, he unleashed it. Red-faced. Veins bulging. Towering over me, screaming at full volume, sometimes inches from my face. His spit would hit me before his words finished landing. It could last minutes. Five, sometimes ten. Not a conversation. Not a discipline. A purge.

When it started, I’d go quiet. Speak only when prompted. My voice would turn thin and whiny, like an interrogation suspect. It wasn’t fear of punishment, it was fear of him. Depending on my responses, a petty violation could escalate quickly into corporal punishment. On one occasion my mother called the police.

He never apologized. He didn’t know how. The storm would pass, and we’d move on like nothing happened. That’s how I understood masculinity: as pressure with no valve. Power that had nowhere to go but down.

I know now it wasn’t about me. He was fighting his own war that started long before I showed up. His parents divorced and remarried and divorced again. Kosher Kowboy was bipolar, an adulterer, and prone to explosive anger and violence.

My stepfather’s family was fractured, siblings often not on speaking terms. Morther suicidal. He struggled to hold down a job or maintain stable friendships. At the core of his struggles was his rage.

When I was 10 I found his cannabis pipe in the bathroom. I was too young to understand what it was but when he found me looking at it, we were both in this paradoxical situation of getting caught in the act. I recall being reprimanded for my curiosity, I recall his anger being about his own shame.

Cannabis was his medicine, and my mother, who tolerated it at first, began to push him to quit. That only made things worse. He carried rage in his body like it was inherited. And it was.

That was also meant to be my masculine inheritance. Not strength. Not wisdom. Just a template.

I told myself I’d never be like him. But the truth is, when you grow up in the blast radius, something always gets inside you. Maybe not the scream, or the rage, but the shame. The sense that love is conditional. That power is dangerous. That silence is survival.

What I would come to realize is that American masculinity doesn’t just live in men. It lives in systems. It’s in the schools, the media, the politics. It’s in the way God is imagined and power is distributed.

It’s the myth of the strong, rational, self-reliant man descended from cowboys, soldiers, and factory dads. Sometimes he was a president, a pastor, a boss, a coach. Sometimes he was the voice in your head. Sometimes he was your own reflection.

Mad Men

Kosher Kowboy, who was stationed in San Antonio Texas in the 1950s, grew up at a time when films were still young and TV was brand new.

Read about Kosher Kowboy in part 2:

Welcome To The Machine 2: Jokers

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

In the media of the old west, Kowboy was likely given a clear blueprint of the ideal American man:

He was strong, with a mind like a steel trap.

He didn’t ask for help, he gave orders. He didn’t give hugs, he built borders.

He didn’t feel pain, fear, or grief.

He mowed the lawn, paid the bills, fought the wars, and (If lucky) died a martyr.

Previously, Fred Astaire, defined the golden age of the musical, his every step a masterclass in rhythm and intricate choreography. He was the epitome of fluid motion, his dancing an extension of his suave persona.

But something changed after the New Deal. The American man lose the pep in his step.

John Wayne, by contrast, embodied a rugged, unyielding strength. His movements were deliberate, grounded, and purposeful—the gait of a frontiersman or a resolute marshal. He wasn't a dancer. His power lay in his stillness, his imposing presence, and the way he commanded a scene without needing a single pirouette.

The Duke was the architecture of classic American manhood made flesh:

Spartan Discipline: unflinching, emotionally armored.

Old Testament Severity: merciless when necessary, ruled by law, not love.

Protestant Self-Reliance: distrustful, industrious, morally individualistic.

Cowboy Frontierism: untethered, self-governing, defensive.

For non-Protestant natives like Kosher Kowboy and immigrants like my Guyanese grandfather Mr. Khan, assimilation meant accepting this template. You weren’t just learning the customs, you were learning how to be a man, in the image of the West.

But behind the stoic veneer of the American Man was a quiet rage—part bitterness, part defensiveness—that was fundamental to how and why he operated. The American Man was on a mission: to preserve his way of life and defend his property.

Manifest Destiny ordained him a steward of all of humanity. American exceptionalism solidified that rule in blood and GDP.

Read about America’s journey from isolationist republic to global empire in Part 4:

Welcome to the Machine 4: America

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

Cocaine Cowboys

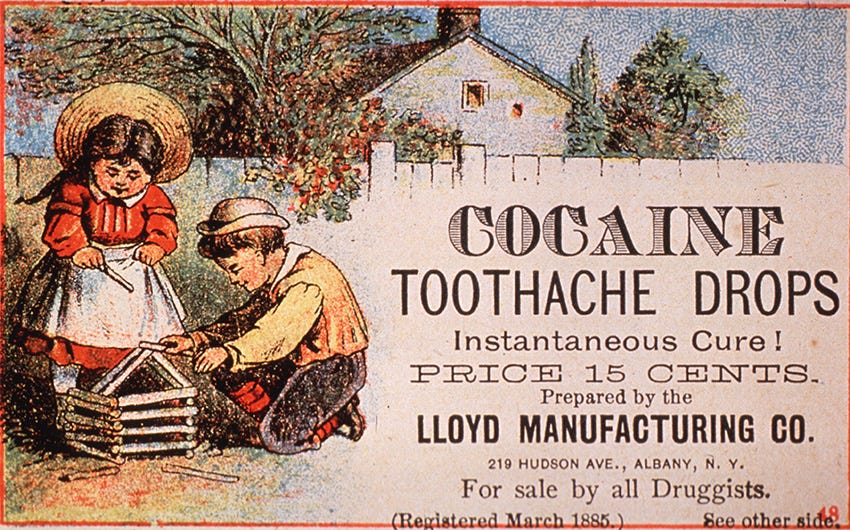

In the evolving narrative of the American male, certain crucial drugs have woven themselves into the fabric of daily life and coping mechanisms, each reflecting societal shifts and class distinctions.

Cocaine first started coming into America and gaining popularity in the mid-1880s. Similar to the opiates used by Chinese laborers in the west, the drug was often provided to black workers based on pseudoscientific reports that claimed cocaine rendered Black individuals "impervious to the extremes of heat and cold".

These claims also created a perception of Black men as dangerous and 'impervious to bullets and to the extremes of heat and cold' when under the drug’s influence."

Cocaine was soon touted as a "medical wonder drug" and was freely available in drug stores, often as an ingredient in various medicines, tonics, and even the original Coca-Cola formula.

Its use peaked between 1900 and 1915, becoming increasingly fashionable among upper classes. However, public perception shifted as its addictive properties and negative side effects became apparent.

Read about the concurrent rise of nativism and eugenics during this period here:

Welcome To The Machine 3: The Muscle

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

Marlboro Men

But by 1913, cigarettes were on the market as the new legal stimulant.

Tobacco, initially vital as an early cash crop that shaped the nation's economy, had transitioned into the ubiquitous, addictive, and eventually deadly cigarette, becoming a seemingly indispensable companion in work and leisure.

A clear trend emerged: stimulants like cocaine and nicotine found favor among the upper classes, serving as a means for "enhancement"—to meet the demanding pace of industry and ambition.

Meanwhile, depressants like whiskey and moonshine often became the coping mechanism for the poor, offering an escape from hardship and the grind of daily life.

The common thread among these substances was their fundamental promise: they offered a way to cope with the world's demands, whether through heightened focus or numbing escape, yet critically, they did not significantly challenge the ego, nor did they profoundly alter one's consciousness in a way that truly broke from reality.

They allowed for existing perceptions to persist, providing either a sharper edge or a softer blur to the same demanding world.

The Devil’s Lettuce

After the New Deal, as Black Americans migrated North, a panic took hold: "Black culture infecting white culture!"

Jazz, Blues, R&B… Black art was exploding, undeniably vital, and crossing lines. This thrilled youth, but terrified an establishment clinging to racial purity. Media, simultaneously broadcasting and demonizing, amplified the fear of moral decay and miscegenation.

As the Jazz Age pulsed and the Great Migration shifted demographics, a new specter was conjured: the rumor of Black men, fueled by cannabis, driven to rape white women.

It was a deliberately crafted hysteria posing as public health concern—a precision weapon in the ongoing war of control and criminalization against Black and Indigenous men.

American Idol

Elvis Presley was the first mass-produced American male idol. He fused Black sound with white skin, sexual energy with safe patriotism. He thrilled teenagers and terrified parents simply with the way he danced.

After the 1950s, Elvis was folded back into the system. He joined the army.

He made Hollywood movies. He became respectable. He became the very embodiment of the lucrative, entertainment-driven music industry.

The Counter-Counterculture

The John Birch Society, founded in 1958 by candy magnate Robert Welch, was the first major attempt to organize right-wing paranoia into a cohesive ideology. They opposed civil rights, feminism, fluoride in drinking water, and the United Nations.

To them, Martin Luther King Jr. was a communist. So was Eisenhower.

But beneath the conspiracies was a deeper story: a version of masculinity built on fear of collapse. They saw the rise of collectivism (in economics, art, education, and emotion) as a threat to the self-contained, dominant American male.

JBS introduced millions to the idea that a shadowy, powerful group was orchestrating global events to merge nations into a totalitarian world government, thereby establishing many of the core themes that would be central to globalist conspiracy theories for decades to come.

The Birchers planted seeds that would bloom decades later in Reaganism, libertarianism, the militia movement, and eventually online red-pill culture.

Bob Dylan, emerging from the smoky coffeehouses of Greenwich Village in the 1960, challenged the JBS directly. He represented a different kind of insurgency. The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963), rattled public consciousness with sprawling, poetic broadsides against injustice, war, hypocrisy, and the apathy he saw permeating society.

Shaken But Not Stirred

In the early 1960s, the American man still looked like the blueprint. He was stoic, rational, dominant. He wore a gray suit, went to work, and kept his feelings in check. He followed the rules because the rules worked, for him. And when they didn’t…

Sean Connery’s James Bond was a mythic father in “modern” packaging; licensed to kill, immune to grief. He didn’t bend or break. He conquered, seduced, moved on. The Cold War needed a face, and Bond gave it one: smooth, cruel, Western. He also normalized the kind of espionage the US and CIA were engaged in.

In 1964, while the US was actively staging a coup against the popular Socialist leader of Guyana, it was also creating a pretext to obtain Vietnam's offshore oil with the The Gulf of Tonkin incident. But there, the Empire found itself outmatched, not by conventional armies, but by an unseen enemy, a relentless force of guerrilla fighters woven into the very fabric of the land.

Read about the covert operations of the CIA in Guyana in Part 1:

Welcome to the Machine 1: The Son

Welcome to the Machine is a longform essay series tracing the fractured soul of the American man, through migration, masculinity, media, and myth. It’s part cultural retrospective, part personal excavation.

Dropouts

During this era, the CIA embarked on Project MKUltra, a highly controversial program that extensively experimented with LSD and other psychoactive drugs from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s.

These experiments often involved administering LSD to unwitting subjects, including civilians, without their consent, sometimes resulting in severe psychological harm and even death, highlighting a dark chapter of ethical misconduct in government research.

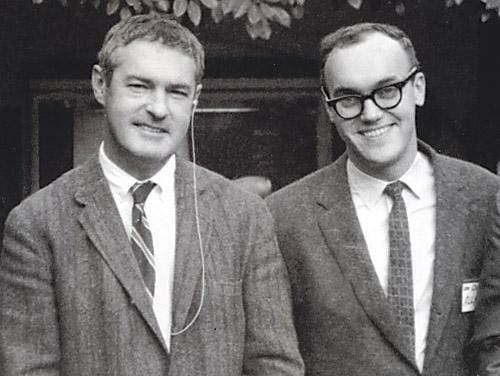

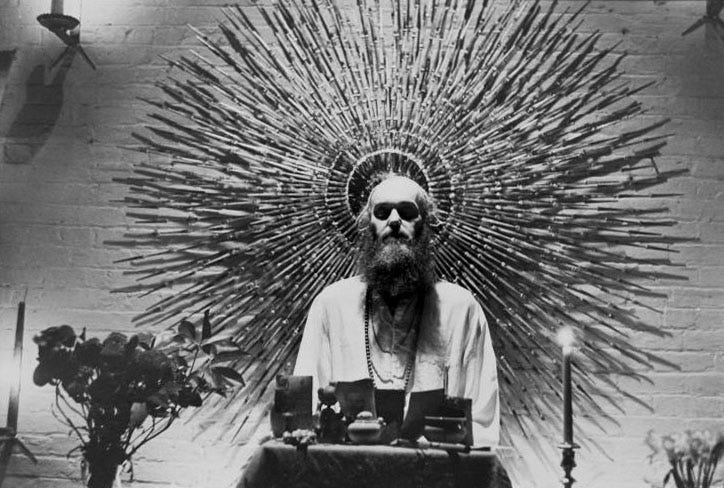

In the 50s and 60s, LSD (primarily a research drug) began to leak out of clinical settings, notably through figures like Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass) at Harvard University, who promoted its use for spiritual and consciousness expansion, initially with psilocybin and then LSD.

Cannabis, LSD, psilocybin, mescaline—none of them made sense inside the rigid framework of American masculinity. These weren’t stimulants or party drugs. They were spiritual wrecking balls. But ego death wasn’t compatible with Cold War stoicism.

There was no training for inner surrender. The rational, goal-oriented man had no language for what he was seeing. In the American imagination, those things smelled like laziness, softness, or worse, socialism. The very idea of a shared inner life was threatening to a culture built on personal ownership.

Dose Beatle

The Beatles arrived as clean-cut boys in matching suits, but by decade’s end,

they were barefoot mystics channeling something ancient and unspoken.

In 1965, a peculiar and pivotal moment in rock history unfolded when George Harrison and John Lennon, along with their wives, were unknowingly given LSD by their dentist, John Riley, during a dinner party.

The music grew stranger. They met Bob Dylan. The suits disappeared. The lyrics turned inward, spiritual, surreal. They stopped touring. They stopped obeying. They began pulling apart the scaffolding that built them.

George Harrison introduced Eastern spiritual ideas into Western youth culture, not as rebellion but as invitation.

John Lennon went further, pulling apart nationalism, capitalism, and organized religion with a calm, radical clarity.

Say It LOUD

Funk music emerged in the mid-1960s, primarily out of the foundational elements of soul, jazz, and rhythm and blues, driven by artists seeking to emphasize a more rhythmic, danceable groove.

Pioneered by figures like James Brown, who famously demanded "the one" (the first beat of the measure) funk stripped away melodic complexity in favor of strong, syncopated basslines, sharp horn arrangements, and a percussive focus that made the body move almost instinctively.

This shift wasn't merely musical; it reflected a cultural moment, providing a vibrant soundtrack to an era of evolving social dynamics and Black cultural pride.

At the same time, the civil rights movement was reshaping public life and public manhood. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Huey Newton, and Stokely Carmichael offered a counterpoint to the dominant masculine myth.

Their power came not from silence, but from speech. Not from stoicism, but conviction. Their presence redefined dignity, discipline, and public strength. For white men raised on lone heroes and inherited superiority, this was destabilizing. It forced a confrontation with both history and identity.

Jimi Hendrix wasn’t just a good guitar player, he was freer. Louder. Stranger. More fluid. Because he had experienced something sacred. He didn’t just play guitar, he redefined it. White audiences (men and women alike) were mesmerized. For many, this was thrilling. For others, it was threatening.

He bent sound the way the Beatles were beginning to bend reality. And he was a Black man doing it better than the icons they grew up worshipping. His rise was artistic but also existential.

A quiet anxiety was also forming: the hero on stage didn’t look like them anymore.

Free Men

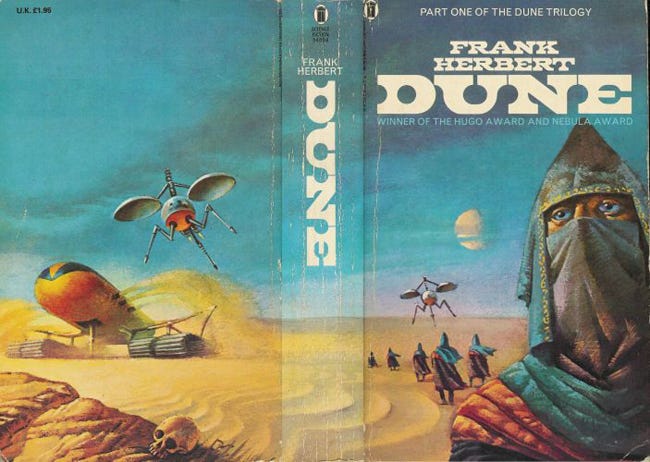

Dune (1965) is set on the harsh desert world of Arrakis, where the vital Spice is found, its narrative not-so-subtlety mirroring the real-world scramble for oil, and the uncomfortable presence of outside powers in places like Iraq in the Middle East.

You couldn't help but see the Fremen, those fierce, desert-dwelling people with their deep faith and survival instincts, as reflections of Arab and Bedouin cultures, forced to resist empires intent on exploiting their land and its hidden wealth.

Paul's journey to becoming the Fremen's messiah, Muad'Dib, is deeply intertwined with his understanding and manipulation of language, prophecy, and the Fremen's deeply ingrained belief system, much of which was seeded by the manipulative Bene Gesserit themselves.

His command of the Fremen's language and his ability to fulfill their prophecies makes him a powerful, even dangerous, figure.

Much of Dune's DNA found its way into other cultural touchstones, like Star Wars with its own desert planet Tatooine.

The Enterprise Strikes Back

While Dune often plunged into the grit of desert survival and the perspective of a people resisting a distant imperium, Star Trek (1966), showed us a completely different angle—from the starship bridges, with the officers in their pristine uniforms, making top-down decisions that affect entire populations on planets they might only ever see through a viewscreen.

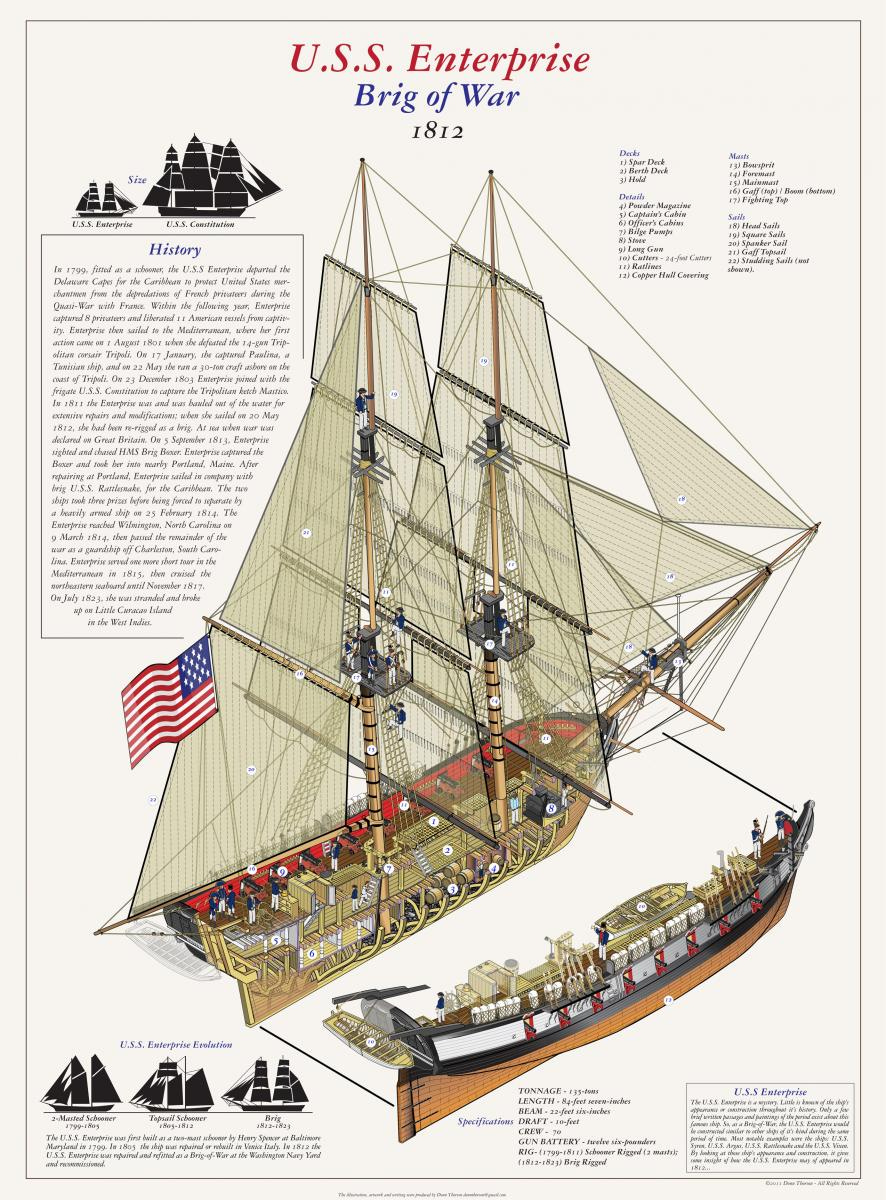

Their ship, Enterprise, was named after the infamous US navy vessel of WW2—a name whose legacy dates back to 1799 and the war ship that fought the first US war abroad, the Barbary Wars against the Northern African States. The victory assured free and safe trade routes in the Mediterranean.

The crew of the Enterprise were supposedly on a journey of discovery and exploration. Charting a brave new frontier, armed with phasers and deadly photon torpedos, which were of course necessary to combat hostile indigenous populations.

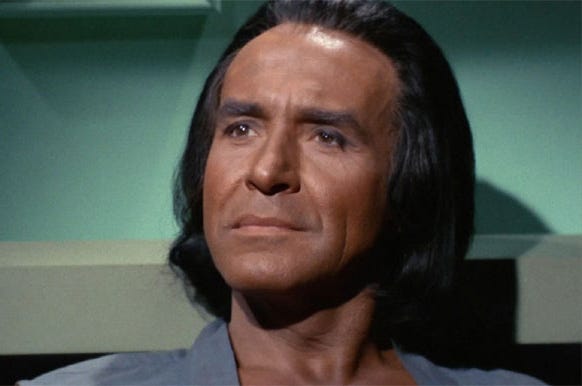

Among its most memorable figures was Khan a genetically enhanced warlord, cast ambiguously brown, written as foreign, and coded with intelligence and vengeance. He wasn’t part of the show's liberal vision of harmony. He was its shadow. A man with power and brilliance, born of Eugenics, exiled and erased.

Khan’s presence reflected a deeper anxiety about masculinity unbound from Western civility—too strong, too alien, too proud. He was a product of humanity’s worst horrors and had come back to haunt them.

Even his name, pulled from South Asian royalty, carried weight.

Black American Idol

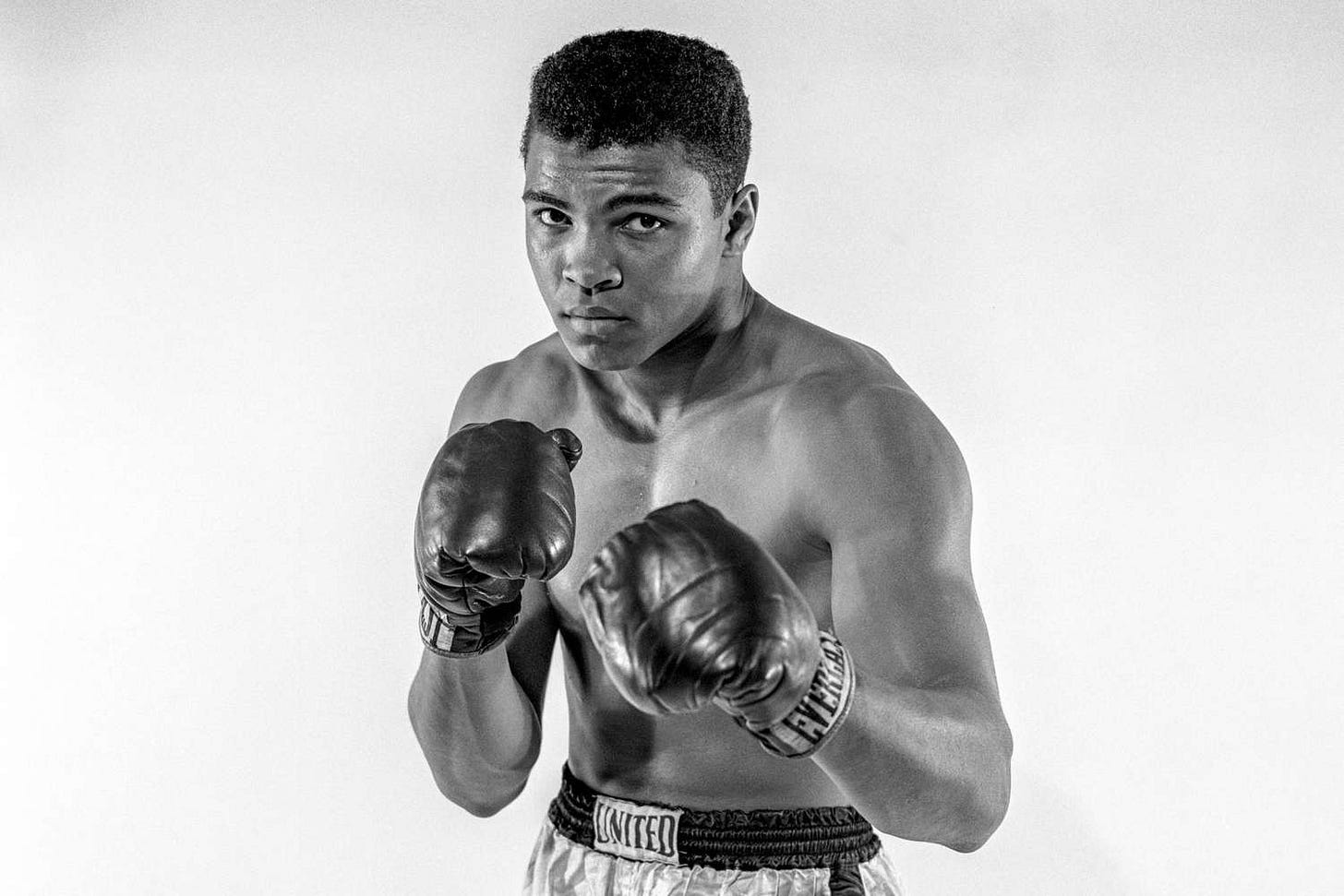

Figures Muhammad Ali in sports, Richard Pryor in comedy, and Sidney Poitier in film weren’t just talented, they were also revolutionaries in their fields.

The rise of stars like Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and Bill Cosby by the late ’70s and early ’80s created an image of upward momentum, an era when Black celebrity seemed to signal real racial progress.

On screen, shows like Good Times (1974) and The Jeffersons (1975) gave many Americans their first consistent depictions of upwardly mobile Black families.

But this visibility often masked deeper inequality. While Black celebrities were gaining unprecedented cultural power, poor Black communities continued to face systemic poverty, redlining, police brutality, and failing schools. Racial tension still gripped much of rural and suburban America.

On the surface, things looked better. But underneath, the old machinery of racism had simply adapted, not disappeared

American Joe

In the late 1970s, Rocky emerged as more than just a boxing film. It became a profound expression of white male anxiety, particularly resonating with working-class communities in cities like Philadelphia and Brooklyn.

Read about more of this anxiety in the last entry:

Welcome To The Machine 5: Mob Rules

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

Apollo Creed, with his dazzling showmanship and patriotic regalia, embodied the triumphant, new face of America.

In stark contrast, Rocky Balboa, the "Italian Stallion," became the underdog hero: a gritty, working-class figure slaving away in meat lockers, his quiet despair a familiar echo for many disgruntled white Italian American males struggling to find their footing in a changing economic landscape.

His improbable shot at the championship, culminating in a victory that felt like a win for every downtrodden "Joe," tapped into a complex sense of neglect and a yearning for validation.

For this audience, Rocky's heart and resilience, more than a literal win in the ring, cemented him as the authentic, unsung hero, representing the enduring spirit of those who felt overlooked by the very nation whose colors Apollo proudly wore.

We’re Not Gonna Take It

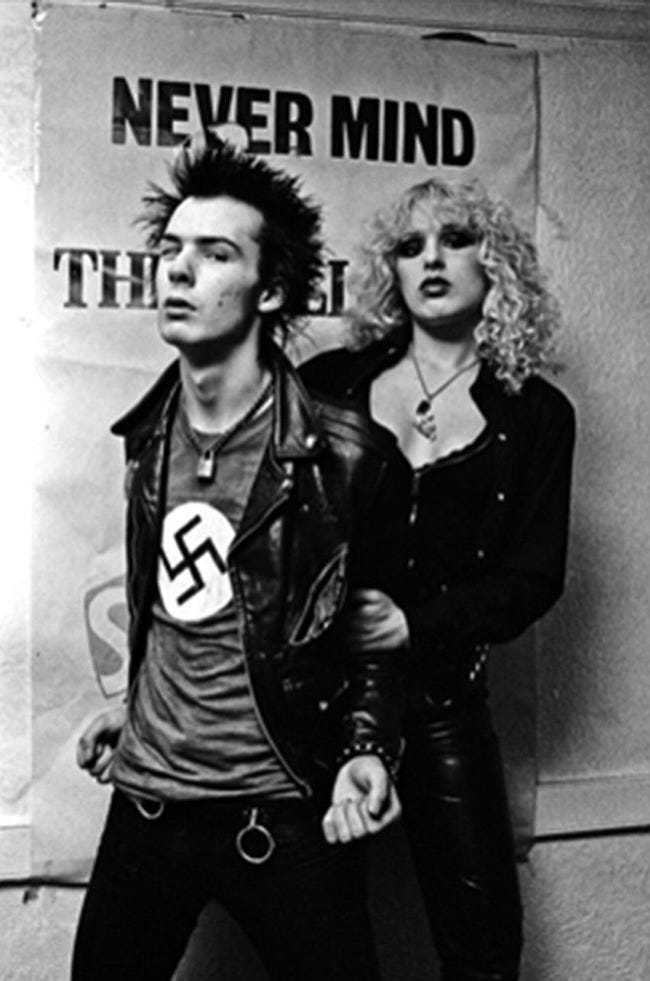

Meanwhile, music splintered. For white working-class men who didn’t see themselves in psychedelia or disco, punk and metal offered another way forward—louder, faster, and angrier.

Punk stripped music down to raw defiance: three chords, no future. It was rebellion without illusion, masculinity expressed through sneer and sweat.

Metal, on the other hand, mythologized rage. The guitars got heavier. The lyrics turned to war, madness, and apocalypse.

Bands like Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, and later Metallica gave voice to a generation of men who felt abandoned by the system their fathers built.

A New World Daddy

Carter had asked Americans to conserve, to reflect, to endure limits. Reagan offered the opposite. Optimism. Simplicity. A smiling return to greatness. He promised that America was still the hero.

That problems could be outspent, outfought, and out-imagined. Masculinity didn’t need humility, it needed a soundtrack and a slogan. Where Carter asked for sacrifice, Reagan delivered the illusion of abundance.

New World Order

The John Birch Society (JBS) played a significant and early role in popularizing and disseminating what would become key tenets of the New World Order (NWO) conspiracy theories in the United States.

JBS argued that global communism was not a grassroots movement, but rather a tool wielded by a secretive, powerful elite intent on establishing a one-world government.

They often referred to this supposed cabal as "insiders" or "the Conspiracy," believing this group was manipulating global events from behind the scenes to achieve their goal of a socialist world order.

The JBS saw international organizations like the United Nations, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Trilateral Commission as instruments of this conspiracy, rather than legitimate bodies for international cooperation. They warned that these entities were stealthily eroding national sovereignty and individual liberties.

While the term "New World Order" gained broader currency later, particularly in the 1990s, the JBS's extensive publications and activism in the 1960s and 70s laid much of the groundwork.

The REAL American Hero

Pop culture doubled down.

G.I. Joe (1982) was rebooted with a new villain, a terrorist organization called Cobra, which was also a multi-level marketing scheme.

He-Man, Rambo, WWF Superstars… The message was the same: strength wins. The villains were foreign, monstrous, or both. Heroes were mostly white, shredded, and patriotic.

Professional wrestling turned the myth into pure spectacle. Hulk Hogan waved the flag and dropped the leg on cartoon communists and ethnic heels. It wasn’t subtle, but it worked. Young boys absorbed it as gospel.

The Right Religion

In the 1980s, the religion of American males increasingly merged with nationalism, capitalism, and spectacle.

Traditional Protestant values remained strong, especially in the South and Midwest, but were now intertwined with the rise of the Religious Right, driven by figures like Jerry Falwell who framed conservative Christianity as a bulwark against feminism, communism, and moral decline.

At the same time, money and success became sacred, Wall Street ambition, self-help gurus, and prosperity gospel preaching all sanctified power and wealth. For many men, belief in God coexisted with a growing faith in markets, masculinity, and American exceptionalism.

Not quite atheism, it was substitution. The church was still there, but so were gyms, stadiums, and boardrooms, where performance replaced devotion and domination became its own kind of spiritual path.

Branded Rebellion

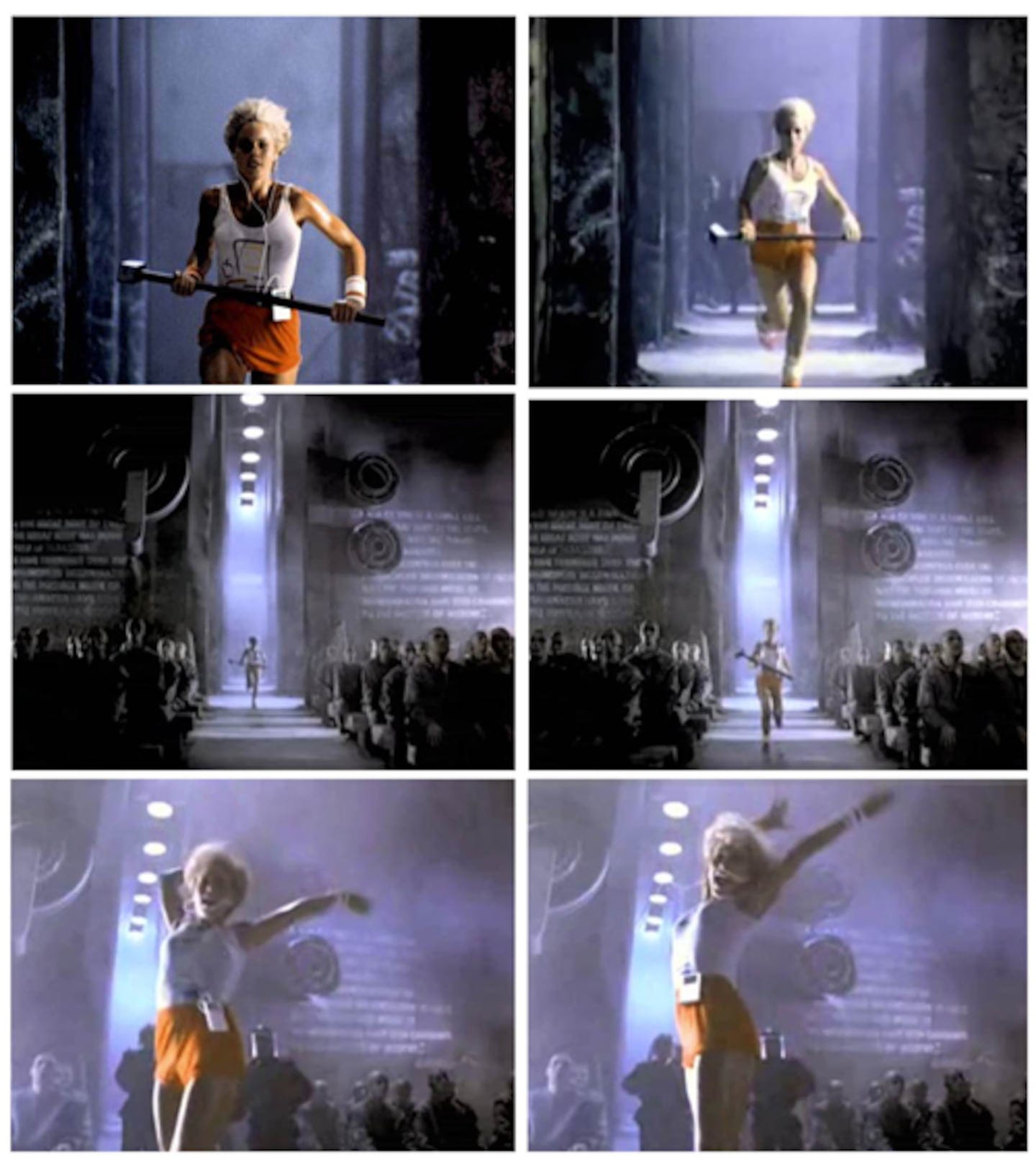

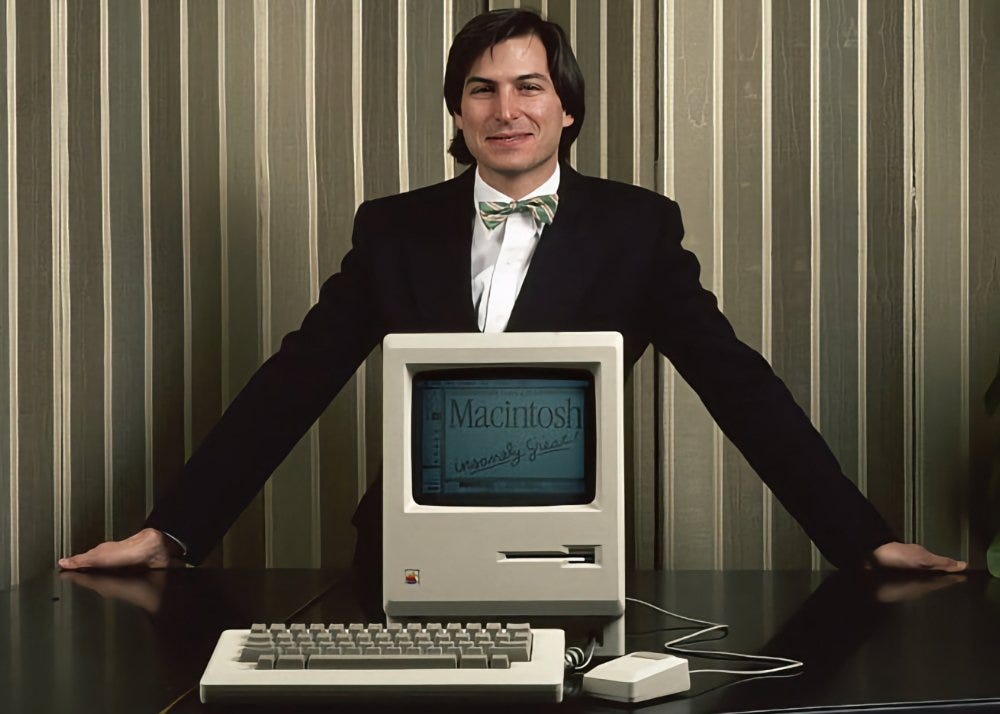

In 1984, Apple released a Super Bowl ad that would become one of the most iconic in American history. Directed by Ridley Scott, it presented a bleak, totalitarian world where an army of bald-headed drones watched Big Brother deliver a speech on conformity. Then, a woman sprinted into the frame with a sledgehammer and destroyed the screen, shattering the system and “freeing” the masses. The final message:

On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh.

And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.

The imagery was lifted directly from Orwell’s novel. But the meaning had flipped.

In the commercial, Big Brother was IBM. The rebellion wasn’t against the state, it was against corporate sameness. And the solution wasn’t revolution, it was a product.

This was the beginning of branded rebellion: selling freedom, individuality, and even dissent as a lifestyle choice.

Steve Jobs was the self-made entrepreneur, the visionary outsider

who didn’t need government, just belief in himself.

Where Reagan celebrated cowboys and astronauts, Jobs became the digital frontiersman, exploring new worlds through design and code instead of land and war.

It was pure Reagan-era contradiction. Jobs, who came out of the LSD-Zen-Californian counterculture, had become a prophet of the consumer age. The hippies had become CEOs. The tools of personal liberation were now being sold through million-dollar ad buys during football games.

The commercial showed how easily resistance could be stylized. How the aesthetics of rebellion could be used to sell conformity. How “Think Different” would become a trademark.

In hindsight, the ad feels like a magic trick. It invoked Orwell to cast a spell. And it worked.

The Austrian School

A new masculine image was also being sculpted, literally. Arnold Schwarzenegger emerged as the body of the decade. First through bodybuilding, then through Conan the Barbarian, where he declared without irony that the best thing in life was “to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear the lamentation of their women.”

It was a creed. Muscles, domination, conquest, sex, survival. Arnold became a walking ideal; part myth, part machine. From Conan to Commando to Predator, Arnold was redefining what a man should look like, act like, and kill like. For a generation of boys, he was the new mold.

Fox In the Hen House

The emergence of the Fox network in the late 1980s marked a significant cultural shift, giving rise to programming that spoke to a changing American landscape, often with a raw, unvarnished honesty.

At its heart was Married... with Children, which introduced the nation to Al Bundy, a new kind of American male hero, or rather, anti-hero. Far from the aspirational figures of earlier sitcoms, Al was a tragic, often pathetic figure, trapped in suburban drudgery and marital strife.

Yet, his relentless cynicism and relatable failures resonated deeply, offering a voice to those who felt left behind by the American dream.

Soon after, The Simpsons arrived, presenting what appeared to be a typical American family living in the archetypal "nowhere" town of Springfield. Homer Simpson, with his endearing flaws and childlike impulses, offered another playful yet acutely real glimpse into the complex, sometimes chaotic dynamics playing out in family homes across the country.

As Fox News later rose to prominence, advocating for a specific political viewpoint, the lines between entertainment and reality, satire and commentary, began to blur profoundly.

The process of art imitating life imitating art continued to roll on, but now with a deeply conflicted, almost adversarial, relationship with objective truth. The networks, and the characters they championed, became reflections and shapers of a fractured national identity, where reality itself seemed increasingly subjective.

A Kinder, Gentler Empire

The phrase "kinder, gentler nation" was a prominent political slogan used by George H.W. Bush during his 1988 presidential campaign.

While Bush initially rode a wave of popularity, inheriting much of Reagan's legacy and benefiting from the collapse of the Soviet Union, underlying domestic anxieties began to surface.

This re-focus on domestic economic woes, combined with Bush's perceived broken promise of "no new taxes". Through the 1990 budget agreement, which he signed into law. This agreement increased the top income tax rate from 28% to 31% and also raised taxes on some luxury goods and other items.

The First Gulf War, launched in 1991, initially provided a massive surge in President Bush's approval ratings, reaching unprecedented heights as the swift military victory fueled national pride and a sense of renewed American strength.

This is what provoked my Dad to sell American Flags on the side of the road in the dead of winter. During this time, my mother was pregnant with my half-sister and we needed all the money we could get.

Bush's perceived lack of focus on these "bread and butter" issues, famously summarized by James Carville's campaign mantra for Bill Clinton, "It's the economy, stupid," proved to be his undoing. Voters felt disconnected from the administration's priorities.

The election of Bill Clinton in 1992, a "New Democrat" who effectively campaigned on economic revitalization and a more centrist platform, signaled a decisive shift in power and a move away from two decades of Republican presidential dominance, ushering in a new era of Democratic leadership.

By the 90s, my stepfather got a job as a “computer operator”, one of many computer-related career paths opening up in the new frontier.

This would unfortunately lead to a series of disposable roles for companies that failed to generate profit during the dot com era.

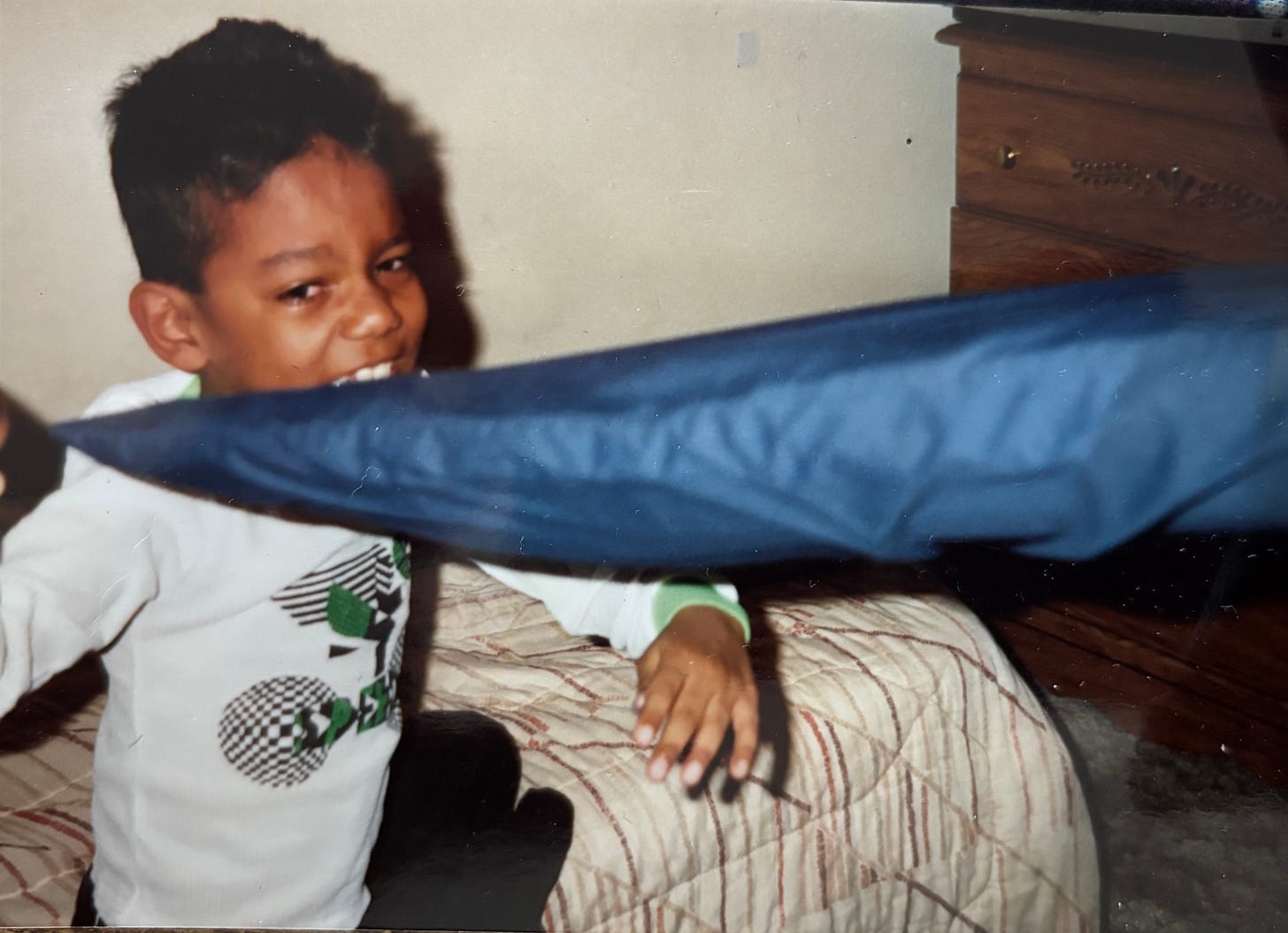

American Boy

In the early ’90s, I became a disciple of American media. Saturday morning cartoons. Action movies. Sitcoms. Comic books. Cable TV was my babysitter, my teacher, my spiritual guide.

And I wasn’t alone. My generation was full of boys internalizing the same imagery. Power came in the shape of muscle-bound men with guns, gadgets, or magical destinies based on heritage or blood.

Batman. Wolverine. Arnold. Luke Skywalker. Every story taught us the same thing: if you want to matter, you have to fight, win, dominate, or transform. Even mutant ninjas could be vigilantes, as long as they stayed buff and in the shadows of the system.

There were only two types of families on TV: white or Black. There was no family like mine. No brown kid with a Guyanese Muslim mother and a Jewish American stepfather living in Brooklyn. So I gravitated to the characters I was supposed to relate to: white boys.

I wanted Bart Simpson’s hair, even though mine wouldn’t spike. I didn’t want to be white—I wanted to be the main character. The chosen one. The protagonist.

Sensitivity was for side characters. For weirdos. For villains. Even the “funny friend” had to prove himself in the end by getting tough or taking a punch.

My stepfather understood this. He took me to see every Arnold movie, usually on opening weekend. It was our one consistent father-son ritual.

He signed us both up for Taekwondo but I never made it beyond white belt because he canceled our classes after an argument with the sensei about the lack of practical self-defense techniques.

He took “before” pictures of my scrawny frame and tried to get me lifting weights. But coach tapped out when we had an argument about my lack of interest.

He wanted me to bulk up, toughen up, but I was an effeminate, goofy kid who liked to draw and cried at the end of Son of Godzilla.

I didn’t want to be a warrior. I didn’t have a reason to fight.

I wasn’t angry, yet.