This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

In 1985, I arrived in the South Bronx with my mother, a small suitcase, and no father. What I didn’t know then was that America had already decided what kind of man it wanted me to become. If you want to know the important role my home country Guyana played in world wars, read Part 1: The Son.

Into The Flames

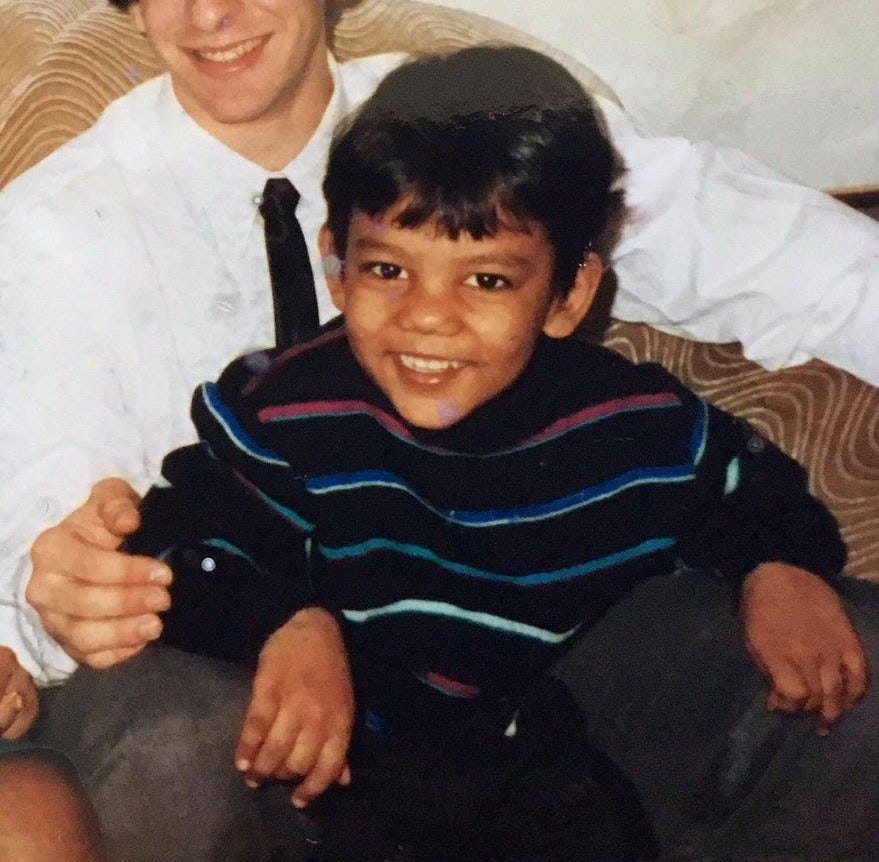

After about a year of living in the Bronx, my mother took me down to Coney Island to meet someone. It was practically the same trip The Warriors took in 1979 but it about a half an hour longer than the runtime of the film. I was shy and quiet, as the photos from that day still show.

I remember riding the carousel on Stillwell Avenue (just down the block from the famous Cyclone) and slipping into a kind of soft, melancholic trance. I don’t know why. Maybe it was the long train ride, maybe it was the vibe of that place.

We made the trip a few more times (him to us, us to him) and slowly, I warmed to this young man. It was hard not to.

He was FUNNY.

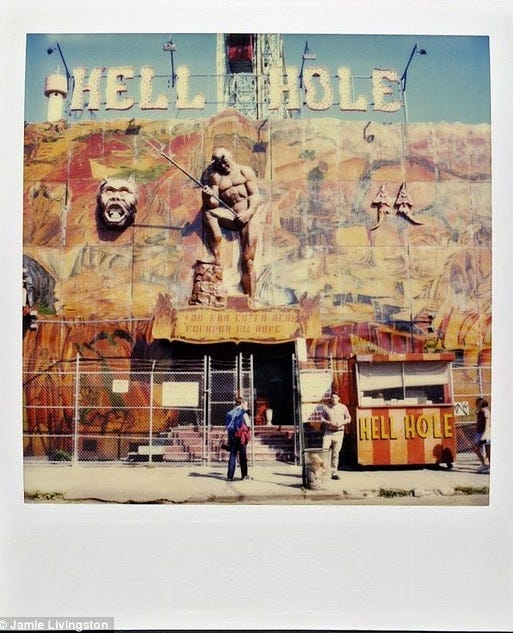

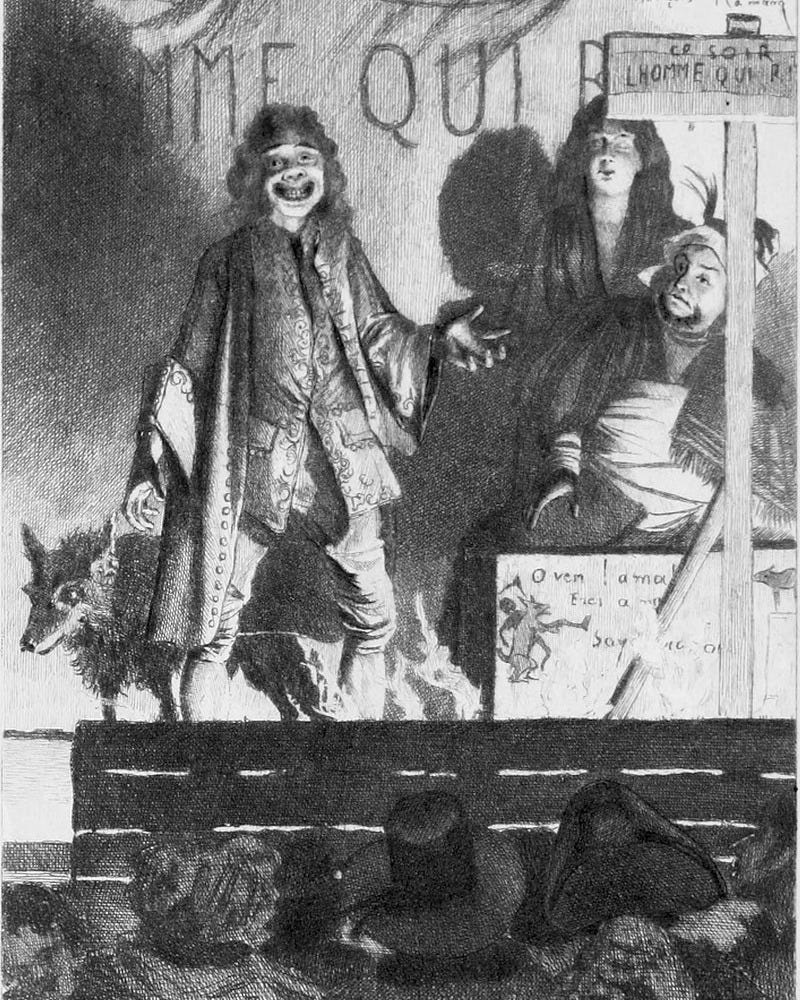

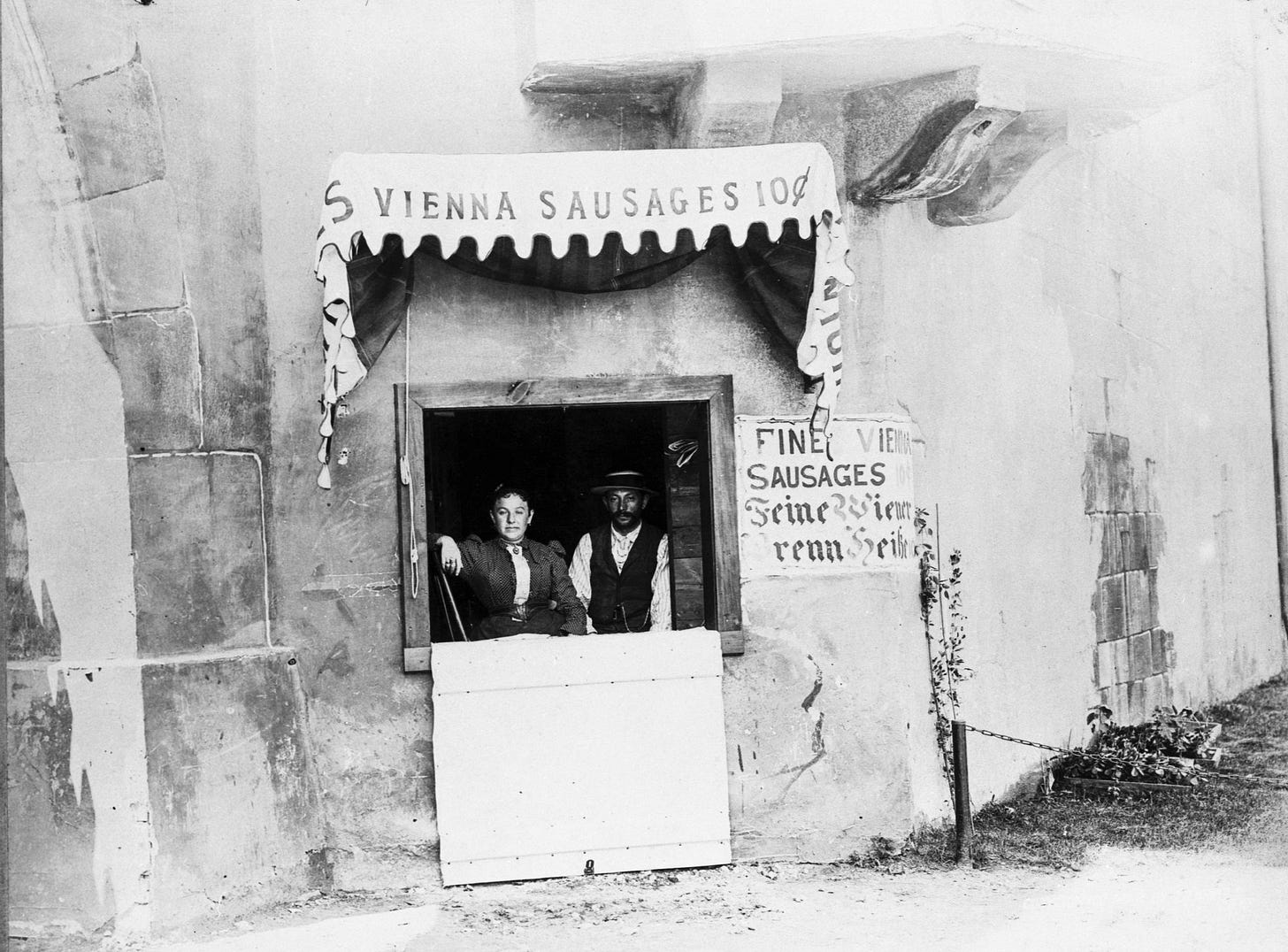

Here he is in the late 70s at the annual Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, which took place just down the block from where he lived:

He played me his records: “Suzy Creamcheese” by Frank Zappa and George Carlin skits about petting cats. We watched WWF together and carefully flipped through his Spider-Man collection and MAD Magazines. Masters of the Universe (1987) was the first film he took me to see, kicking off what became an almost weekly father-son tradition.

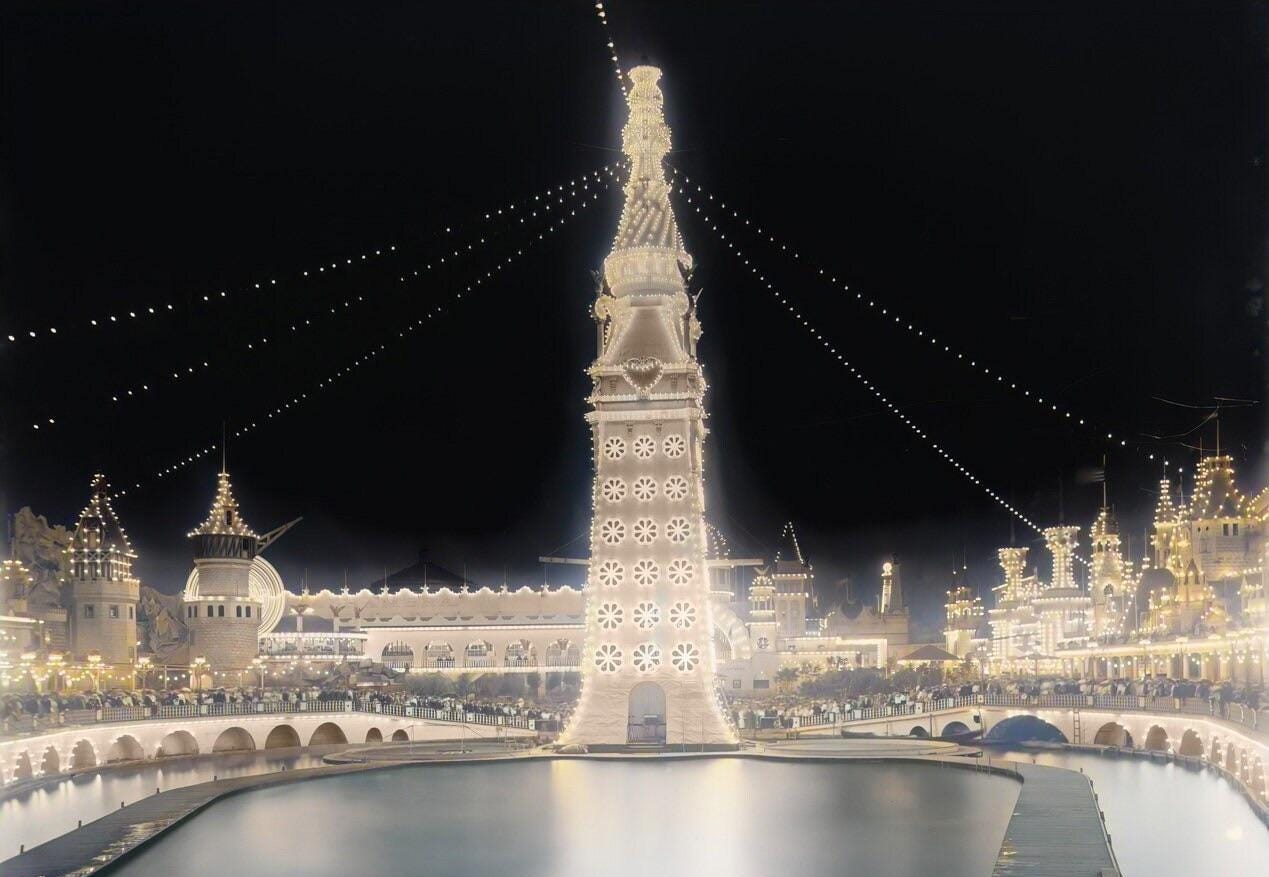

He lived with his parents in a rent-controlled apartment in Luna Park; a housing project that got its name from the old amusement park that once electrified the Coney Island skyline with a quarter of a million lights.

But the 20-story housing projects that took its place were orange, brutalist slabs, encased in rusting chain-link. This would be my next home.

Kosher Kowboy

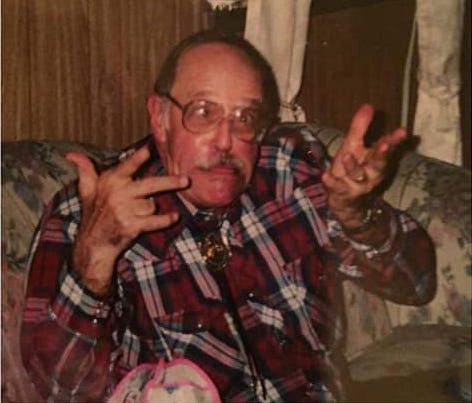

Of course my new father also came with another potential male role model, my grandfather.

My new grandfather was a real character, and a delight. He dressed like a cowboy, was a retired science teacher, and an amateur stand-up comedian. Every time I saw him, he had a new set of material for me, much of it wildly inappropriate for kids.

He called himself the Kosher Kowboy, because he was Jewish and was stationed in San Antonio when in the US Army.

As all dads do, Kowboy and his son used puns and goofy wordplay ala George Carlin. Kowboy was also inspired by the Jewish comedians of the New York Catskills (the "Borscht Belt"): who used quick, deflective humor, usually aimed at their wives. This may have played a role in his double divorce (to the same woman).

Just like my stepdad, his “best” jokes (the stuff he had to get close and tell you quietly) often featured taboo views on sex and race, told in the rebellious spirit of Jewish comedians like Lenny Bruce or Andrew Dice Clay.

That same sense of humor would eventually pass on to me—a non-genetically inherited trait impressed through nurture.

Selling Sausages?

One of the first jokes I remember my Dad telling me was one that is distinctly a joke among males.

It’s simply one line (the punchline): “You selling hot dogs?”

The rest of the joke runs in reverse; you look at their face to try to understand the question and notice they are looking down or gesturing to your lower body.

Then you look down and discover your fly was left unzipped. YOU are the joke.

Another twist: the joker is also the audience, because now they get to revel in your embarrassment as you fumble to hide your shame.

I remember not understanding the joke at first. Seemed like a simple mistake. His reaction made me realize, I should feel shame about this. The next time it happens, the embarrassment and need to correct the mistake will be stronger.

After he retired, my grandfather spent countless hours scanning the Coney Island beach with his metal detector, searching for diamonds and gold like Sir Raleigh searching for El Dorado. His house was full of found rings and thousands of tarnished nickels most of which have since been returned to the land.

Though I spent many years of my childhood here, I wouldn’t realize how important Coney Island was to American history until I was much older. It was known as the end of the world but it was also the beginning of a new chapter in American History, one that we are still in.

The Nickel Empire

Long before Times Square, Coney Island taught New York how to sell a fantasy.

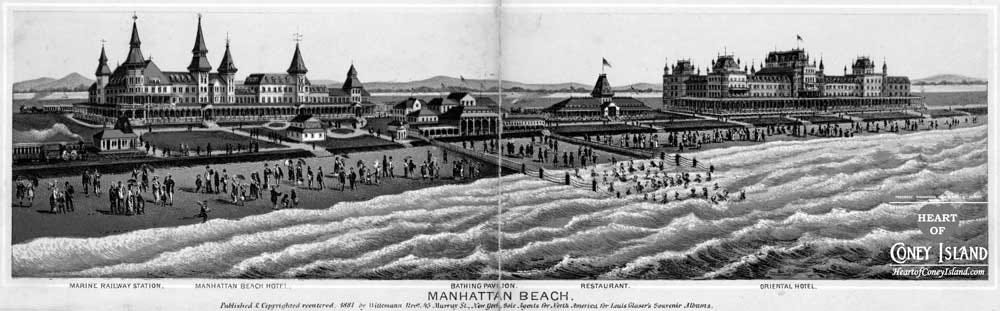

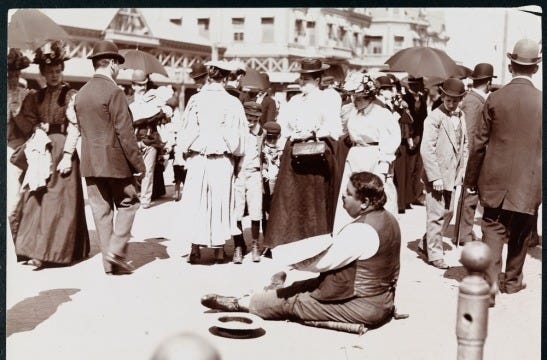

From its earliest days, Coney Island was a place of hustles, cheap thrills, and grand illusions. Before the 1870s, Coney Island was a place for picnics and nature walks. By the mid-century, with the introduction of ferry service from Manhattan , it began to develop as a more commercialized resort, bringing large numbers of visitors. There were plans to turn Manhattan Beach into an elite resort that would ban Jewish immigrants.

New roads connected the otherwise remote destination to the mainland, attracting slews of new European immigrants who had just begun arriving in droves. It became known for its vibrant, often gritty atmosphere, with a mix of upscale resorts, working-class entertainment, and a diverse range of attractions.

The 200-foot Elephant Hotel had become a brothel before it burned down in a spectacular fire that was visible from Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

In the 1870s and 1880s, amusement rides (such as the first roller coaster) began to appear in Coney Island, drawing more crowds seeking thrills and spectacle.

Dubbed “America’s Playground,” Coney Island was America in miniature; a cultural space that embodied both the excitement of modernity and the tensions of class, race, and entertainment in the emerging American industrial era. A place where dreams were mass-produced, sold for a nickel, and already falling apart by the time you reached the exit.

Coney Island had also become a testbed for emerging technologies. The Kinetoscope (Edison’s invention for viewing short films individually through a peephole) was a featured attraction in many arcades and sideshow parlors.

These machines were coin-operated and deliberately voyeuristic, reinforcing Coney Island’s broader cultural role as a place of social inversion: where working-class men could briefly feel wealthy, and social norms could be bent under the mask of amusement.

Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1894) and Fatima’s Dance (1985), were among the most widely distributed Edison films at the time.

Side Quest: Dance Like An Egyptian

Before Marilyn. Before Madonna. Before TikTok. There was Annabelle Whitford Moore: the teenage dancer who lit up the earliest films.

She was 14 when she was invited to dance at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In 1894, she starred in “Annabelle Butterfly Dance”, filmed using Edison’s Kinetograph.

Annabelle represented the genteel fantasy, a white girl spinning in silk, captured by Edison’s lens for coin-fed voyeurs. From 1896 to 1902, she was Annabelle Moore, Edison’s in-house muse at Edison’s The Black Maria, the first “film” studio.

Little Egypt

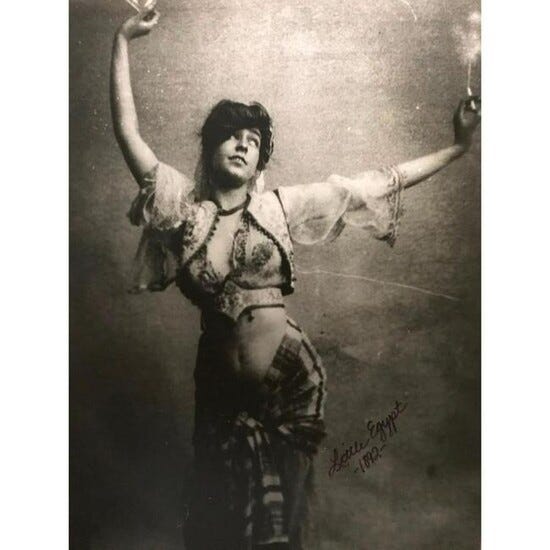

Also at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, a dancer billed as Little Egypt debuted the "hoochie coochie", an undulating, pelvic dance rooted in Middle Eastern traditions but repackaged as exotic titillation for white American crowds.

Her movements (centered on the hips, not the face) were unlike anything Victorian America had seen. A story circulated that Mark Twain nearly had a heart attack watching her, a myth that captured how deeply her performance rattled the American psyche.

Not long after, an Edison short film known as “Fatima, the Belly Dancer” featured the same dance but starring Fatima Djamile. She would also be associated with Little Egypt.

Fatima’s Dance became a scandal and a hit. Edison’s team later re-cut the film to cover or remove the most revealing moments, marking one of the first acts of cinematic censorship.

The Greatest Bachelor Party on Earth

As this New York Journal article from 1897 describes, in December 1896, Annabelle Moore was invited to perform, semi-nude, at an elite Gilded Age Bachelor Party for Clinton Seeley, grandson of P.T. Barnum. She refused. Her stepfather reported the party to the police, prompting a late-night raid. No charges were filed, but the scandal was public.

Another Little Egypt (Ashea Wabe) is said to have stepped in to perform instead (hiding in the closet when police checked in) eventually delivering the spectacle the men wanted.

Little Egypt also became a national obsession, triggering waves of moral panic and legal crackdowns, but also voyeuristic curiosity. For middle-class white Protestant audiences, Little Egypt was a culture shock. Her dance challenged ideals of female purity, decorum, and racial superiority, even as it was consumed with morbid fascination.

Wanna Have Some Fun?

Steeplechase Park, the first great “amusement” park, opened in 1897. It was a mechanized playground where the working class could laugh, collide, and blush in public.

Steeplechase revolved around bodily humor and class inversion—funhouse mirrors, mechanical horses, spinning barrels, and sudden gusts that lifted women’s skirts. Kosher Kowboy’s father was one of the men who operated the blowers.

Observation galleries and elevated walkways allowed non-participants (often from higher social strata) to watch the chaos below, laughing at the poor, the foreign, the unrefined as they stumbled, shrieked, and exposed themselves, physically and socially.

It was a park of orchestrated humiliation, where elites and laborers alike could stumble together, watched over by the iconic grinning face that promised permission to lose dignity without consequence. This wasn’t just amusement, it was ritualized release, carnival with gears.

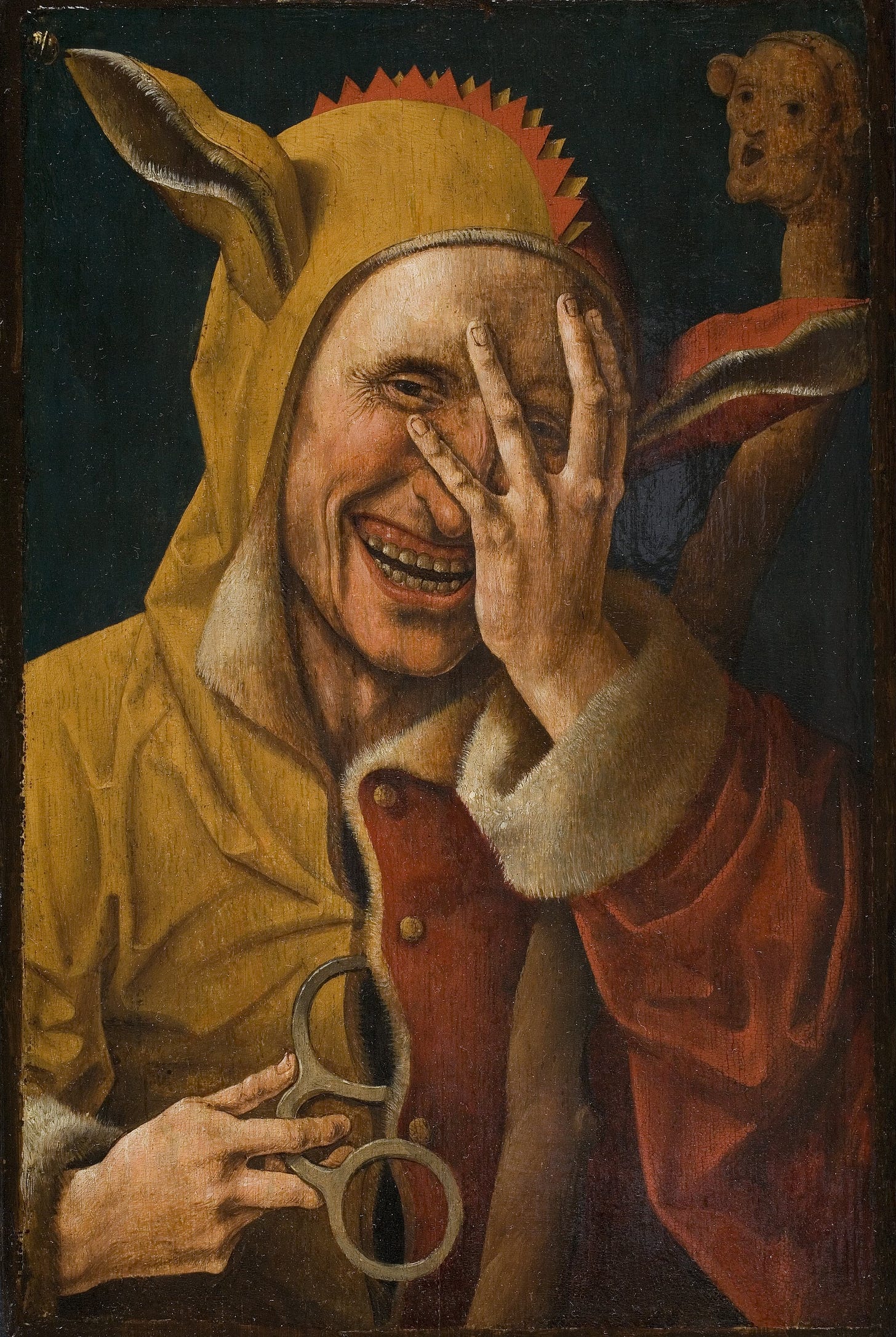

The Steeplechase Funny Face was part of a long tradition that stretched back through Victorian satire, circus posters, medieval carnival culture.

Epic Side Quest: Why So Serious?

Comedy began as part of religious festivals honoring Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ecstatic celebration.

Dionysus represented duality: god and beast, liberator and destroyer. A liberatory impulse, the joy of release, and the sacredness of laughter.

The word “comedy” (komoidia) means “song of the revelers.” Early performances combined choral songs (komos), phallus processions, and improvised mockery of public figures.

Participants would parade through the city carrying giant phalluses, wearing masks, animal skins, and grotesque costumes.

Dionysus was also the god of theatre itself. The Aristophanes, the grotesque faces, oversized mouths, and phallic symbols still echoed the primal chaos of the god.

The Father of LOLs

Before comedians interviewed billionaires and jesters whispered to kings, there was Aristophanes, aka The Father of Comedy.

In Aristophanes’ The Knights (424 BC), two foolish slaves (named after real generals) serve a senile master (the Athenian people). They’re terrified of another slave the Paphlagonian (a stand-in for the real life merchant-turned-politician and demagogue Cleon) who has manipulated their master through flattery and lies.

Unable to stop him themselves, the foolish slaves recruit a clever, lowborn sausage seller, who uses wits, vulgarity, and shamelessness to outdo the demagogue at his own game.

By the time of New Comedy (Menander), slaves became key comedic characters, their masks emphasizing low status: snub noses, wide mouths, and bewildered or menacing expressions.

The Romans, borrowing heavily from Greek New Comedy, further formalized the theatrical mask. The Clever slave (servus callidus), often the smartest in the play, was ironic considering the mask still conveyed low status. He often pretended to be foolish.

Sausage Fest

Once known as Saturnalia and the Feast of Fools, Carnival: was a time when anonymity reigned, social ranks dissolved, and appetites ruled.

In medieval and Renaissance European carnivals, sausages frequently appeared in farces and parades as symbols of male sexuality.

The Feast of the Circumcision of Christ was celebrated on January 1st in the medieval Christian world. This feast marked the ritual circumcision of the infant Jesus (eight days after his birth, per Jewish custom).

The foreskin is rich in nerve endings and protects the sensitivity of the glans. Removing it reduces friction, desensitizes the penis over time, and lowers sexual intensity.

The sausage (especially in the context of satire, Carnival, and politics) is the comic inversion of circumcision. The foreskin is often seen, in mystical and moral terms, as a symbol of unregulated male pleasure.

In this strange overlap, ritual purification and social inversion were mirrored: as the sacred body was marked, the public body (through Carnival) was unbound.

Who’s Laughing Now?

Carnival in Venice gradually expanded into a six-week season of masked revelry, beginning in late December and culminating on Martedì Grasso (Fat Tuesday).

For six weeks, the city turned itself inside out. All sins were permitted, so long as you wore a mask.

The Venetian Republic had institutionalized Carnival as a tool of soft control.

Mikhail Bakhtin called this the carnivalesque a “cultural safety valve”, where the pressures of hierarchy, repression, and propriety were released not through revolt, but through revelry.

Nobles dressed as beggars. Courtesans posed as monks. The powerful became fools, and the fools were suddenly kings.

Pro Fools

The Artificial Fool was a licensed truth-teller—an educated or quick-witted performer skilled in satire, mimicry, music, and wordplay. He used exaggerated speech and theatricality to mock power and entertain the elite, often speaking truths others could not.

In contrast, the Natural Fool was not a performer but a mentally disabled person seen as “touched by God.” Kept for amusement, affection, or pity, the Natural Fool hovered between pet and mascot (sometimes cherished, sometimes exploited).

He functioned as both pressure valve and mirror, reflecting the king’s image with humor, offering insight without accusation.

The King of Fools

In 1514, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I gifted a bizarre piece of armor to King Henry VIII: a helmet with a leering human face, grinning mouth, stubbled chin, and spiraling horns, topped off with a pair of riveted spectacles.

Some scholars suggest this gift was layered with a subtle mockery. The lewd, carnivalesque features might have referenced the theatrical “fool” or cuckold—dangerous ground, considering Henry’s well-known pride.

Much like the artificial and natural fools, the Knave (an early Jack playing card) is associated with upper and lower trades. The lower knave or natural fool is hold a holding a sausage, which implies gluttony or lust.

Given that the helmet came two years after the breakdown of Maximilian and Henry’s alliance against France, it’s plausible to see it as a jab masked as a gift. But the lower knave was also a trickster, so there may have been layers to the message.

Foolish Pride

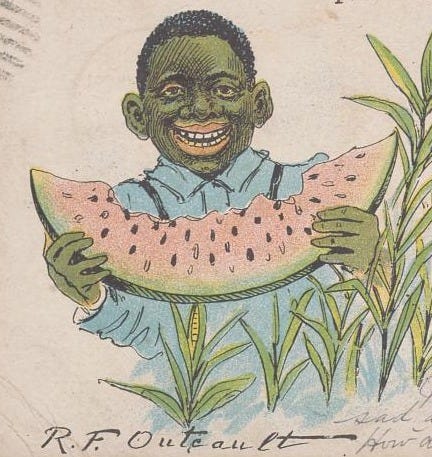

The Supreme Court’s 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson had upheld “separate but equal,” legalizing Jim Crow segregation nationwide. The smiling comic mask returned once again.

Jim Crow (Natural Fool): the rural, slow-witted plantation fool, born of cruelty and nostalgia.

Zip Coon (Trickster Fool): the slick-talking, overdressed urban “dandy” who mangled the King’s English and believed himself equal to white men, a joke built on the misplaced confidence of a Black man.

The audience laughed not with him, but at the idea that he might rise. His smile wasn’t seen as joy, it was viewed as containment.

The smile, in this tradition, became a trap. A symbol of supposed contentment in the face of oppression.

A demand from the powerful: show me you’re not angry.

No Laughing Matter

In Victor Hugo’s novel The Man Who Laughs (1868), the central figure, nobleman Gwynplaine, is disfigured as a child (his mouth carved into a permanent grotesque grin) and literally turned into a freak show attraction.

Despite his kindness and noble spirit, society rejects him, seeing only the mask. Hugo’s grim message is clear; in a world built on cruelty and spectacle, the true tragedy isn’t just suffering, but the certainty that suffering will be misunderstood, or worse, ignored.

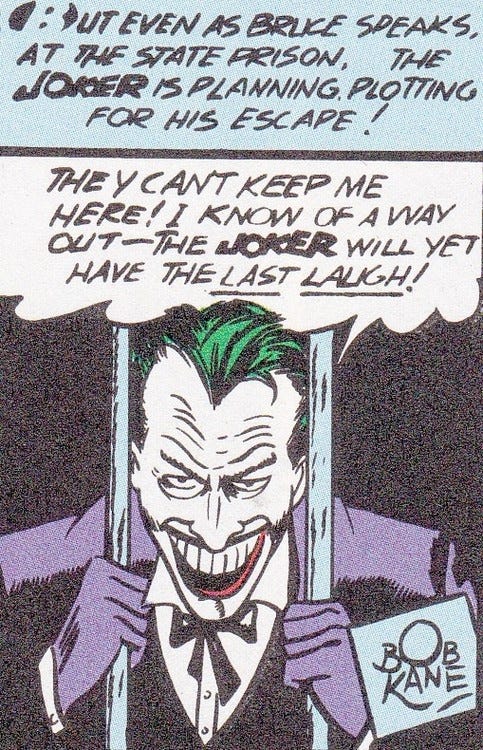

The Last Laugh

When the Joker first appeared in Batman #1 (1940), he was modeled after Conrad Veidt’s silent performance as Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs (1928).

But in American mythology, the Joker fused with carnival violence, vaudeville cruelty, and postwar cynicism. He became the clown who laughs not because he’s happy, but because nothing matters. He is the Steeplechase Face unleashed: unkempt, blushing, wide-eyed, and grinning at collapse.

Why Worry?

As Irish Americans gained political power in the early 1900s (especially through Tammany Hall) an image evolved of a simple country bumpkin with an unruly smile, like the blackface grin, his was a mask of containment: this man won’t rise, he’s too stupid to know he’s oppressed.

By the 1930s, New Deal opponents revived the "gullible Irish sap" to mock FDR voters: smiling idiots manipulated by machines of power they couldn’t understand.

And in one of American satire’s most perverse inheritances, this archetype survived yet again, repackaged as the freckled, grinning, red-haired mascot of MAD Magazine: Alfred E. Neuman. With his slogan: “What, me worry?”

In his memoir The Quest for Alfred E. Neuman, chemist and writer Carl Djerassi reflects on the unsettling familiarity of MAD Magazine’s iconic mascot.

As a Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Vienna, Djerassi had seen a nearly identical caricature on anti-Semitic propaganda posters—same ears, same grin, same grotesque features.

Smile

Smile, composed by Charlie Chaplin for his film Modern Times (1936), became an anthem of resilience in a decade scarred by the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and the rise of fascism.

Chaplin’s “Little Tramp” character (dusty suit, cane, bowler hat) was more than a slapstick icon. He was a working-class everyman, a migrant, a drifter, a survivor of the machine.

At a time when Hollywood studios were still dancing around Nazi Germany, Chaplin (half-Jewish, poor, immigrant) took direct aim.

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI opened a file. Chaplin was investigated for communist sympathies, accused of immoral behavior, and eventually exiled.

Have A Nice Day!!

The smiley face, created in 1963 by Harvey Ball for an insurance company, was meant to pacify anxious workers after a merger. It was a corporate tool to mask discontent.

Later commercialized with the phrase “Have a Nice Day,” the smiley became a symbol of enforced positivity; now a demand, not a sentiment.

Electric Eden

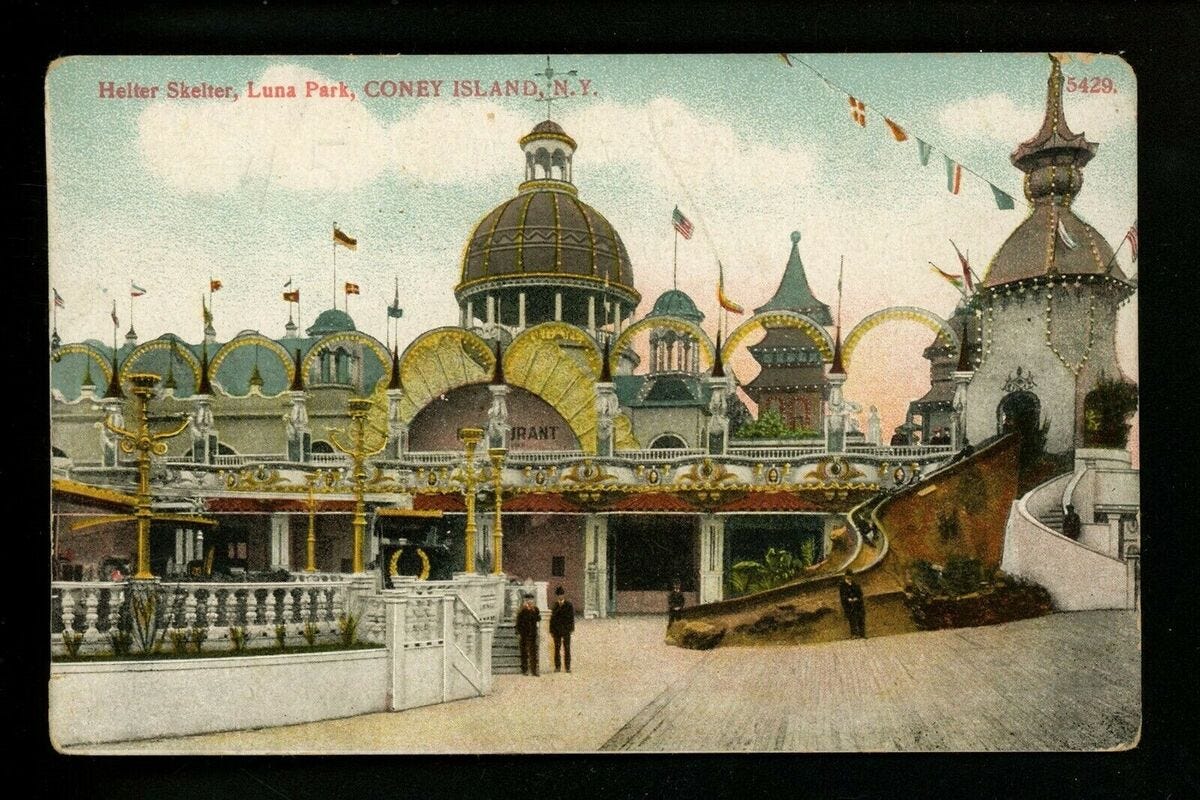

Luna Park began as a hallucination brought to life: a glowing playground of electricity, fantasy, and mechanical wonder that emerged seemingly overnight in 1903.

Luna Park, co-founded by Frederic Thompson, who had debuted his Trip to the Moon ride at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, carried over that exact attraction—complete with papier-mâché moonscapes and costumed Martians.

In a Coney Island still crawling out of its reputation as a rough-and-tumble beachside vice zone, Luna was something else. Not just a park, but a vision.

Named after both the moon and the myth of lunacy, the park invited visitors into a world of controlled chaos: glowing towers, mechanical rescues, fire rides, exotic villages, and dreamlike simulations.

In contrast to the orderly modern city, Luna offered a gleeful inversion—an escape from rational time, industrial labor, and moral restraint. Here, you could float through Martian landscapes, witness staged disasters, or lose yourself in light and noise.

To keep the crowds returning, founders Thompson and Dundy had to outdo themselves year after year. Every season brought new spectacles, each more elaborate and costly than the last.

As the novelty wore thin and copycat parks like Dreamland rose across the street, Luna had to spend more to deliver less. The margins got tighter, the stakes higher.

Living The Dream

Dreamland, opened in 1904, was one of the most ambitious amusement parks ever built, meant to rival Luna Park and turn Coney Island into a global entertainment epicenter.

Founded by former politician and real estate mogul William H. Reynolds, Dreamland’s architecture gleamed white with classical symmetry. Its attractions included a biblical Genesis diorama “Creation”, a re-staging of Pompeii’s destruction, and a literal End of the World show, complete with planetary apocalypse and salvific Christian cross.

This wasn’t just about who had the tallest tower or the brightest lights. Luna Park’s chaos was exuberant, childish. Dreamland's was clinical, adult. One offered escape. The other promised salvation, for three nickels a head.

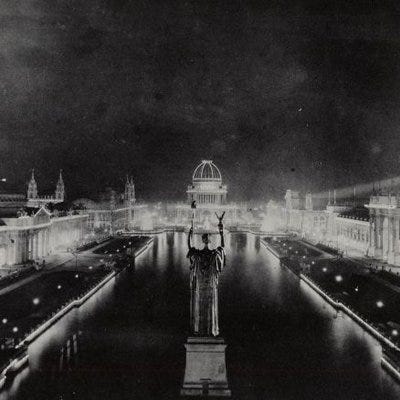

Luna Park and Dreamland were direct descendants of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, borrowing not only its architectural style but also its ideological framework and core attractions.

Modeled after the White City’s gleaming façades, both parks used plaster, staff, and electric lighting to create a dazzling dreamscape of modernity, fantasy, and order—designed more for nighttime spectacle than permanence.

The stucco was also not weather-resistant and highly flammable.

Side Quest: The White City

The Chicago World's Fair of 1893 was a technological wonder, best remembered for Thomas Edison's luminous "White City," illuminating not just buildings but America's collective imagination.

It was a sprawling, neoclassical collection of white stucco buildings that were designed to impress and symbolize America's entry into the modern age.

The buildings were made from a temporary material called staff, a mixture of plaster and burlap, which gave them the gleaming white appearance that inspired the "White City" nickname. These buildings were not meant to be permanent; rather, they were constructed as part of the spectacle of the fair, showcasing American architectural and engineering prowess.

Here, electricity wasn't merely displayed, it was mythologized as the engine of future progress. The White City was more than just a display of technological advancement; it embodied an ideology of order, purity, and control.

Its gleaming white buildings symbolized the triumph of American industrial power, reinforcing the idea that progress required cultural and racial supremacy.

Human Zoo

The Ethnological Exposition was a section of the fair where people from various non-Western cultures were put on display in what were essentially "human zoos."

The ethnic villages of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 were intended to showcase "primitive" peoples from around the world, such as Native Americans, African tribes, Filipinos, and Eskimos, often in re-creations of their supposed native habitats. The fair organizers, influenced by ideas of Social Darwinism and racial hierarchies, presented these people as living examples of early stages of human evolution, placed in contrast to the so-called "civilized" white attendees.

The activities performed by the people displayed at the Ethnological Exposition of the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 were not always an accurate representation of their actual cultures at the time.

Many of these individuals were asked to perform or reenact “primitive” or archaic practices that aligned with the fair's goal of presenting them as living examples of early human stages, reinforcing racial and cultural stereotypes. In many cases, the performances were exaggerated, romanticized, or invented for the amusement of fairgoers.

Over 20 million people reportedly visited the fair in it’s 6-month run before the temporary stucco buildings began to crack and deteriorate. While the majority of the buildings were torn down, the fair's ideals and innovations lived on. Elements like Edison’s electric lighting and early amusement park rides were incorporated into future attractions, notably in Coney Island.

Greeks & Freaks

At the heart of Dreamland’s spectacle was the Freak Show, both literal and metaphorical. The park featured a dedicated sideshow of “living curiosities”—bearded ladies, giants, dwarfs, conjoined twins but also what might be called ideological freakery: the infantilized poor, racial “others,” and disabled veterans presented as objects of fascination and pity.

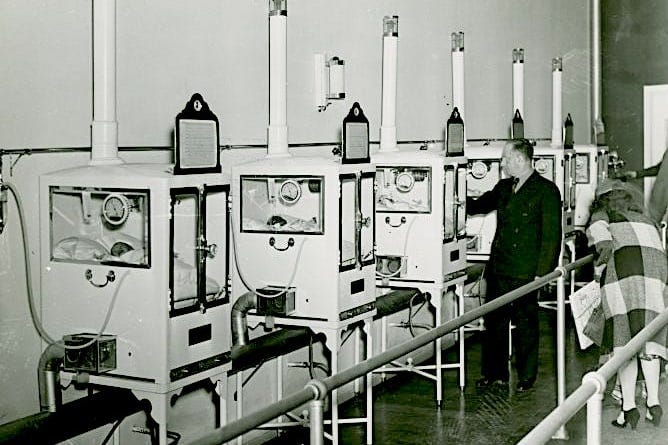

Alongside these were artificial disasters like the “Hell Gate” fire reenactment and the “Infant Incubator” exhibit, which presented premature babies as both marvels of science and living sideshow attractions.

These juxtapositions (between life and death, technology and deformity, progress and perversion ) were not accidental. They were the essence of Dreamland’s vision.

Whereas Luna Park leaned into fantasy and electricity, Dreamland tried to moralize its spectacle. It showcased “Lilliputia,” a miniature city inhabited by little people, and staged dramatizations of prison life and ethnic “exhibits” like “Zulu warriors” and “Aztec children.”

Taming The Wild Man

One of the most striking figures of the Coney Island freak show era was Chief Pantagal. Marketed as a “South Seas Islander” or “native of New Guinea,” Chief Pantagal was presented to audiences as a living artifact of colonial fantasy; bare-chested, adorned with feathers and beads, and posed to evoke the image of a “primitive” warrior or wild man.

Chief Pantagal, known in the sideshow circuit by that stage name, was in fact Thomas Robinson, a performer who worked with traveling shows and eventually at Coney Island’s World’s Circus Side-Show. A 1920s article from The Billboard reveals that Robinson was arrested in Frederick, Maryland after a shooting incident in which he claimed self-defense.

The case ended with only a one-dollar fine, and his release was aided by local allies and show business contacts. Far from the “South Seas native” persona constructed for audiences, Robinson was a savvy showman navigating both legal trouble and the economics of sideshow life.

The Main Distraction

In the summer of 1905, fifty members of the Bontoc Igorrote tribe from the northern Philippines were transported to Coney Island by an American showman named Truman Hunt, who promised them $15 a month and a chance to perform a “tribal show.”

Instead, they were confined to a fabricated village, forced to reenact rituals—including dog-eating (an otherwise rare meal in their culture) for millions of paying spectators. Hunt built a fake headhunter’s watchtower and marketed them as savages, feeding a national fantasy that framed American imperialism in the Philippines as benevolent uplift.

Though the U.S. had seized the Philippines in 1898 under the guise of bringing “civilization,” cities like Manila already had printing presses, universities, and European-educated elites. Most Filipinos were Catholics, farmers, and artisans—not tribal nomads. By showcasing only remote hill tribes, American showmen erased this reality to justify conquest and extraction.

The press sensationalized their bodies and customs. Hunt withheld their pay, fed them dogs from the city pound, and fled across state lines when investigated, pursued by Pinkerton agents. The audience saw spectacle; what they didn’t see was exploitation disguised as entertainment.

Side Quest: Eugenicists At The Freak Show

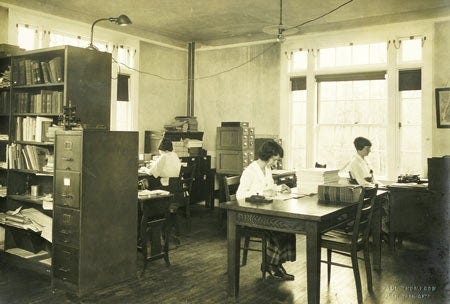

From 1910 the brand new Eugenics Record Office operated out of Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, collecting family pedigrees and advocating sterilization of the unfit. 85% of the people working at these offices were women.

Between 1910 and 1935, Long Island-based eugenicists visited sideshows in Coney Island to observe, catalog, and classify the “abnormal” bodies on display. Not just the dwarfs, conjoined twins, bearded ladies, tattooed performers, but also crowd behavior and public spaces as sites of “degeneration” and social threat.

Figures like Chief Pantagal were documented for their racial features, family pedigrees, and supposed degeneracy.

Meanwhile, performers like Little Egypt, a sensation by 1915, drew crowds with eroticized “Oriental” dances that reinforced colonial fantasies and racialized sexuality.

Coney Island (especially during the Dreamland era) represented everything that eugenics wanted to control: racial mixing, sexual freedom, urban anonymity, and the visual normalization of “abnormal” bodies.

It was a living laboratory of immigration-era anxiety. Italian, Irish, Jewish, Caribbean, and Eastern European visitors mingled freely with each other and with WASP elites slumming it for cheap thrills. Eugenicists saw this as a threat to both racial purity and social order.

Coney Island was viewed as a site of moral, racial, and biological risk.

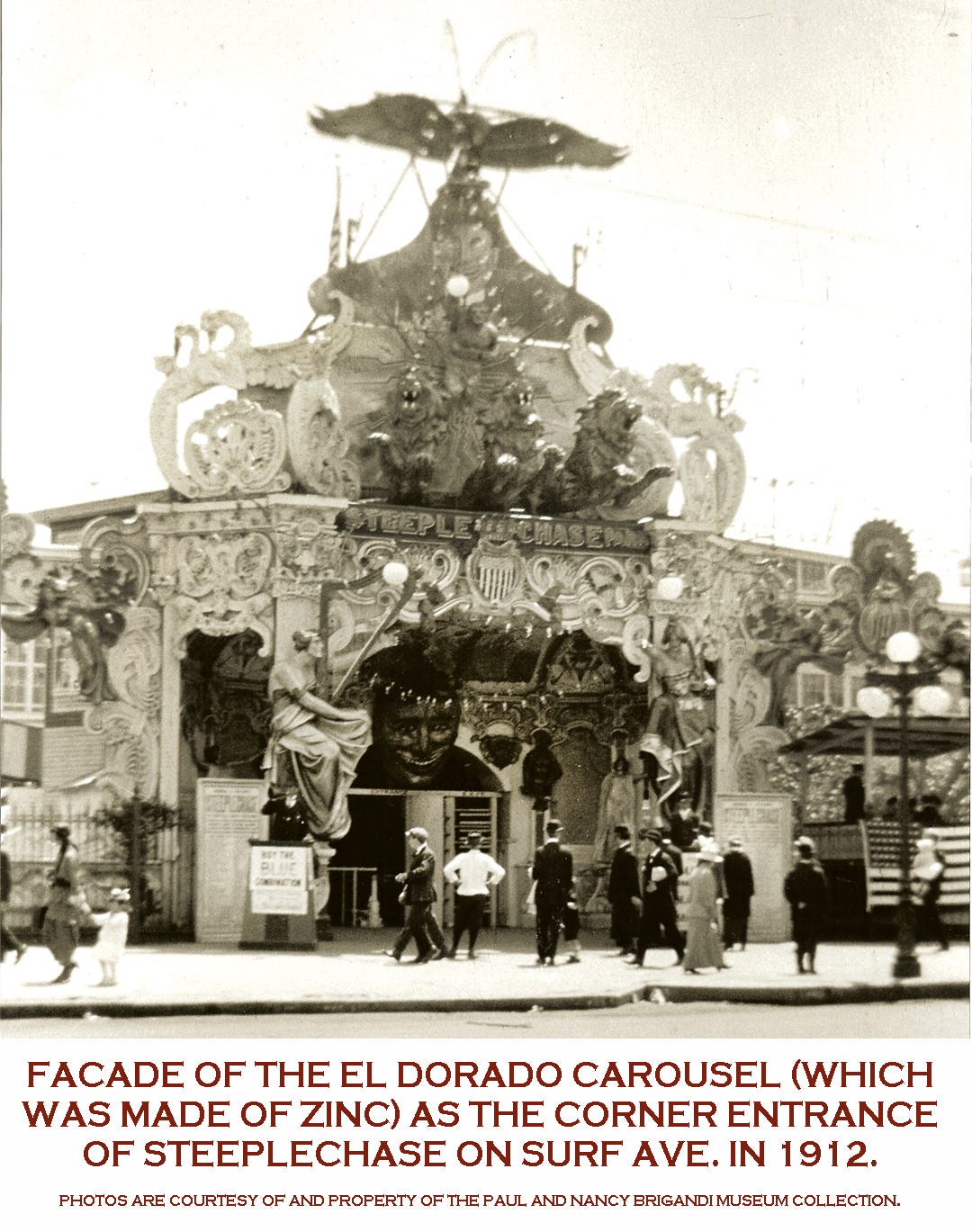

Side Quest: El Dorado Carousel

Crafted in 1902 by German carousel maker Hugo Haase, the El Dorado Carousel was a marvel of its time. Featuring three platforms rotating at varying speeds and illuminated by 5,000 lights, it captivated visitors with its grandeur.

After surviving the 1911 Dreamland fire, albeit with some damage, it was relocated to Steeplechase Park's Pavilion of Fun in 1912.

Subsequently, it was sold and eventually found a new home at Toshimaen Amusement Park in Tokyo, Japan. Today, it stands as one of the oldest operating carousels in the world.

Sodom By The Sea

By 1910, Reynolds admitted Dreamland never paid investors or serviced its debt.

Dreamland’s debts totaled $2.2 million, and Reynolds hoped to recover money via land sales rather than park operations. He even attempted to sell the park back to New York City at a rigged markup, masking a failed entertainment venture as a civic gift.

Thompson died suddenly in 1911, just weeks after Dreamland burned to the ground while work was being done on the Hell Gate. Dreamland’s internal fire system failed. The fire gutted the park within hours, killing animals, destroying attractions, and rendering most of Dreamland unsalvageable.

After Dreamland burned in 1911, Luna briefly thrived, but without co-founder Frederic Thompson’s visionary leadership, it slid into creative stagnation. The 1920s brought competition from newer, more thrilling attractions, while the Great Depression in the 1930s drained audiences and left the park crumbling.

In 1930, Sodom by the Sea exposed the underside of the dream. Oliver Pilat and Jo Ranson chronicled the crime, graft, and decay eating away at the fantasy.

Coney Island was rotting from the inside long before the crowds thinned. Businessmen cut corners. Politicians took bribes. Mobsters skimmed off the top. The parks that once promised wonder slowly crumbled into scams and firetraps. No one repaired. They drained every last dollar out of the dream, and when it finally collapsed, they blamed the immigrants and the poor. But the truth was simpler. The system had devoured itself.

By the 1940s, Luna had become a faded relic of a bygone era. Its end came on August 13, 1944, when a massive fire (fueled by decades-old wood and plaster) ripped through the park. It was never rebuilt.

Behind the lights and laughter was exploitation of labor and corruption. The same system that built Coney Island would burn it down without blinking. It was capitalism’s first carnival, and its first graveyard.

The most notorious section of Coney Island was called "The Gut", a knot of back alleys, crumbling houses, and storefronts patched together with hope and hustle. When the dream started dying, The Gut was what remained.

City officials often referred to it as one of the worst slums in America. It’s name was likely a shorting of gutter, but it must have felt like the belly of hell.

Side Quest: Fred Trump’s No Fun Zone

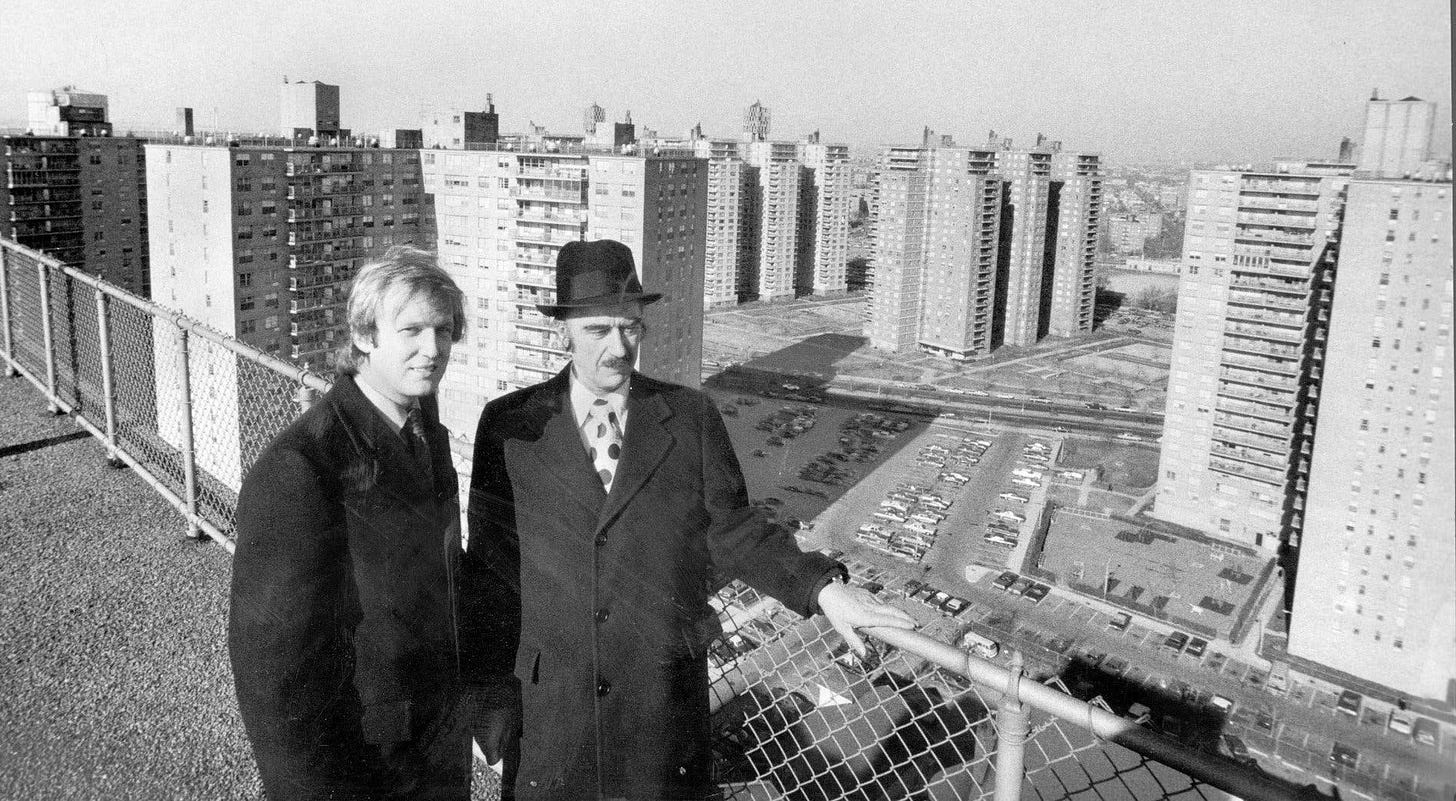

Fred Trump had acquired part of the old Luna Park site in the early 1950s. (Luna Park had already been destroyed by fire in 1944, so he was buying the vacant, charred land.)

But in the 1950s, Trump was blacklisted by the federal government (following investigations into profiteering and corrupt practices involving public housing contracts) and he lost the Luna Park land.

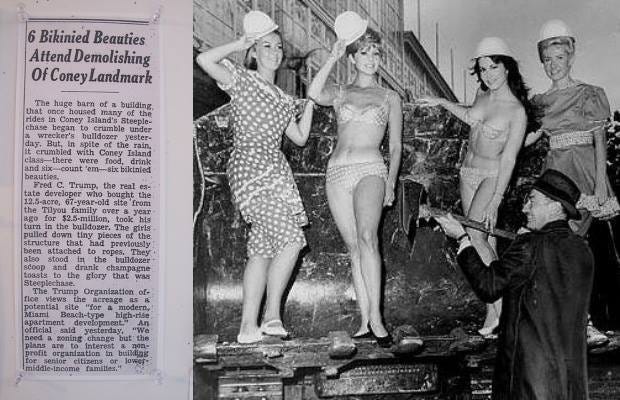

By the mid-1960s, preservationists were pushing to landmark parts of old Coney Island. Steeplechase Park (the beating heart of the dream) was under consideration. But Fred Trump had other plans.

He intended to redevelop the site, initially claiming he would bring in new amusements. But in reality, he wanted high-rise residential projects there too.

In the early 1960s, he built Trump Village nearby. To clear space, he pushed low-income families into dilapidated summer bungalows in Coney's West End and profited from the relocation fees paid by the government. But these communities had no winter insulation, no infrastructure. It was a poverty trap.

Fred Trump helped engineer the decline of Coney Island by displacing poor families. And he profited from it. Trump bought the land, threw a demolition party, handed out bricks, and bulldozed the Pavilion of Fun before the Landmarks Commission could act.

It wasn’t just demolition—it was humiliation. A public execution of the old American dream. Trump promised luxury condos but never built them. He left behind an open wound: rubble, rust, and chain-link fences.

Welcome, My Son

By 1986, I was living in Luna Park, sleeping on the couch in my soon-to-be stepdad’s family home. I don’t know if I missed my Guyanese family. Maybe I was too distracted with cartoons and candy.

I was eventually given their name, but not their culture. Judaism was their religion. But just like the Islam practiced by my Guyanese family, religion was mostly a meal shared on a holiday. My Jewish grandmother used Christmas-themed wrapping paper for my Hanukkah presents.

Nathan’s hot dogs are “Kosher-style” but technically not Kosher, not that it mattered to my stepdad. Judaism may have been their religion but Comedy was their spiritual practice. Making fun of you was their love language.

My stepfather and his father had something else in common: both suffered from depression, addiction, and were prone to fits of rage and sometimes violence.

But before the tears, anger, divorce, and silence—there was laughter.

Welcome To The Machine 3: The Muscle

This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.