This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

For my new grandad, Kosher Kowboy, Neil Diamond was more than just a second cousin. Cousin Neil was a kindred spirit; a Jewish kid from nearby Sheepshead Bay, who was living the American Dream. He was achieving fame, earning respect, and building a fortune.

Though we rarely interacted with him, his presence loomed through his music, free concert tickets, and holiday gift baskets. When Neil Diamond sang America in 1980, he was offering a vision of the immigrant experience as pure hope, a final ascent into the promised land.

“Got a dream to take them there,

They're coming to America

Got a dream they've come to share,

They're coming to America…”

In the remake of The Jazz Singer, Diamond’s character leaves behind the synagogue and finds his true voice among Black musicians—crossing lines of race, culture, and sound.

The Kowboy carried that spirit of multiculturalism. He was a comedian so everyone was a potential audience for his latest set. Our neighborhood (Luna Park, Coney Island) was predominantly populated with Russian, Jewish, and Eastern European immigrants but my grandfather would speak to everyone and anyone.

I remember telling people my name was Michael because my real name seemed unpronounceable to many Americans. Or it got instantly demoted to “melon”.

I remember my first crush, a classmate named Bianca. I had a dream about her. We showed up in class wearing matching racing suits and drove motorcycles on the walls. That was probably informed by my trip to Ringling Bros circus.

The school was right across the street from my building. P.S. 90 The Edna Cohen School aka The Magnet School for Environmental Studies and Community Wellness.

Magnet schools were established in the United States as a voluntary means to desegregate schools by attracting a diverse student body.

Funded through the Magnet Schools Assistance Program (MSAP), they offered structured pathways into visual art, music, theater, dance, graphic design, film, and animation. For many Black, Latino, and immigrant students, these schools offered a way out, not just academically, but culturally and psychologically, by affirming creativity as a form of intelligence.

I remember my first teacher. She was a beacon in the blur of a new world—a calming, focused presence amidst my high energy existence. Her guidance was similar to other adults, but tempered, slower and more measured. Good teachers don’t just educate, they get through the noise.

I remember feeling shock and pride when I was presented with an “Art” award at my graduation. I may have been creative by then but I don’t know that it was something I did often. I mostly liked to play outside, which is what I did in Guyana.

After that “award” I began to identify as an artist. I remember my new grandfather, kosher Kowboy, introducing me to people in the neighborhood as “an artist.” It was a path, not just for me, but for my parents as well—something they could nurture.

God Bless the USA

P.S. 90 became the center of national attention in 2012 when Principal Greta Hawkins was accused of prohibiting kindergartners from singing Lee Greenwood’s God Bless the USA at their graduation ceremony.

The backlash was swift and intense, with critics accusing her of being unpatriotic. The drama continued when Republican Congressman Bob Turner turned the incident into political theater by inviting local children to stage a “protest recital” of the song in the school yard, the same yard I once played in. The event is hard to watch but the testimony from the locals at the end is extremely telling.

In truth, Greta’s tenure was cursed from the start.

In 2010, Hawkins was sent to sensitivity training after DOE investigators confirmed she made racially divisive remarks at a faculty meeting comparing herself (Black, Jehovah’s Witness) to her predecessor (white, Jewish).

An anonymous petition described a toxic work environment where staff felt bullied and feared retaliation for speaking out. They alleged Hawkins micromanaged lesson plans and retaliated against teachers who voiced concerns or filed complaints.

In the years following, Hawkins faced additional controversies, even a temporary reassignment amid an official investigation from the Department of Education. The press continued to lambast her, especially the NY Post.

From the start she had supporters who told another side of the story on this Facebook page, including the fact that the infamous patriotic song was difficult for children to remember and that there were other patriotic songs on the bill.

The page owners criticize the backlash as misinformation fueled by a small group of disgruntled teachers upset about being held accountable by a principled leader. They suggest these educators launched baseless personal attacks against Hawkins, possibly motivated by bias against her and/or her religion.

Despite these challenges, Hawkins was cleared of all charges and reinstated as principal where she remains to this day. But her haters have also not given up.

God Bless The USA was released in 1984, one year before I arrived in the US.

Country music singer Lee Greenwood performed the song at the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, where Reagan was formally nominated for a second term.

The song became an unofficial campaign anthem, playing at rallies and public appearances. I remember the song but I’m not sure if I ever had to learn it.

I do remember having to recite the Pledge of Allegiance every day, with a hand on my heart, leading to the common misconception that the heart is on the left side of your chest.

Greta Hawkins being A Jehovah’s Witness is noteworthy because they are one of the reasons The Pledge of Allegiance is not mandatory. Jehovah’s Witnesses’ faith prohibits saluting symbols or pledging allegiance to any government because it’s considered idolatry.

B-Side: The Pledge Of Allegiance

The Pledge of Allegiance was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy, a Christian socialist and former Baptist minister.

It was originally published in The Youth's Companion as part of a campaign to promote national unity and patriotism (especially among immigrant children) during the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas.

But it was first unveiled to the world at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago as part of a massive patriotic education campaign.

Yes. We are going to talk about The White City. Again.

The original wording of the pledge was:

“I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

It was accompanied by a salute and was intended for use in public schools.

Schools were given instructional kits to conduct pledge ceremonies. Students were to extend their right arm straight outward toward the flag during the recitation of the pledge.

Bellamy and others believed they were referencing a Roman tradition of saluting leaders or symbols.

19th-century art and sculpture, especially neoclassical paintings showing scenes from Roman history depict figures with arms extended in salute.

In The Oath of the Horatii by Jacques-Louis David (1784), three brothers (the Horatii) are swearing an oath to their father to fight to the death for Rome against the Curiatii brothers, their rivals from Alba Longa.

The women in the painting are crying because they are caught in the emotional and familial tragedy that lies beneath the public heroism of the scene. Rome wins the conflict but at a cost. The surviving Horatius kills his sister later for mourning a Curiatius to whom she was betrothed. The lesson: patriotism > family.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Italian fascists under Mussolini and later German Nazis under Hitler adopted a similar gesture: the straight-armed Roman salute, palm down. The Nazis claimed it was a revival of the Roman salute.

The “Bible Student” movement which began around the 1870s and became know as “Jehovah's Witnesses" made their opposition to the pledge public in 1935 when schoolchildren who were Jehovah’s Witnesses began refusing to salute the flag or recite the Pledge in public schools.

A year later, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the ideological collision between fascist spectacle and democratic myth played out in the most visceral ways. Black American athlete Jesse Owens won four medals that day, humiliating Hitler who had hoped the games would showcase Aryan superiority.

While many American athletes performed the salute, Owens pointedly stood at attention without raising his arm. His refusal was subtle but deeply symbolic, especially in a stadium filled with swastikas and Nazi salutes. It also exposed the contradiction of an American democracy that sent Black athletes to confront Nazi ideology abroad while upholding white supremacy at home.

During World War II, Congress officially recognized the Pledge in 1942 in the U.S. Flag Code, and many states and local authorities began requiring students to recite it. Congress also changed the official manner of delivery (to placing the right hand over the heart) to avoid the associations with the Nazi salute.

Just three years later, the Court reversed itself with West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, a landmark decision. The majority ruled that forcing students to recite the Pledge violated the First Amendment, protecting freedom of speech and religion.

America the Beautiful

I also distinctly remember learning the words to America the Beautiful and wondering what purple mountains were.

Not long after the incident with God Bless The USA , a super bowl commercial for Coca Cola featuring America the Beautiful also became a topic of controversy.

As the channel 11 news segment Brenda’s Last Word correctly notes, the poem was indeed written by Katharine Lee Bates, a closeted gay woman, in 1893.

The poem was inspired not only by the majestic view from Pikes Peak…

…but also by her visit to the (drumroll) 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

What is often overlooked is how the tone of America the Beautiful is actually critical.

The line “America, God shed his grace on thee.” is a prayer.

Bates was a dedicated social activist throughout her life. She was interested in the struggles of women, workers, people of color, tenement residents, immigrants, and the poor. Her young adult novel "Rose and Thorn" (1889) incorporated poor and working-class women as characters to teach about social reform.

America the Beautiful reflects her desire for an all-inclusive egalitarian American community.

In the original draft she asks God to shed grace on the nation until:

“…souls wax fair as earth and air /And music-hearted sea!”

The peaceful sky, earth, and air are presented as one harmonious sea, an example of a diverse world, in concert, not contest. She hopes the same for the American people.

In the second stanza she addresses the impact on Native Americans from “stern” pilgrims and “impassioned stress”.

This speaks to the settlers tamed the wild lands and the people.

She pleads with God to lend grace to future “pilgrims” as they stamp through “wild thoughts”. Meaning: frontiers aren’t just intellectual and external, they are also internal and spiritual. She hopes they also “bend a knee” (pray), practice self-control while they teach it.

The third stanza is most damning of all:

”O beautiful for glory-tale / Of liberating strife,

When once and twice, for man's avail, / Men lavished precious life!

America! America! / God shed his grace on thee

Till selfish gain no longer stain / The banner of the free!”

Here Bates is directly calling out the myth when she says “Glory-tale” noting how many men had given their lives in multiple wars in the name of freedom and that “selfish gain” sullies that honor.

In all drafts one haunting line in the closing stanza remained:

"Thine alabaster cities gleam,

Undimmed by human tears!"

A direct reference to the White City and the fact that in 1893, the U.S. was also deep in a depression. Cities like Chicago were full of unrest, child labor, poverty, and violent inequality. This is further echoed in the original ending:

“Till nobler men keep once again

Thy whiter jubilee!”

By calling for “nobler men” and a truer celebration, Bates is borrowing from the White City’s language and implying it was not pure enough.

Over time, Bates revised the poem, removing overtly moralizing language. Melinda M. Ponder, in her biography Katharine Lee Bates: From Sea to Shining Sea, suggests Bates was always walking a line between deep moral concern and public readability.

Eventually the poem was trimmed to the now-familiar first stanza. The result was a sanitized national hymn about geography, stripped of its moral anxieties and made suitable for classroom recitals, stadiums, and state ceremonies.

B-Side: 1492

Just like every American schoolkid of my generation, I was taught the rhyme:

In fourteen hundred and ninety two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

It’s from a poem called “A History of the U.S.”

What most were not taught is what else happened that year.

In 1492, the same year Columbus departed Spain, all Jews were officially expelled from the country under the Alhambra Decree, signed by Ferdinand and Isabella. Jews were forced to convert, flee, or die.

Over the last two decades, multiple genetic studies have added fuel to a long-held theory: that Columbus himself was a Sephardic Jew, a converso or “Crypto-Jew” navigating Catholic Spain’s purges.

There are many clues in his writings. Columbus often used Jewish dating systems, referenced Old Testament passages, and left cryptic Hebrew markings in the margins of his journals. Some scholars suggest he intentionally obscured his background, while hinting at it with pleasure—a kind of intellectual wink across the centuries.

Those who converted (Conversos or Crypto-Jews) often lived in constant fear, accused of secretly practicing Judaism, surveilled by the Inquisition.

For centuries, Jews in medieval Spain played a crucial role in society. They served as merchants, physicians, translators, tax collectors, and royal advisors.

These roles, though vital to the monarchy, were increasingly resented; Jews were visible in wealth management and court politics at a time when the crown was consolidating religious and national identity.

When the expulsion came, these practices were either seized, handed to conversos, or shut down entirely; property was liquidated, credit systems collapsed, and Spain lost a large portion of its financial infrastructure.

Many Jews ended up in Portugal and its Atlantic colonies, including Madeira—the sugar island referenced in Part 1: The Son, where the logic of plantation capitalism was first perfected:

Welcome to the Machine, Part 1

·Welcome to the Machine is a longform essay series tracing the fractured soul of the American man, through migration, masculinity, media, and myth. It’s part cultural retrospective, part personal excavation.

The Portuguese had just begun experimenting with sugar cultivation on Madeira, an Atlantic island colonized after 1419.

They cleared forests, built terraced plantations, and began importing enslaved Africans to labor in the fields. This is the template for plantation capitalism; a model of land seizure, monoculture, and forced labor.

Columbus’s wife was Portuguese; he lived on Madeira for a time and was already enmeshed in the logic of colonial extraction and trade networks before ever reaching the Caribbean. He was also funded in part by conversos. Luis de Santángel, a royal official of Jewish origin, helped finance the voyage after it was rejected by others.

1985

I arrived in 1985, when America seemed to be at a high point in its history. MTV, malls, CDs, and mass marketing made America look like a shining city on the hill.

Back to the Future (1985) wasn’t just a box office hit; it was a reflection of the kind of man America was trying to manufacture, and the new myth it wanted to tell about itself.

The contrast between 1955 and 1985 isn’t merely visual, it’s psychological.

Marty McFly inherits a landscape shaped by two archetypes: his meek, bookish father and the brutish bully who tormented him.

Biff represents a traditional, domineering masculinity: physically aggressive and sexually entitled. George McFly, by contrast, is passive, awkward, and paralyzed by fear.

Marty walks a narrow line between these poles. He doesn’t want to be the villain or the coward. He’s creative, emotionally open, and talented but also impulsive, insecure, and disorganized. He is, in effect, a prototype of the new American male—sensitive enough to be decent, tough enough to survive.

The film splits masculinity into two timelines: one where George accepts humiliation, and another where he throws a single punch and reverses his family’s fate. The reward isn’t justice; it’s material success, confidence, and a lifted social status. Biff is still present, just demoted. The system of dominance isn’t dismantled, it’s reversed.

Stranger still, is how Marty rewrites history; teaching his insecure father how to be bold, take risks, express himself (as Marty does with his guitar) using tactics established in the civil rights era.

In one of the film’s strangest turns, Marty becomes the secret progenitor of rock & roll. It’s not just a time-travel joke; it’s a metaphor for how American culture rewrites its own history.

What I didn’t understand then (but would come to see again and again) is that American masculinity doesn’t just live in men. It lives in systems. It’s in the schools, the media, the politics.

It’s in the way God is imagined and power is distributed. It’s the myth of the strong, rational, self-reliant man—descended from cowboys, soldiers, and factory dads. The Cold War didn’t just produce foreign policy. It produced The Father.

But it started way earlier than that. America was built upon a fundamental idea, one that has been buried or denied but not erased or forgotten. It’s a legacy whose reckoning has come.

Anthology: This Is America

1785: Oh, Freedom

Northwest Indian War (1785-1795):

One of the first conflicts involving the young US military and a confederation of Native American tribes (such as the Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, and Miami) in the Ohio Valley.

This war was a direct result of American westward expansion into lands recognized by the British as Indigenous territory before the Revolution. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne's victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 was a decisive moment in this conflict, leading further land grabs.

1808: Same Old Song

Because of domestic breeding and trade, southern slaveholders no longer needed to import slaves. The U.S. officially bans the transatlantic slave trade but slavery doesn’t end, it continues to expand within the United States.

1810: Money Trees

The cotton gin has changed everything. U.S. cotton production skyrockets. Cotton eventually exceeds 50% the value of American exports. The Deep South becomes the engine of American capitalism, Black bodies its fuel.

U.S. cotton exports reach ~53 million pounds, up from just 8 million in 1795

Enslaved population in the South increases by 70%

1813: Native Blood

Creek Wars (1813–1814)

General Andrew Jackson invades Creek territory beginning a campaign that will strip Native nations of 23 million acres of ancestral land.

Over 1,600 Creek warriors area. Another 20,000 Native people are displaced, with death tolls estimated in the thousands.

The war was framed as self-defense for the attack on Ft. Mimms but ends up being a land grab for southern planters and to assure safe passage of goods down the MIssissippi River and into the Gulf.

The Deep South’s plantation frontier begins. Andrew Jackson personally profited enormously from theses land grabs, acquiring thousands of acres in Alabama and Tennessee, prime cotton land.

For more about Andrew Jackson’s land grab:

The Paradox of Civilization

·Today, many descendants of European settlers express anxiety over immigration, fearing an erosion of the “civilized” culture they believe defines their national identity. Yet not long ago, their own ancestors arrived uninvited on shores already home to societies rooted in sustainability, kinship, and tradition.

1817: Seminole Wind

Seminole Wars (1817-1858)

A series of three brutal campaigns, the Seminole Wars represent a stark illustration of American expansionism and the violent dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

Despite the Seminoles' tenacious resistance it culminated in the forced removal of approximately 3,000 Seminoles to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) as part of the broader Indian Removal Act. Estimates suggest 4,000-7,000+ died from warfare, disease, and forced removal.

1819: The Fabric of Our Lives

America’s first major depression in the US hits, tied to land speculation, cotton prices, and credit bubbles. The economic collapse exposes how deeply slavery is embedded in the national economy. Cotton’s volatility becomes a national threat.

1820: Draw the Line

Missouri enters as a slave state, Maine as free. A line is drawn: no slavery north of 36°30'. The compromise is meant to keep peace but really, it formalizes the country’s split personality. Expansion will now always trigger crisis.

1821: Californio Dreaming

Mexico becomes a republic and inherits control of California, Texas, and the Southwest. American settlers (including slaveholders) begin entering Mexican Texas, laying the groundwork for future conflict.

1828: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

Jackson rides a populist wave to power. Indian killer, slaveholder, and man of the people. His rise signals the coming age of removal, white supremacy, and aggressive expansion. Jackson becomes the first Imperial president.

1829: Fight The Power

President Vicente Guerrero, a Black man of Afro-Indigenous descent, abolishes slavery throughout Mexico. But Anglo settlers in Texas (many of them from the American South) refuse to comply. They bring enslaved people into Mexican territory, defy the law, and demand exemptions. Mexico’s anti-slavery stance becomes a direct threat to the U.S. cotton frontier.

1830: The Long and Winding Road

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 sets the stage, displacing over 100,000 Indigenous people from the Southeast. The land they leave behind becomes cotton country. What looks like destiny is actually logistics. Ethnic cleansing in service of monoculture.

1833: A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall

President Andrew Jackson orders federal funds withdrawn from the Second Bank of the United States and redistributed to hand-picked state “pet banks.” Congress never approved it—but Jackson doesn’t care. He sees the Bank as a monument to elite control, and he’s determined to destroy it.

He made paying off the national debt a major priority of his administration and he achieved this through high tariffs and the sale of vast amounts of land in the west.

This is the only time in American history when there was zero debt.

But the move destabilizes the financial system and fuels a wave of land speculation and reckless lending. The people cheer. In less than 4 years the economy tanks.

1835: Remember the Alamo?

Texas Revolution (1835–1836)

Anglo settlers in Mexican Texas (many of them slaveholders who defied Mexican law) declare independence. The myth says it was about freedom. In reality, it was about protecting slavery and white land claims.

After the Battle of the Alamo and the victory at San Jacinto, Texas becomes a breakaway republic—a rogue state built on bondage, just waiting for annexation. The myth becomes national scripture: Remember the Alamo!

1837: Hard Times Come Again No More

Just four years after Jackson drained the national bank, the economy implodes. The Panic of 1837 hits: banks fail, credit dries up, businesses collapse.

Land speculators go bankrupt. Unemployment spikes. Food riots break out in major cities. The South clings to cotton profits propped up by slavery, but “free laborers” starve. The so-called “common man” Jackson claimed to defend now pays the price for his war on finance.

1838: Where the Streets Have No Name

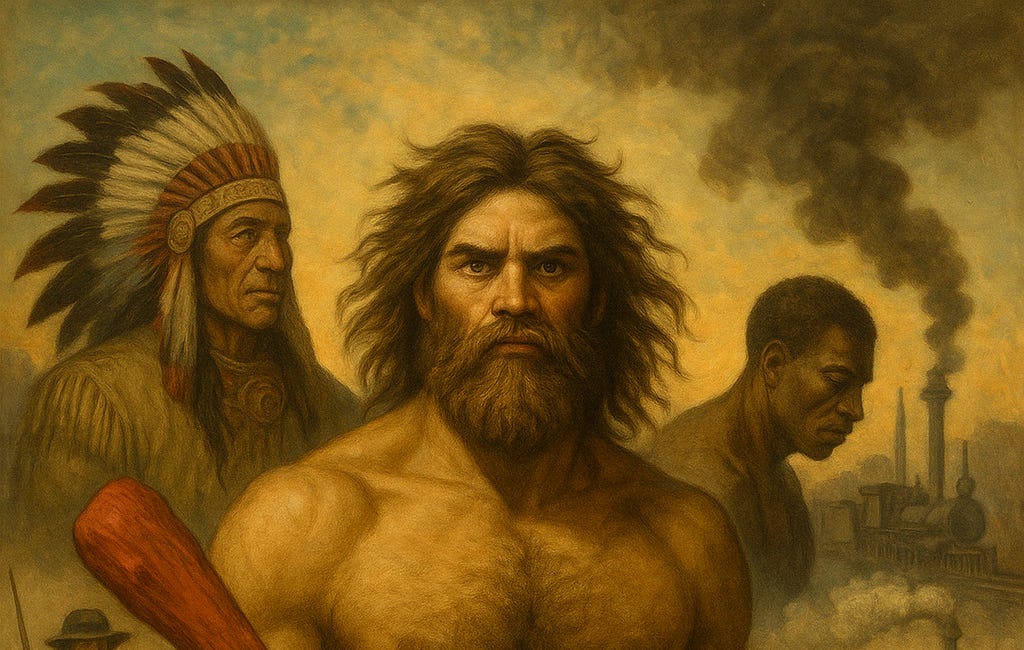

In the wreckage, the U.S. looks outward. Trade, science, and new resources become the answer. Within a year, the government funds a global voyage to chart new markets, assert power, and map the future.

The U.S. Exploring Expedition sets sail with scientists, guns, and survey maps. They don’t conquer. They name and chart.

Nearly every stop was chosen strategically with imperial, commercial, or scientific exploitation in mind, even when cloaked in the language of “discovery”, “exploration,” or “natural history”.

At least 8 locations on the Wilkes Expedition route became critical imperial nodes, especially as coaling stations, naval bases, or trade choke points.

Several became permanent military assets of the U.S. or other Western powers.

If Columbus was the mythic explorer, Wilkes was the modern operations planner, a man with empire on the mind and capitalism in his toolkit.

1842: The Dock of the Bay

Charles Wilkes calls San Francisco Bay “the most important harbor on the Pacific coast.” American merchants and military planners already see it as a gateway to China, a rival to British ports, and a staging ground for Western expansion.

The same year, as the legend goes, a Californio rancher Francisco López was napping beneath an oak tree in Placerita Canyon, dreaming of gold. It’s the first documented gold discovery, but it’s on Mexican soil.

1845: God’s Plan

America declares it has a divine right to conquer the continent. Expansion becomes sacred, and every piece of land becomes a battlefield over who will labor, who will rule, and who will vanish.

1846: No Church in the Wild

Mexican-American War (1846–1848)

The U.S. invades Mexico after provoking a skirmish near the Rio Grande. Under the banner of Manifest Destiny, American forces seize California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

The Mexican-American War ends with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, and half of Mexico’s land becomes U.S. territory. The new border is drawn but it poses a new question: which of these new lands will become slave states?

1848: John Horse

A U.S. Attorney General's ruling effectively stripped Black Seminoles of their freedom, making them vulnerable to slave raids despite earlier promises. Facing this betrayal, John Horse and the Black Seminoles made a radical choice: a planned exodus to Mexico in 1849, where slavery was abolished, securing their only true path to liberty.

1849: Gold Digger

Once seized, the West is repurposed. Gold is mined, railroads are laid, land is parceled and sold. White settlers flood in with deeds and guns.

Hundreds of thousands pour into California chasing fortune. Most find nothing. The gold discovery was largely embellished to encourage settlement and expansion. Countless indigenous people are displaced or slaughtered in the process. Mexican landholders are also pushed out. Water, minerals, and labor are claimed like prizes.

The gold rush is really a land rush and a story of who gets to own the future.

1850: Peacekeeper

California enters as a free state, but the South is compensated: a brutal new Fugitive Slave Act is passed, calling for special commissioners to determine whether slaves were fugitives.

1851: Gold Mountain

Thousands of Chinese immigrants begin arriving in California. Some are refugees escaping famine and economic instability exacerbated by the Opium Wars, others are drawn by rumors of wealth from the Gold Rush. To the latter, America is Gum Saan—“Gold Mountain.”

They work the mines, build railroads, open shops but face immediate hostility, racist taxes, and eventual exclusion. Their arrival marks the beginning of large-scale Asian immigration to the U.S., and the start of a long fight for belonging in a country that welcomed their labor but rejected their presence.

1852: What’s Going On

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin electrified abolitionist sentiment in the North but stoked defensive rage in the South. Abraham Lincoln reportedly greeted her as “the little lady who started this great war.”

Stage adaptations (some even before the book was finished) warped the story into melodrama and minstrel caricature. Uncle Tom, once a Christ-like martyr who protected Black women and children, became a cultural slur: docile, subservient, broken.

1854: There Will Be Blood

The Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively repeals the Missouri Compromise. New territories will vote on slavery themselves via “popular sovereignty”. Behind the entire debate of state-rights vs federal rights, was a railroad industrial complex seeking to connect and expand and the imbalances caused by slave labor vs free labor.

This triggered mass migration into Kansas, both from pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, hoping to influence the vote. But led to the fracturing of the Democratic party, the creation of the Republican Party, and the violent conflict known as “Bleeding Kansas”, a prelude to the Civil War.

1861: Battle Hymn of the Republic

American Civil War (1861–1865)

Confederate forces fire on Fort Sumter. The war is about slavery.

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea [of equality]; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery… is his natural and normal condition.”|

-Alexander H. Stephens, Confederate Vice President1865: Chain Gang

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, but with a loophole. Involuntary servitude remains legal "as punishment for a crime." Plantation owners pivot to convict leasing.

1866: Freedom Ain’t Free

With no land and no wages, newly freed Black families are forced into sharecropping agreements with their former enslavers. On paper, it’s a partnership. In practice, it’s a rigged debt cycle. Landowners provide tools and seed—but also cook the books. At harvest, the split always favors the master.

Landowners set the terms (sometimes up to 70% interest rates), the store sets the prices, and the debt sets in. It was by design a rigged system to keep bodies in servitude.

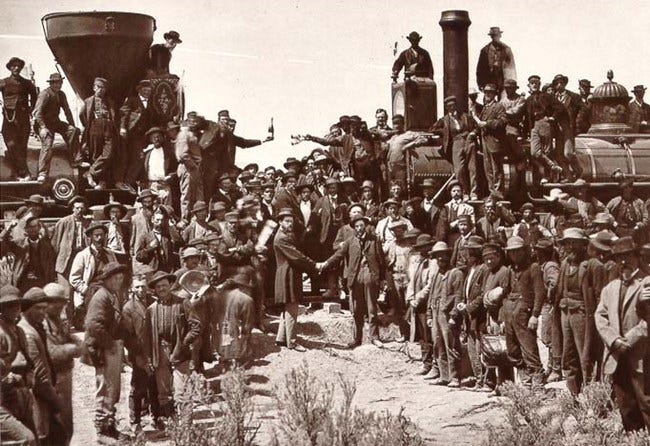

1869: This Train

The Transcontinental Railroad is completed, linking East to West, and opening vast new territories to commerce, industry, and speculation. It’s a signal to the world: America is hungry for labor. Railroads need workers. Cities need builders. Mines need diggers. The floodgates open, not just for goods—but for bodies. Though Chinese workers did much of the work, they were purposefully excluded from the iconic photo celebrating it’s completion.

1870: Immigrant Song

With Black labor locked in Southern sharecropping and prisons, Northern industrialists turn to Europe. Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Slavic immigrants flood into cities, fleeing famine and war. Over 50% of the immigrants came as indentured servants looking for work.

The Naturalization Act of 1870 expanded citizenship rights to formerly enslaved Black Americans but closed the door to almost everyone else. The law declares that only “white persons” and “persons of African descent” can become citizens, excluding Asians, Indigenous people, and most immigrants from the global South. Citizenship is no longer just about law, it’s about lineage.

1875: A Change Is Gonna Come

On paper, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 promised equal access to public spaces regardless of race—schools, transit, theaters. It was the last gasp of Reconstruction’s moral vision.

But that same year, the Page Act slammed the door on Chinese women, framing them as prostitutes and moral threats. The law is really about blocking family formation and population growth among Chinese migrants.

It follows decades of exploitation: Chinese laborers built railroads, drained swamps, worked mines—but as soon as the work was done, they became a threat. White politicians warned of the “Yellow Peril.” Labor unions blamed Chinese workers for wage suppression. Capital needed their bodies, not their presence.

1876: Now That the Buffalo's Gone

Great Sioux War of 1876

Despite the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie recognizing the Black Hills as sacred Lakota Sioux territory, the discovery of gold in 1874 by a U.S. Army expedition under George Armstrong Custer triggered a massive influx of illegal white prospectors.

This led to a series of bloody battles, most famously the Battle of Little Bighorn where Custer and his command were annihilated, a stunning, though ultimately temporary, victory for the Lakota and Cheyenne led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

Despite this Native American triumph, the war ultimately resulted in the U.S. forcing the tribes onto smaller reservations and seizing the Black Hills, marking a critical and devastating blow to Indigenous sovereignty in the American West.

1882: Get Back

The Chinese Exclusion Act bans Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. It’s the first law to prohibit immigration based on race and class. It comes after years of violence: lynching, burnings, forced removals from towns across the West.

Chinese workers had laid thousands of miles of railroad track, then were told they didn’t belong. The act freezes immigration, bars naturalization, and sets a precedent: that whiteness is a national boundary, and laborers of color are welcome only when silent, disposable, and temporary.

1883-1896:

1896: I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free

The Supreme Court's infamous Plessy v. Ferguson decision legally sanctioned "separate but equal" facilities for Black and white Americans, effectively codifying segregation and providing the legal framework for the Jim Crow system to flourish across the South and beyond.

This judicial betrayal coincided with (and emboldened) a brutal era of racial terror, as white mobs increasingly resorted to lynching (often public spectacles of violence) to enforce racial hierarchies, suppress Black political participation, and maintain economic subservience.

This period was about a pervasive culture of white supremacy that used both legal doctrine and ritualized violence to systematically dispossess Black Americans of their fundamental rights and humanity.

1898: Spanish Bombs

The Spanish-American War

While presented as a noble intervention for Cuban independence, the war resulted in the U.S. gaining significant control over the island.

The Teller Amendment initially disavowed any intention of exercising control over Cuba. However, the subsequent Platt Amendment (1901) forced Cuba to grant the U.S. the right to intervene in its affairs, effectively establishing Cuba as a U.S. protectorate. This set the stage for decades of U.S. dominance over Cuban affairs.

1899: The Imperial March

Philippine-American War (1899-1902)

The explosion of the USS Maine, though likely an internal accident, served as the pretext for a nation eager to assert itself on the world stage.

This brutal, prolonged conflict began when the United States, having acquired the Philippines from Spain, refused to recognize the independence declared by the Filipino revolutionaries. Instead, the U.S. sought to establish direct colonial rule.

Armed with brand new modern rifles and early machine guns like the Gatling gun, the filipino’s never stood a chance. They were wiped out almost effortlessly. Scholars estimate the death toll to be as high as one million.

1900: Not Like Us

The turn of the 20th century saw an unprecedented surge in immigration, with over 20 million newcomers entering the U.S. and often crowding into cities already bracing for collapse.

This demographic shift ignited a wave of nativism, as native-born elites increasingly viewed the issue not merely as one of overcrowding, but of "purity".

Fueled by Malthusian panic and the pseudo-science of eugenics, which advocated for sterilizing the "weak" and promoting the "fit," poverty was often pathologized and racialized.

In this climate, America's fear of difference began to solidify into legislation, setting the stage for decades of restrictive immigration policies designed to control not just labor, but the perceived racial composition of the nation.

Read more about this era and the early days of Coney Island in:

Welcome To The Machine 2: Jokers

·This essay continues my exploration of the contemporary American male’s relationship with masculinity and spirituality. It’s also my journey as an American male.

1910: Dubul' ibhunu

Britain unified its southern African colonies under white control, creating the Union of South Africa. It was a legal consolidation of racial power: white Boers and British settlers merged their rule, while Black South Africans were locked out of political life entirely.

1913: Beds Are Burning

The Native Land Act of 1913 was a foundational law in South Africa that legally restricted Black South Africans from owning or renting land outside designated "native reserves," which comprised only about 7% of the country’s land (despite Black people making up the majority of the population).

The Act effectively criminalized African land ownership, forced mass evictions, and locked Black South Africans into cycles of poverty and labor exploitation, particularly as migrant workers for white-owned farms and mines.

This marked the beginning of a white-run state built on racial exclusion, closely mirroring America’s Jim Crow system. The goal is clear: cheap labor, no ownership, no mobility. It’s apartheid in prototype

1914: Everybody Wants To Rule The World

World War I

Social Darwinists saw WW1 as a cleansing fire. Over 4 million non-white colonial troops fought and died for empires that denied them basic rights.

The postwar world rewarded conquest and redrew borders, but left racial hierarchies untouched.

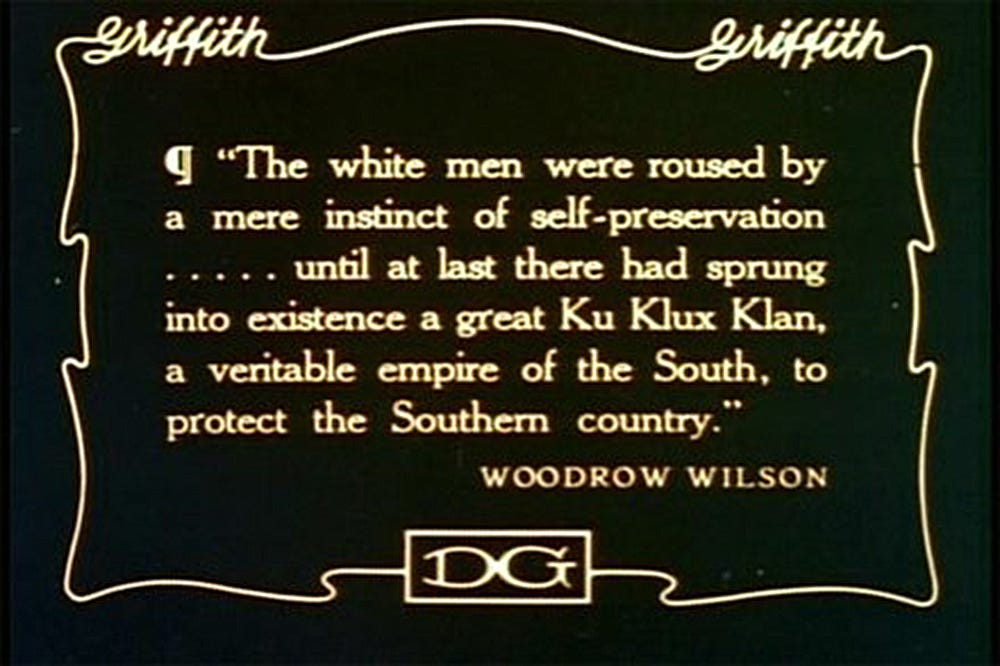

1915: The Ride of the Valkyries

Woodrow Wilson, a Southern Democrat, ushered in a stark reversal for racial equality at the federal level.

Upon taking office, Wilson's administration began to systematically re-segregate federal workplaces, including post offices, government departments, and agencies, many of which had been integrated since Reconstruction. He also hosted a screening at the White House of “The Birth of a Nation.”

Based on Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novel "The Clansman," it presented a deeply racist narrative wherein Black politicians were depicted as running amok, white women were under threat, and the government was paralyzed. Into this chaos, the Ku Klux Klan was portrayed not as terrorists, but as saviors.

1916: Born To Be Wild

Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916), warned that immigration and miscegenation (race-mixing) would doom Anglo-Saxon supremacy.

As chair of the New York Zoological Society, Grant had already supported the human display of Ota Benga, a Congolese man exhibited in a zoo cage.

He saw whiteness (specifically Nordic whiteness) as something endangered, to be protected like a species under threat. Benga eventually committed suicide.

1917: Strange Fruit

The East St. Louis Massacre is one of the most brutal and horrific acts of racial violence in American history.

Fueled by white resentment over the Great Migration of Black southerners seeking industrial jobs in wartime factories, and exacerbated by labor disputes.

After a false rumor of a white man's death at the hands of a Black resident, white mobs rampaged through Black neighborhoods, indiscriminately beating, shooting, and lynching Black men, women, and children, often burning entire blocks of homes and businesses and shooting residents as they fled the flames. Authorities, including police and the National Guard, were largely complicit or ineffective in quelling the violence.

1918: Crazy Blues

Spanish Flu pandemic hit Black and immigrant communities the hardest, exacerbated by overcrowded slums and medical neglect—many were simply denied service because of race. This was an outcome of systemic neglect, not nature. The total deaths from this pandemic were even greater than WW1.

It’s estimated ~55,000 black Americans were murdered or died from preventable causes during this 5-year period of the early 20th century.

1919: Homecoming

By 1919, Black veterans returned home from war in uniform. They were met with arson, lynching, and mobs. Over 25 cities exploded in what would be called the Red Summer—a coordinated attempt to reassert the racial order by force.

As the cities swelled, the response was not aid but containment. Prohibition (1920–1933), framed as moral reform, functioned as a pretext for surveillance and militarized policing, especially in Black and immigrant neighborhoods. The KKK provided security for the Anti Saloon League.

1920: Killing in the Name

Prohibition (1920-1933), often framed as a moral reform, served as a pretext for increased surveillance and militarized policing, particularly in Black and immigrant neighborhoods. The Anti-Saloon League teams up with the KKK.

While the wealthy could still access alcohol via doctors' prescriptions, the poor faced arrests and confinement. This era saw cities implementing "spotlights, towers, and checkpoints," effectively turning moralistic legislation into a tool for social control and further criminalizing marginalized communities.

1921: Black Wall Street

The Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the deadliest acts of racial violence in American history, erupted when a white mob, including deputized citizens, attacked the prosperous Black community of Greenwood.

Fueled by racial animosity and economic envy, the mob looted and burned over 35 blocks of "Black Wall Street," destroying hundreds of businesses and homes. Airplanes were used to drop incendiary devices, and estimates suggest hundreds of Black residents were killed, though official figures remain suppressed.

The event, largely erased from mainstream history for decades, epitomizes the violent lengths to which white supremacy would go to dismantle Black wealth and self-sufficiency.

1924: Club Can't Handle Me

The Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act) solidified the nation's nativist turn, severely restricting immigration based on national origin quotas and completely excluding immigrants from Asia.

Building on earlier discriminatory laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act, this legislation codified a racialized hierarchy, effectively determining who could enter the "melting pot" and who was deemed “undesirable”.

National Origins Act: would establish a quota system based on "national origins." It enshrined the idea that whiteness was a national boundary and that certain groups, particularly those from Southern and Eastern Europe, and especially Asia, were a threat to America's "racial purity."

1925: Bulls on Parade

On August 8, 1925, an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan, clad in their signature white robes and hoods, marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C. This massive demonstration was a chilling display of the Klan's formidable power and reach during its second, and most widespread, incarnation in the 1920s.

The purpose of the march was not subtle: it was a brazen assertion of white supremacy and "100% Americanism." The Klan, at this time, extended its virulent hatred beyond Black Americans to include Catholics, Jews, immigrants (particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe), organized labor, and those perceived as morally deviant.

The parade aimed to project an image of legitimacy and mainstream acceptance, showcasing the organization's millions of members and significant political influence, which, in some states, even extended to governors and state legislatures.

1927: The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fish peddler, were Italian immigrant anarchists arrested in 1920 and accused of a robbery and murder in Massachusetts. Their 1921 trial, presided over by a prejudiced judge in an era of intense anti-immigrant and anti-radical fervor, quickly became a global cause célèbre.

Despite questionable evidence and powerful public outcry, both were found guilty. After years of appeals and international protests, Sacco and Vanzetti were sent to the electric chair on August 23, 1927.

Their execution, widely seen as a miscarriage of justice fueled by political persecution, solidified their status as martyrs for social justice and eternal symbols of a system that prioritized fear over fairness.

1929: Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression exposed the brutal fragility of an economic system built on unchecked speculation and deeply embedded inequalities.

As financial markets collapsed, the working-class, multiracial underclass (already criminalized and confined by laws like Prohibition) was left to starve, surveilled but unsupported.

The crisis disproportionately impacted Black Americans, whose employment was often the "last hired, first fired," and immigrant communities already living in precarious conditions, revealing how systemic neglect, not just market forces, dictated survival.

1934: Dust In The Wind

The Dust Bowl, a series of devastating dust storms that swept across the American Great Plains in the 1930s, created an ecological and economic catastrophe. Exacerbated by decades of unsustainable agricultural practices like deep plowing and monocropping (driven by the very frontier expansion that dispossessed Indigenous peoples) the land literally turned to dust.

This environmental disaster forced hundreds of thousands of "Okies" and other displaced farmers to migrate westward, often into California, revealing the ecological consequences of unchecked capitalism and a short-sighted approach to land management, echoing the earlier land grabs that prioritized profit over environmental stewardship.

1942: Lost Freedom

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942, authorized the forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, from the West Coast into desolate inland internment camps.

This act of racial paranoia and wartime hysteria, justified by unsubstantiated fears of espionage and sabotage, stripped an entire community of their homes, businesses, and constitutional rights without due process.

It was a stark reminder that even citizenship offered little protection against the arbitrary exercise of state power when fueled by racial prejudice, revealing the fragile nature of liberty during times of national crisis.

1947: Ain't No Sunshine

Following World War II, the promise of the "American Dream" fueled a massive housing boom, but this dream was often deliberately denied to Black Americans through systemic racist practices.

"Redlining," a discriminatory practice by banks and real estate agents, systematically denied loans, insurance, and services to Black neighborhoods, deeming them "high risk." Simultaneously, restrictive covenants, legal agreements attached to property deeds, explicitly prohibited the sale of homes to non-whites.

This created racially segregated suburbs and urban ghettos, consolidating wealth in white communities and trapping Black families in under-resourced areas, actively shaping the economic and social landscape of postwar America.

1952: This Is My Country

The Immigration and Nationality Act, often known as the McCarran-Walter Act symbolically ended the outright ban on Asian immigration and removed racial and gender restrictions on naturalization but it largely preserved the discriminatory national origins quota system established in the 1920s, which heavily favored Northern and Western European immigrants.

This act also introduced stricter screening measures aimed at preventing the entry of perceived communist sympathizers, reflecting the heightened Cold War anxieties, and expanded the government's power to deport immigrants.

Despite a presidential veto, it passed, maintaining a system that continued to prioritize a specific racial makeup for the nation, even as it made minor concessions to global pressure for less overtly racist laws.

1954: Deportee

In 1954, the Eisenhower administration launched "Operation Wetback," a militaristic campaign to deport undocumented Mexican laborers. Despite the concurrent Bracero Program for legal workers, this operation, named with a racial slur, aggressively rounded up and expelled hundreds of thousands, often without due process, separating families and subjecting individuals to inhumane conditions. It underscored systemic exploitation and racism in U.S. immigration policy, leaving a deep historical scar.

1959: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

Fulgencio Batista's U.S.-backed dictatorship was overthrown by Fidel Castro's revolution. The revolution sought to end U.S. dominance and implement social and economic reforms.

The U.S. responded with a trade embargo in 1960, which continues to this day, and the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. These events dramatically reshaped Cuban-U.S. relations and had a profound impact on Cuban society.

1964: Mississippi Goddam

The Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, effectively dismantling Jim Crow laws.

This landmark legislation, a direct response to decades of systemic racial oppression and protest, prohibited segregation in public places, banned discrimination in employment, and mandated equal voting rights.

Its passage created a moral and legal climate that would eventually challenge the overtly racist foundations of existing immigration policies, paving the way for more equitable approaches to national belonging.

1965: People Get Ready

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) fundamentally transformed U.S. immigration policy by abolishing the discriminatory national origins quota system that had been in place since the 1920s.

Instead, it established a preference system based primarily on family reunification and skilled labor, significantly altering the demographic composition of new immigrants.

While President Lyndon B. Johnson downplayed its potential impact, claiming it "is not a revolutionary bill and does not affect the lives of millions," it inadvertently led to a dramatic increase in immigration from Asia and Latin America, sparking profound demographic shifts that continue to reshape American society.

1980: One Love

The Refugee Act of 1980 was a landmark piece of legislation that created the modern U.S. refugee and asylum system. It aligned the definition of "refugee" with United Nations standards, defining a refugee as someone with a "well-founded fear of persecution."

This act expanded the annual number of refugee admissions and established the Office of Refugee Resettlement, providing a more consistent and humanitarian framework for those fleeing persecution.

Born from bipartisan efforts, it solidified the U.S. commitment to providing a safe haven and opportunity for those displaced by conflict and human rights violations, although the program has faced challenges and reductions in subsequent decades.

Born in the USA

The Civil Rights era undeniably marked a significant (albeit incomplete) shift in the American status quo. These laws directly challenged legally codified discrimination based on race and national origin, theoretically opening doors that had been shut for centuries.

However, the political response to these seismic shifts, particularly in the subsequent decades, saw a backlash against the perceived overreach of government and a reassertion of conservative principles.

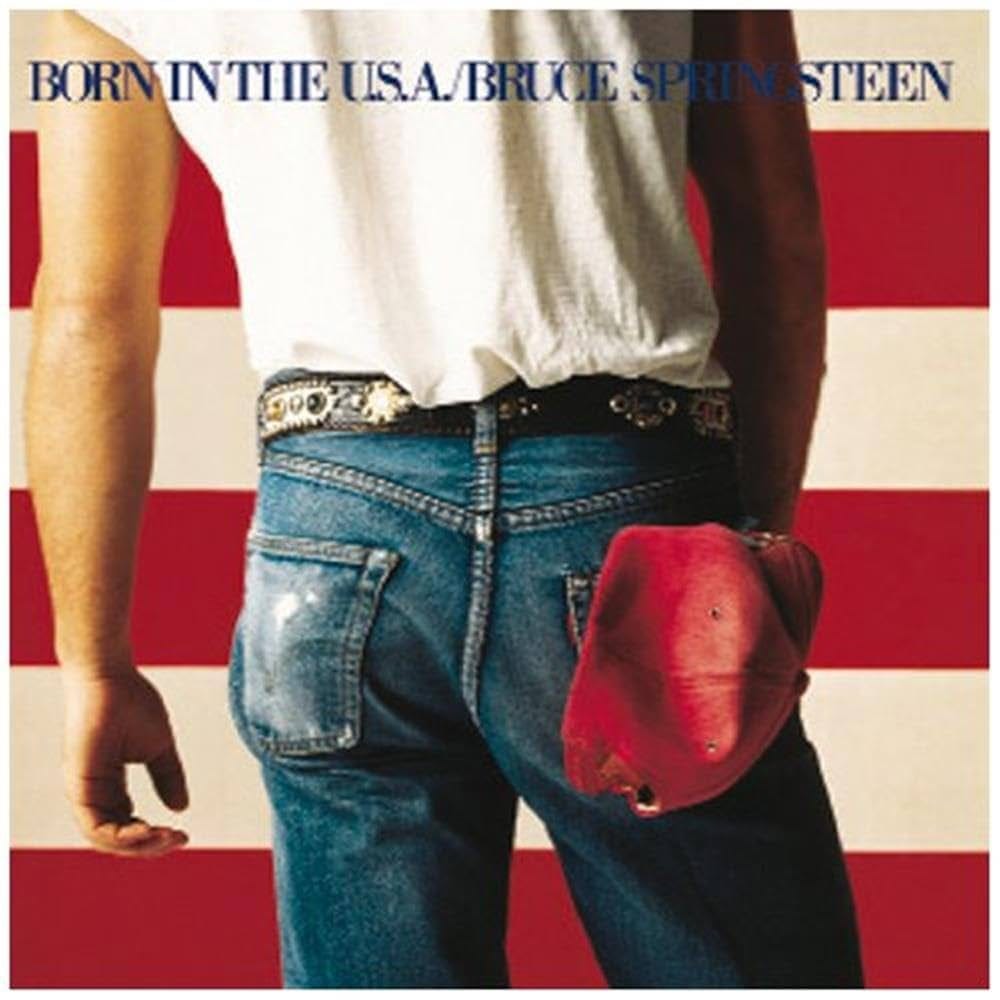

Four years after Neil Diamond’s America was a radio hit, Bruce Springsteen would record Born in the USA. Another American anthem, but this time, the sound was angrier.

Down in the shadow of the penitentiary

Out by the gas fires of the refinery

I'm ten years burning down the road

Nowhere to run, ain't got nowhere to go

The lyrics spoke not of arrival but of betrayal. Veterans abandoned. Workers discarded. Cities gutted.

It would become Ronald Reagan’s campaign song—even though Springsteen had written it as a cry of rage, not celebration.

Springsteen's chorus echoed like a man shouting into a canyon, trying to believe in a country that had already abandoned him. What sounded like pride was really grief.

Reagan’s reelection paved the way for the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986: an uneasy blend of amnesty and restriction, welcoming those already here while hardening the border against those still trying to come.

IRCA didn’t fix the real problem. It granted amnesty with one hand while tightening the borders with the other, trying to convince a wounded working class that the problem wasn’t the system that betrayed them. It was the stranger at the gate.

By 1988, even Eddie Murphy’s Coming to America was flipping the script—suggesting that sometimes, it might be better to return home.

The dream was still alive. But it was getting harder to find the front door.