This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

My new stepdad was also an amateur “bodybuilder”, which had become very popular in the 70s and 80s thanks to people like Arnold Schwarzenegger. I remember him watching and quoting Pumping Iron (1977), one of the first VHS tapes we owned.

He tried to get me into it weightlifting too, even took “before” pictures to catalog my transformation from scrawny weakling to… unknown. The “after” never came. I quickly lost interest and eventually so did he.

My grandfather, Kosher Kowboy, was also into physical fitness and was once a member of the Coney Island Polar Bear Club; a winter swimming club founded at the turn of the 20th century.

Every winter, club members would strip down and charge into the freezing Atlantic Ocean, believing it built vitality, masculinity, and character.

My grandfather quit the club in 1984 when, after swimming in below freezing temperatures, he noticed his white fingertips and worried his manhood might be permanently disabled from the cold. That was also the year an elderly member of the club died while in the freezing water.

The Coney Island Polar Bear Club was founded in 1903 by a man known as “The Father of Physical Culture,” a highly controversial but influential health guru and multi-millionaire publisher who has all been erased from history.

He taught Charles Atlas.

His writings also deeply inspired the Kennedy family.

He also helped promote the early ideas of Eugenicists.

He was just a symptom of an age of men who were obsessed with might and purity, but also deeply insecure about their changing status in the world.

Buckle up, bitches.

Body Love

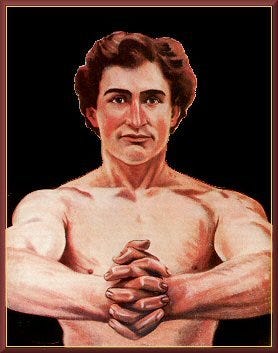

Before the gyms and protein powders, before Charles Atlas and Jack LaLanne, before Joe Rogan and Wim Hof, there was Bernarr Macfadden.

On New Years Day, 1904 in Coney Island, Macfadden led a group of followers into the icy Atlantic Ocean as a public demonstration of health, discipline, and “nerve force.” He was mostly there to promote his magazine “Physical Culture.”

Bernarr (who changed his name from Bernard because it sounded like a lion’s roar) was also known in tabloids as “Body Love.”

Born in 1868 and orphaned young, Macfadden was a sickly child who claims to have nursed himself into top physical condition thanks to a regimen of vigorous exercise and lifestyle choices.

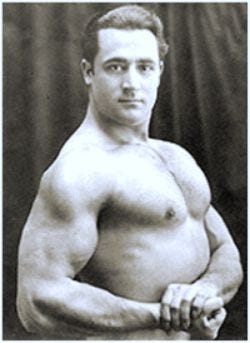

In 1893, Bernarr Macfadden (then still Bernard McFadden) visited the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He was 25, recently transformed from a sickly orphan into a fitness-obsessed crusader. At the fair, he saw Eugen Sandow posing under electric lights. For Macfadden, it was a revelation.

He wasn’t drawn to the art or the architecture. He saw the future in muscle, discipline, and spectacle. Sandow’s body wasn’t just impressive, it was proof that physical perfection could be a system, a message, a business.

Within a few years, Macfadden had changed his name and launched Physical Culture magazine in 1899.

Side Mission: The Mold

In the last essay I mentioned the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and Edison’s early films of Annabelle and Fatima. There was another figure captured by Edison’s camera. Not dancing, but posing, nearly nude. Sandow (1894) is also one of the first films ever made. Edison believed Sandow represented the “perfect male form.”

Eugenic

Friedrich Wilhelm Müller was born in Prussia where he performed as a strongman under the name Eugen Sandow. Unlike the common name “Müller”, Sandow may have held a more noble Germanic tone.

“Eugen” (from Greek eugenēs) in German means noble-born, of good stock.

Only A decade earlier Francis Galton used the same root to coin the term “eugenics” which he defined as:

“The science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.”

Sandow was not “Nordic” in the racial sense later defined by eugenicists like Madison Grant, but he became the visual archetype that those ideologues elevated: pale, symmetrical, classically proportioned, and morally disciplined.Sandow modeled his body on classical Greek statuary; specifically the Farnese Hercules, which he studied and measured to replicate in proportion.

He promoted physical development as a moral, aesthetic, and civic duty, and through touring exhibitions, published guides, and entrepreneurial savvy, he became the first global fitness celebrity.

In the decades that followed, fascist aesthetics, fitness cults, and body politics across Europe would draw from this mold.

The Return of The Olympian

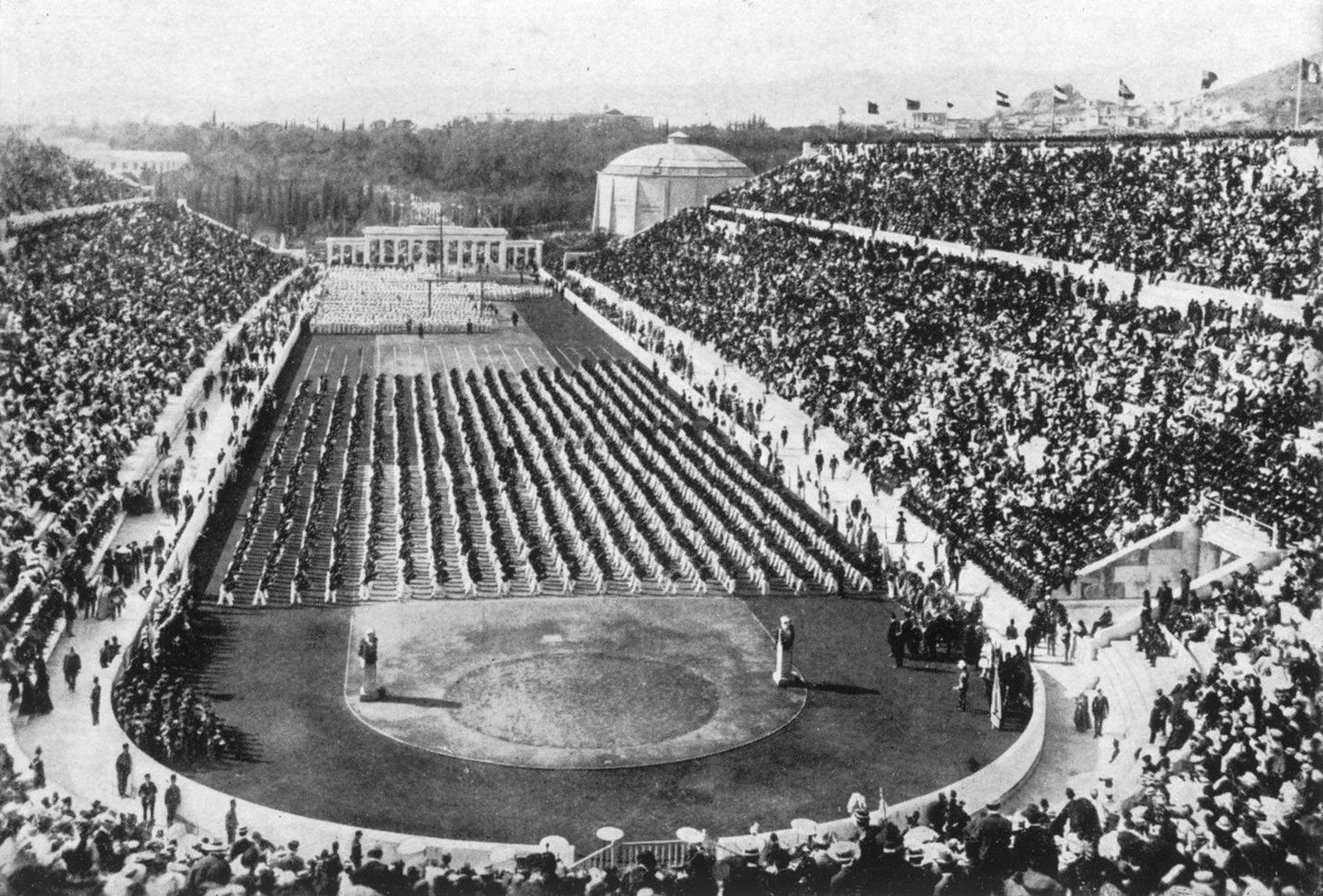

It’s common assumption that the Olympics have been around since the days of ancient Greece. But the games were deemed a pagan festival and banned in 393 CE.

The Olympics were resurrected in the 20th century thanks to Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat who was inspired in part by Sandow. He saw in the ancient games a way to restore harmony between body and mind, and to channel masculine energy into disciplined competition.Coubertin launched the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894. The first modern Games were held in Athens in 1896, with 14 nations competing. Nearly all athletes were white Europeans or white Americans. No athletes from Africa, Asia, or the colonized Global South competed.

Sandow served as the official “judge of the athletes” at the Olympic weightlifting competition (Germany won).In 1897, he opened the Sandow Institute of Physical Culture in London, the world’s first commercial gym chain, complete with instructors, medical consultations, and tailored programs for men and women. His goal was to make strength a science, to normalize the gym the way doctors normalized hygiene.

Body of the Empire

King Edward VII appointed Sandow as Professor of Scientific and Physical Culture. After the Boer War (1899–1902) revealed that a large percentage of British military recruits were physically unfit.

The ruling class feared that modern life (factory labor, urban decay, moral softness) was producing a generation of degenerate men.

Enter Eugen Sandow, the embodiment of classical perfection.

In 1904, Sandow toured colonial South Africa, bringing his brand of physical culture to the imperial frontier. His body (lit and powdered to emphasize whiteness) became a spectacle of empire, a “scientific” model of the ideal Englishman.

By the 1910s, his influence began to fade. World War I changed the public relationship to strength and sacrifice. Men were conscripted, not trained. War demanded obedience, not symmetry.

By the time of his death in 1925, most of his gyms had closed or changed hands. His name, once synonymous with physical culture, was gradually forgotten, until the bodybuilding world resurrected it decades later with the Mr. Olympia “Sandow” trophy.

Fiscal Culture

In 1897, Macfadden traveled to England and partnered with bicycle entrepreneur Hopton Hadley to sell his wall-mounted muscle developer. With Hadley’s backing, he launched his first magazine, Physical Development (1898), followed by the far more successful Physical Culture (1899) after returning to the U.S. That magazine became the cornerstone of a fitness media empire, a mix of evangelism, spectacle, and pseudoscience.

Macfadden wrote 100 books about everything from health and beauty to womanhood and even fitness for babies. He preached about raw food, cold baths, sunbathing, barefoot walks, and sexual openness. He attacked alcohol, doctors, tea, coffee, corsets, white bread, and even mattresses.

Physical Culture also veered into quackery and extremism. Macfadden used its pages to rail against conventional medicine, denouncing doctors as enemies of true health to help promote his own eccentric regimens. He was staunchly anti-vaccine, blaming vaccines (rather than viruses) for sickness.

He invented devices to enlarge male genitals and marched to his Manhattan office barefoot carrying a 40-pound bag of sand. He also staged America’s first physique contest in 1903, laying the groundwork for bodybuilding culture.

The Perfect American Male

In 1903 Bernarr Macfadden organized what he called a “Physical Culture Exhibition”; an annual live event that featured posing competitions, strength demonstrations, and body evaluations.

These events were staged in major venues like Madison Square Garden and drew thousands of spectators. This would develop into the “Most Perfectly Developed Man” competitions, the first American bodybuilding competitions.

Macfadden personally oversaw the contest, which immigrant Angelo Siciliano won in 1921.

After winning, Siciliano eventually rebranded himself as “Charles Atlas” and launched the Dynamic Tension mail-order course in the late 1920s.

Alongside its uplifting messages, Physical Culture promoted a rigid and exclusionary vision of health. The magazine glorified a narrow ideal of beauty (typically white, lean, and muscular) as the epitome of human potential.

Ugliness Is A Sin

In Bernarr’s world, women were to be trained for motherhood as a form of patriotic labor, and children were treated as visual proof of inherited fitness. He personally promoted marriage contests to pair the physically perfect and urged laws to prevent the “feeble-minded” from breeding.

He saw immigrants (especially poor ones) as carriers of weakness. Disease. Moral decay. The slums of New York weren’t just dirty to Macfadden, they were degenerate. He believed the only way to save America was to make its bodies stronger, its borders firmer, and its bloodlines cleaner.

Macfadden never called himself a eugenicist, but his magazines regularly published eugenic content.

Over time, Macfadden’s movement embraced eugenics more directly, blending scientific authority with populist morality to construct a vision of bodily perfection as a cornerstone of American identity.

Weakness was a crime. In his world, the strong had a duty to dominate, not out of cruelty, but out of evolutionary necessity.

Copaganda

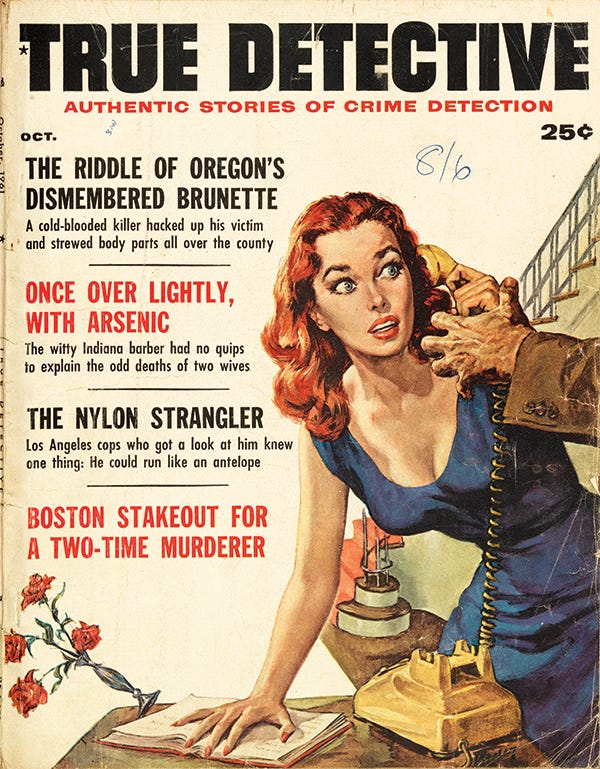

By the mid-1920s, Bernarr Macfadden had shifted from muscles to morality. With True Story already popular among women, he launched True Detective Mysteries in 1924, and it quickly became a cultural force.

What began as a pulp magazine filled with fictionalized crime stories eventually evolved into semi-journalistic tales of murder, perversion, and punishment.

Unlike the sensationalized, fictional stories in other pulps, True Detective presented itself as nonfiction. Gritty accounts of real murders, missing persons, and manhunts. It blended tabloid voyeurism with moral panic, often dramatizing the depravity of working-class criminals or femme fatales while reaffirming the heroism of police, detectives, and the state.

It cast criminals as the degenerate “other”—mentally weak, morally soft, often foreign. It framed law enforcement as strong, righteous, white men doing battle in a collapsing world.

Epic Side Quest: Masked Justice

Edgar Allan Poe is widely credited with inventing the detective story with The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841). His detective, C. Auguste Dupin, is analytical, detached, and almost entirely cerebral.

Before 1910, detective fiction was largely a British invention rooted in rationalism and aristocratic control.

Characters like Sherlock Holmes reflected a world where the threat was disorder, but the solution was intellect. Crime was a puzzle, not a condition.

“Sherlock is utterly inhuman, no heart, but with a beautifully logical intelligence.” - Arthur Conan Doyle

In the United States, the tone changed. As cities grew and inequality widened, detective stories shifted from drawing rooms to gritty streets.

Birth of a Notion

Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel The Clansman was also a vigilante origin story.

The Birth of a Nation (1915) did more than revive the Ku Klux Klan; it reframed the masked vigilante as a heroic American archetype.

In it, Black politicians run amok, white women are under threat, and the government is paralyzed.

Into this chaos rides the Ku Klux Klan, not as terrorists, but as saviors. Masked, moral, and outside the law, they deliver the justice the state supposedly can’t.

This narrative quickly escaped the screen and entered real life.

Across the 1910s, white mobs increasingly adopted the imagery of masked justice, launching extrajudicial attacks on Black communities, immigrants, and labor organizers.

Black Mask of Morality

The hard boiled pulp detective emerged in the 1920s and 30s, shaped by immigration, Prohibition, racial tension, and the obvious failures of both police and political elites.

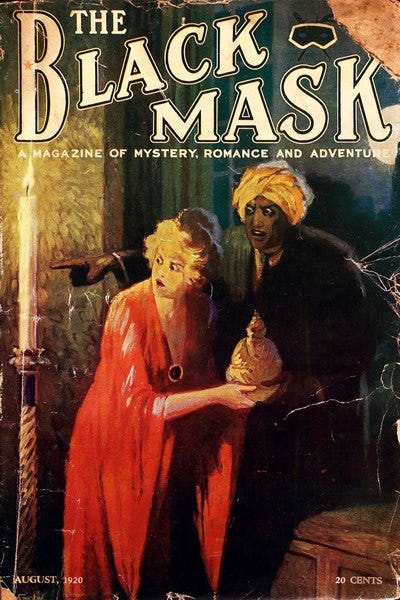

Magazines like Black Mask became arenas for characters who didn’t trust the system and solved problems with fists or firepower.

These detectives were not solving crimes to preserve order; they were enforcing personal codes in a broken world. Their enemies were corrupt businessmen, foreign gangsters, femme fatales, and bureaucrats with blood on their hands. This was not just noir; it was working-class justice wrapped in violence and moral ambiguity.

Hatecraft

Writers like H. P. Lovecraft publishing in overlapping pulp markets during the 1920s and 30s, carried that anxiety further.

Lovecraft imagined horror as racial and civilizational collapse, often driven by immigrant cults or racial hybrids contaminating “pure” bloodlines.

“The Negro is fundamentally the biological inferior of all white and even Mongolian races.” “The Jews are more dangerous than the Negroes because they are cleverer.” - HP Lovecraft (from his letters)

The Horror at Red Hook (1925), the threat is explicitly tied to immigrant communities in New York, a mix of “Syrians, East Indians, and Mongoloids,” which Lovecraft described in dehumanizing terms.

Dick Tracy, FBI

Dick Tracy had a direct and deliberate connection to state power, especially in his early years, serving as a kind of propaganda tool for law enforcement. Created in 1931 by Chester Gould, the strip emerged at the height of Prohibition, a time when public confidence in police and the justice system was deeply shaken by the rise of organized crime and corruption.

Gould, an ardent believer in law and order, crafted Tracy as the idealized face of modern policing; incorruptible, efficient, and equipped with cutting-edge technology.

The strip’s portrayal of crime-fighting closely aligned with the image J. Edgar Hoover was cultivating for the FBI at the same time.

Tracy was often seen using forensic science, radio communication, and surveillance tools in ways that echoed the Bureau’s self-mythologizing campaigns. Gould’s vision of justice wasn’t just moral; it was technocratic and punitive.

His grotesque villains (Flat Top, Pruneface, the Brow) were physically deformed, a visual shorthand for their moral depravity. These weren’t people gone wrong; they were monsters from birth, echoing early eugenic and ableist ideologies that conflated appearance with criminality.

By the 1940s, Dick Tracy had become a symbol of federal-style policing (even though he was nominally a local cop) and was used to legitimize emerging techniques like wiretapping and portable surveillance.

The strip helped normalize the idea that extraordinary crime required extraordinary force, a logic that would later echo in Cold War surveillance culture, anti-communist policing, and urban "tough on crime" rhetoric.

The Barbarian King

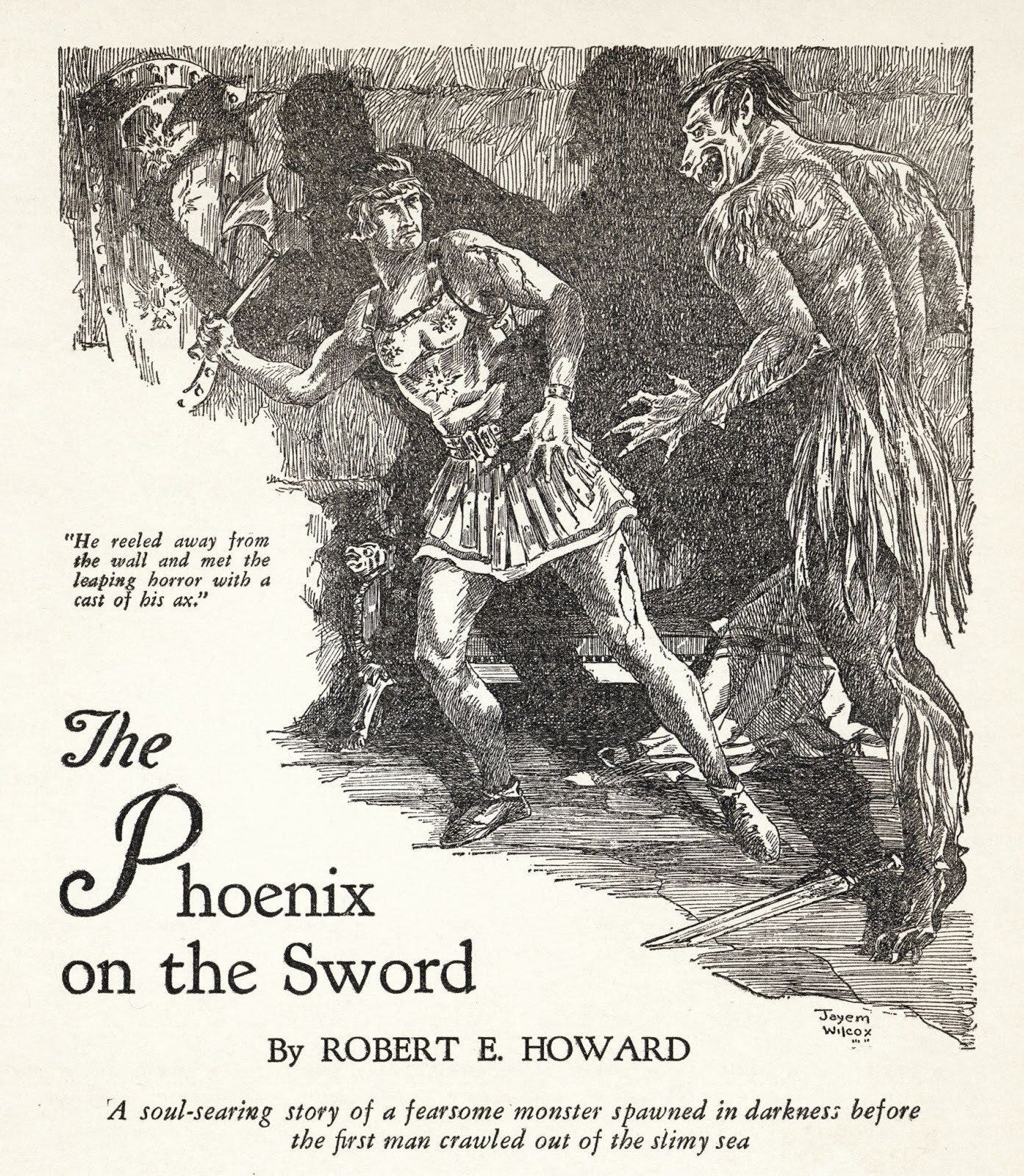

Lovecraft’s friend Robert E. Howard responded with barbarian heroes like Conan, who embodied white masculine restoration through violence, upholding order not with intellect, but with the sword.

Before Conan became a franchise (before the comics, Frazetta paintings, or Schwarzenegger) he was introduced as a grim, brutal character in a decaying civilization, drawn from Howard’s mythic vision of history.

In "The Phoenix on the Sword," published in Weird Tales magazine in December 1932, Conan has taken the throne of Aquilonia by force.

Conan is portrayed as a better ruler than the corrupt nobles, despite being a “barbarian.” In this framework, the sack of Rome (or any empire) is not just inevitable, it’s necessary. It clears away the rot.

But Conan was not aspirational in the modern superhero sense. He was reactionary, a fantasy of white masculine reassertion in a world falling apart.

The Reign of the Superman

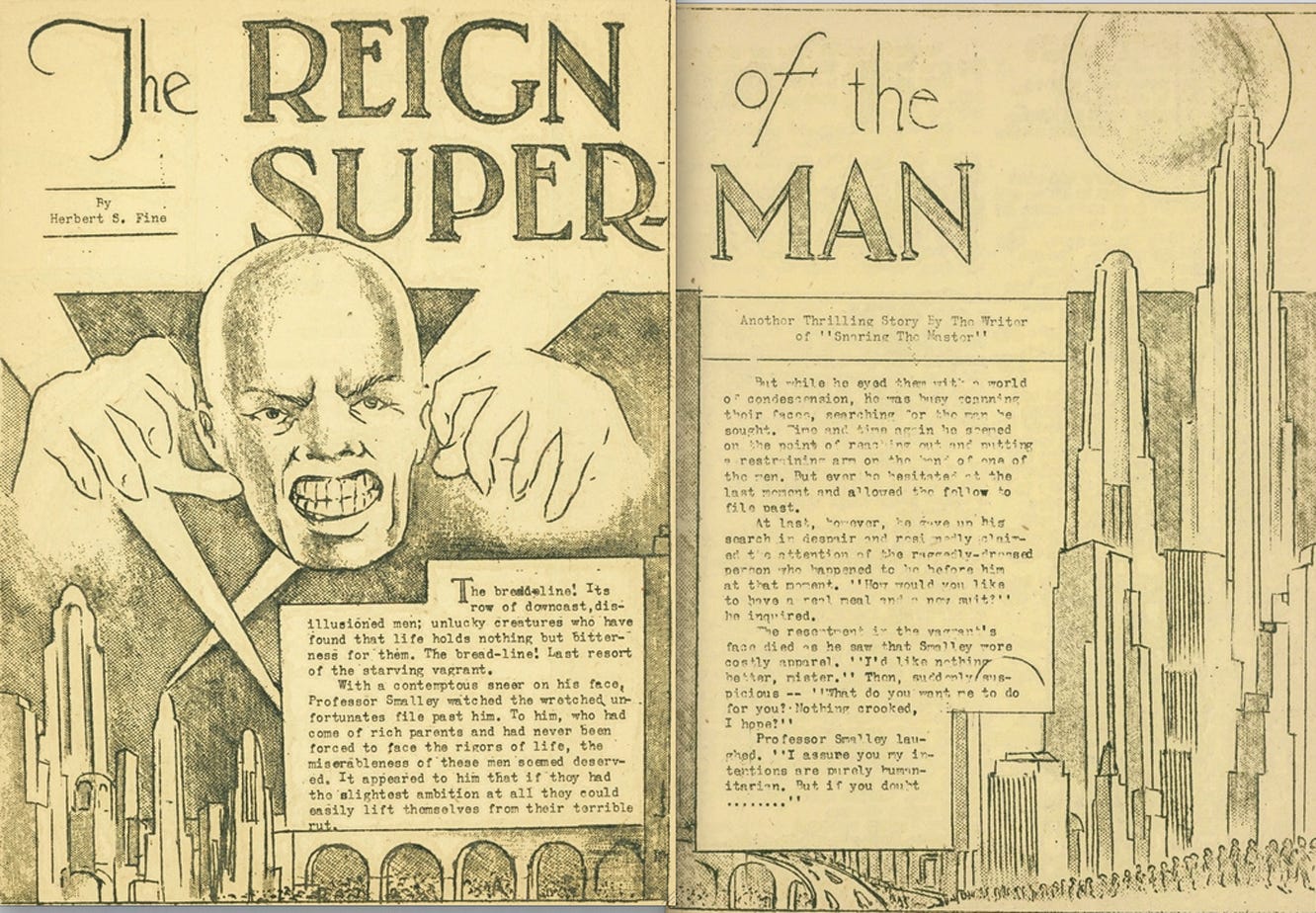

Before Superman was the red-caped hero we know today, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created a short story titled The Reign of the Superman in 1933. It was self-published in a mimeographed fanzine called Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization, one of the earliest American science fiction fan publications.

The story features a villain, not a hero. A down-and-out man named Bill Dunn is given telepathic powers by a mad scientist. With these abilities, Dunn becomes a megalomaniacal tyrant, seeking world domination. He is not physically strong, but mentally, a prototype for Lex Luthor.

In the years that followed (especially amid the growing threat of fascism and the hardships of the Depression), they reimagined Superman as a champion of the oppressed.

Superman’s revised role became that of a godlike figure who chooses humility and service. Luthor resents Superman precisely because he sees himself as the rightful apex of human potential, undermined by an alien god. Bill Dunn’s role (human power corrupted) became Lex Luthor’s.

By 1938 (when Action Comics #1 was published) Superman had been completely rewritten as a hero from another world, raised by humble farmers.

The Dark Knight

If Superman was the a benevolent strongman, then Batman was something else entirely. Created just a year later, in 1939, Batman emerged not as a symbol of collective hope but as a tool of controlled fear, a masked enforcer who worked in the shadows to uphold a fragile status quo.

While Superman pulled people from burning buildings and stood against war profiteers, Batman stalked alleyways, beat muggers, and protected banks. He didn’t fight inequality; he punished its symptoms. In the mythology of the era, Superman belonged to the people. Batman belonged to the property class.

"I would also remark that save for a smattering of non-white characters (and non-white creators) these books and these iconic characters are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race. In fact, I think that a good argument can be made for D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation as the first American superhero movie, and the point of origin for all those capes and masks." -Alan Moore

America’s Hero

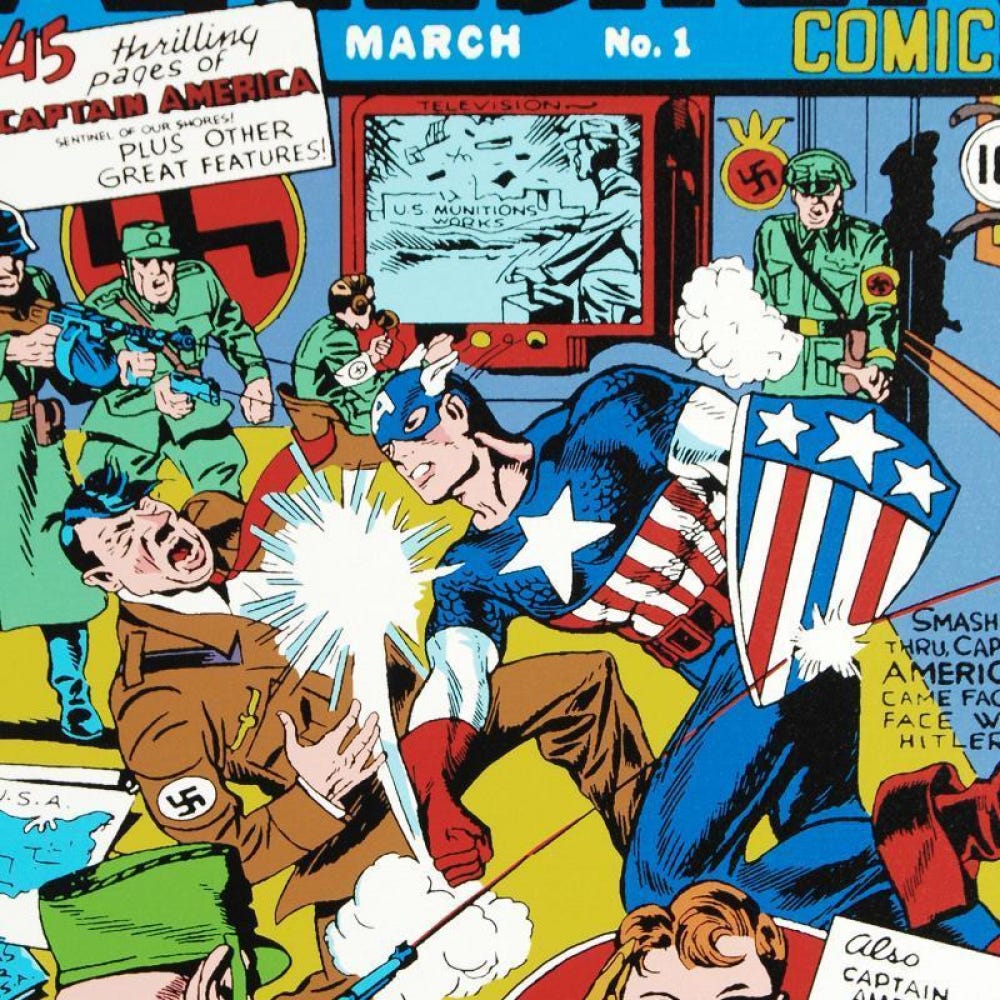

Timely Comics was founded in 1939 by Martin Goodman, a New York-based pulp magazine publisher who saw the early success of Superman and decided to enter the comic book market. Like Superman and many films and publications of the time, it was essentially wartime propaganda.

Introduced in 1941, just before the U.S. entered World War II, Captain America was not a vigilante but a state-sanctioned superman, created by science, wielding a shield instead of a weapon, and punching Hitler on the cover of his debut issue.

This was the updated American myth: that strength could be earned, that morality could guide might, and that the ideal man could represent the state without being absorbed by it.

Timely would eventually become know as Atlas Comics before being rebranded in the 60s as Marvel comics.

Get With the Program

By the 1920s, Macfadden had built recuperation centers offering kinesitherapy and hydrotherapy, and handed out degrees in “physcultopathy.” He mingled with Upton Sinclair, George Bernard Shaw, Rudolph Valentino, and Mussolini.

MacFadden admired Fascist Italy’s health programs, praised Mussolini’s vision of a strong and unified body politic, and at times advocated for an American dictatorship to restore national vigor.

In 1935, as the Great Depression ground on and Franklin D. Roosevelt expanded federal power, Macfadden announced his candidacy for president as a challenge to both the New Deal and what he saw as America’s moral and physical decay.

His platform included mandatory physical education and health reform as national policy. A crusade against “medical quackery”(ironically, as he was widely considered one himself by the AMA).

He positioned himself as a savior of the American body, warning that sloth and softness were destroying the country. His slogan might as well have been: Make America Fit Again.

In one startling 1940 proposal, he suggested that Americans who attained “physical perfection” should be rewarded with extra votes at the ballot box, since their superior discipline presumably made them better citizens

By the 1940s, his star was fading. Medicine professionalized. Eugenics fell out of fashion after the Holocaust. His empire crumbled.

But his gospel lived on, not just through bodybuilding and American gym culture, but also in Kennedy’s fitness campaign.

The Soft American

In her memoir, Times to Remember (1974), Rose Kennedy (matriarch of the Kennedy family) mentions that she was an avid reader of Bernarr Macfadden’s magazines, particularly Physical Culture. She admired his promotion of health, clean living, and self-discipline, and incorporated many of his ideas into the upbringing of her children.

Macfadden’s broader ideology (that physical strength was tied to moral strength and national greatness) resonated with Rose Kennedy’s Catholic values and vision of personal discipline, which she passed on to her sons, including John, Robert, and Ted.

Before JFK, fitness was considered fringe. But with Kennedy’s administration came the Presidential Council on Physical Fitness, a campaign to remake the American citizen as strong, clean, alert. Fit to fight communism.

Though John F. Kennedy publicly embraced modern medicine, especially after years of secret health struggles, the image crafted around him (young, tan, vigorous, playing football or sailing) mirrored Macfadden’s ideal of the muscular, photogenic American male as a symbol of moral and political vitality.

In 1960 he published an article called “The Soft American” in the new magazine Sports Illustrated.

In it, Kennedy grounds the case for fitness in Western civilization; from Ancient Greece and Roman stoicism to British imperialism (Eton fields as battle prep). He constructs physical fitness as a civilizational constant, linking bodily strength to intellectual excellence, moral clarity, and political vitality.

Sport’s Illustrated, found just a few years earlier, helped nationalize sports fandom, turning athletes into icons, merging journalism with hero-worship, and laying the groundwork for the modern sports-media-industrial complex. The introduction of the Swimsuit Issue in 1964 added another layer of cultural controversy and marketing genius, blending athleticism with objectified beauty.

Alongside Sandow and Charles Atlas, and in step with U.S. education, military, and health policy, Macfadden spent decades shaping both a physical mold and a national ideal. The strong, upright, disciplined man. The citizen whose body proved his virtue.

Macfadden died in 1955 after refusing medical treatment for a digestive disorder. His death marked the end of an era, but the mold he helped build was already in place.

The mold was just the physical body, a vessel for something else older far more sinister.