Welcome to the Machine is a longform essay series tracing the fractured soul of the American man, through migration, masculinity, media, and myth. It’s part cultural retrospective, part personal excavation.

This series isn’t just about me, it’s about the systems that made me. The stories we were told, the ones we inherited, and the ones we swallowed without knowing. From the Cold War to cable TV, from John Wayne to Joe Rogan, I’m charting how history, economy, and image have shaped generations of men, especially those caught between cultures, between fathers, between worlds. This is also a story about true love and spirituality.

This is not a memoir. It’s a bridge. A path toward understanding, healing, and wholeness, for men, for memory, for a nation still trying to know itself.

This is for the boys.

Part 1: The Son

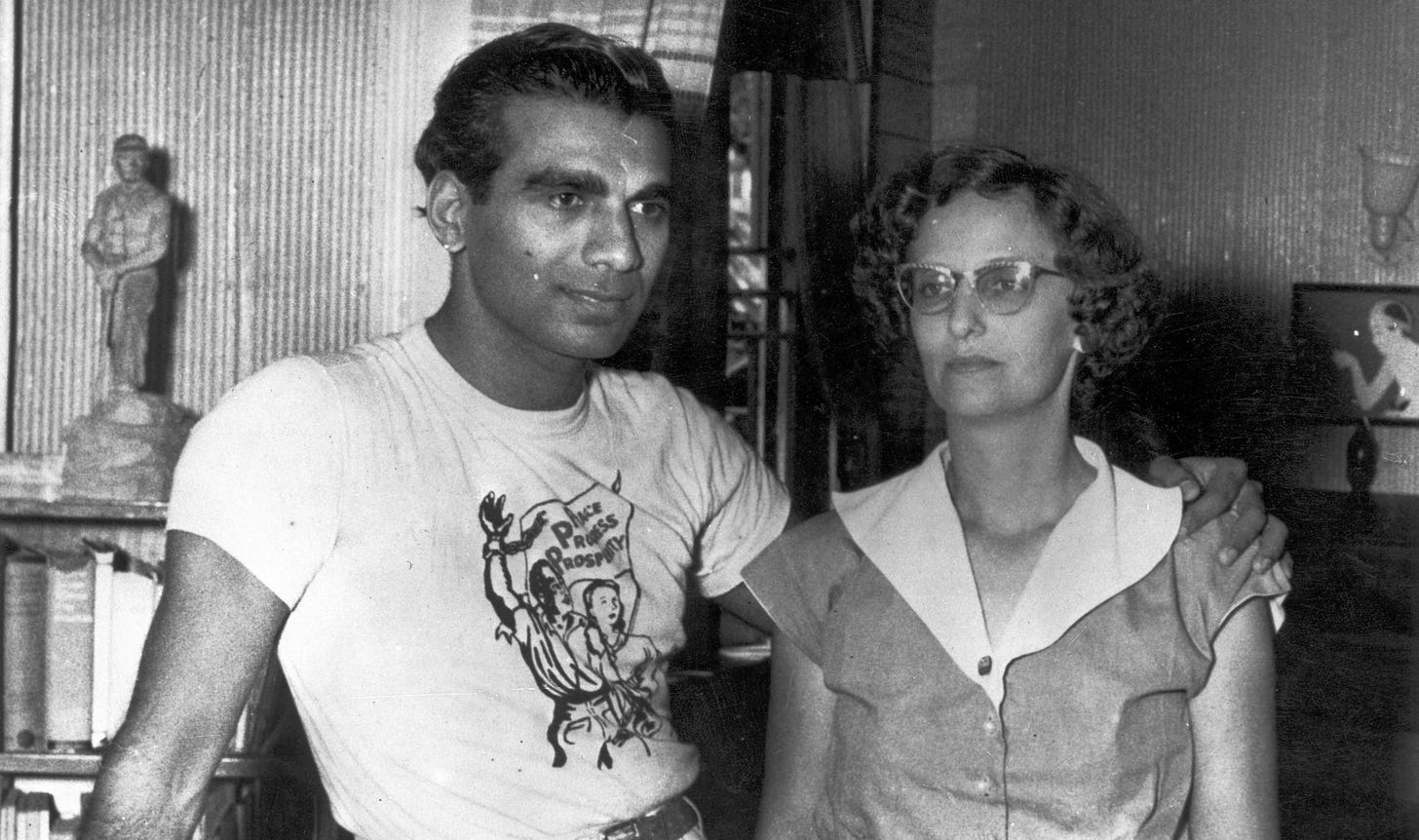

In 1985, I immigrated to the United States from Georgetown, Guyana. I was 4 years old. I landed in a two-bedroom apartment in the Bronx with my entire extended family; grandparents, cousins, aunts, uncles. I shared a bed with my single mother.

I don’t remember my real father. He stayed back in Guyana.

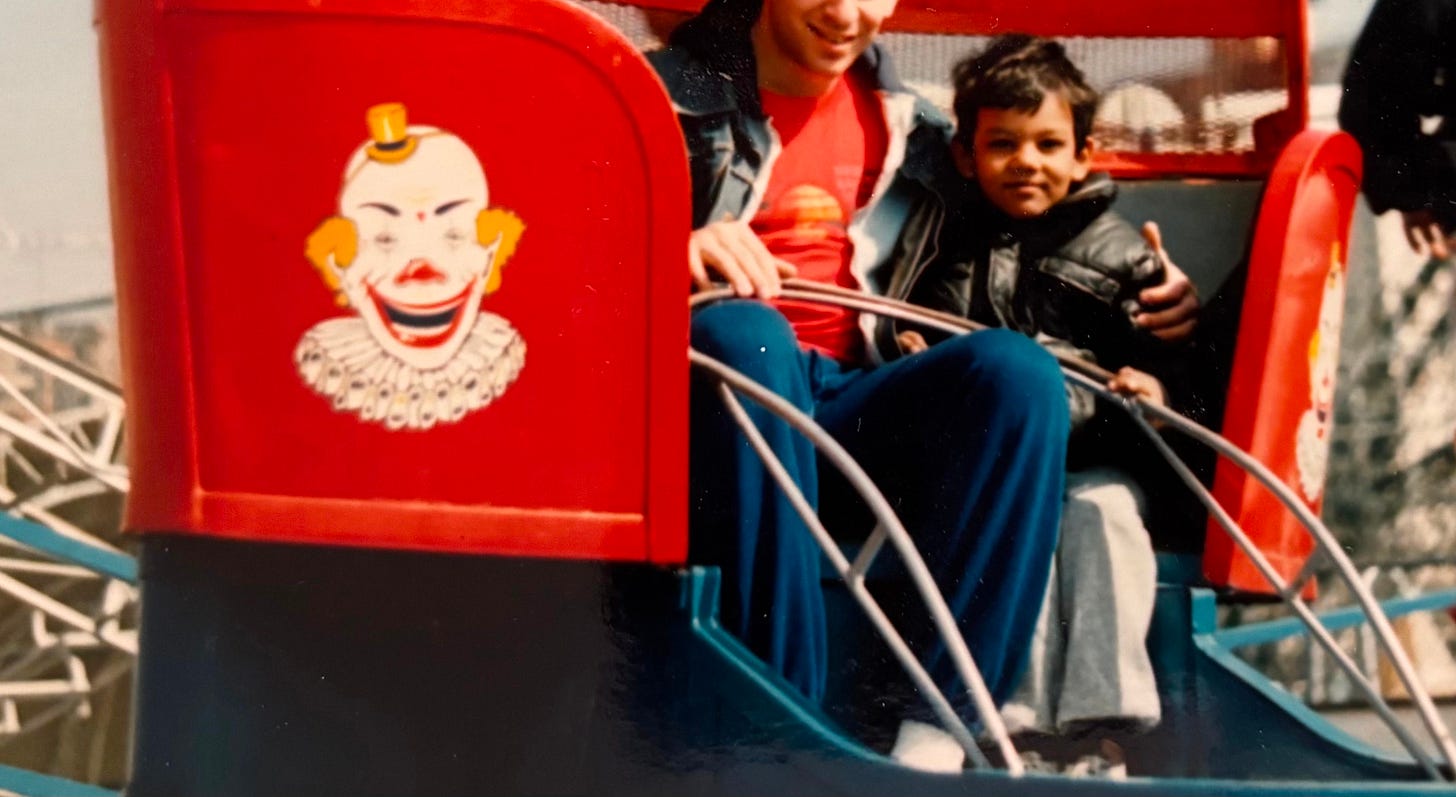

A few years later, my mother would marry a Jewish man from Coney Island. I would soon be adopted and eventually become a naturalized citizen. I’d also inherit a new family, a new last name, and a new trajectory.

yeah darlin' go make it happen

take the world in a love embrace

fire all of your guns at once

and explode into space

Like a true nature's child

we were born, born to be wild

we can climb so high

i never wanna die

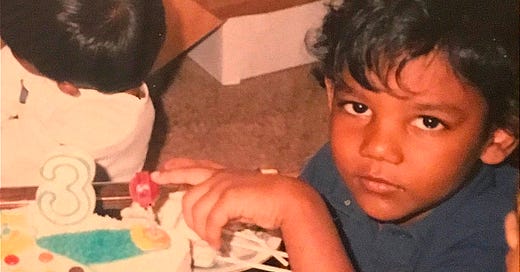

Here I am, about seven years old, cast into the American road fantasy, riding a toy motorcycle in front of a Brooklyn mall green screen while Born to Be Wild blasted behind me. A song about rebellion, made famous by the film Easy Rider (1969), about two men chasing freedom who are murdered, not because they break the rules, but because they don’t belong.

I was being drafted, slowly and invisibly, into the strange, contradictory brotherhood of the American male. Comics, action figures, music, movies, comedy, body image, rage. Discipline and shame. Status anxiety and ambition. Anti-authoritative and totalitarian. God and drugs. Globalism and Joe Rogan. It would all come…

But my story with America doesn’t begin in New York City. It doesn’t even begin with me. It begins with power and empire.

Because before I ever boarded that plane, the United States had already begun shaping the man I would be.

Guyana, Land of White Gold

Guyana was always caught between empire and illusion. In 1595, Sir Walter Raleigh sailed up the Orinoco chasing El Dorado and returned with a bestselling lie. The Discovery of the Large, Rich and Beautiful Empire of Guiana, captivated Europe and kicked off centuries of extraction. El Dorado was a lie, but the hunger it stoked was real.

When gold proved elusive, the empire turned its gaze downward, toward the rich, humid soil of the coastlands, perfect for growing sugar cane.

For centuries, sugar was luxury made edible. In Europe, it sweetened tea and defined class. Plantations weren’t just farms, they were factories of extraction, converting land, labor, and lives into profit.

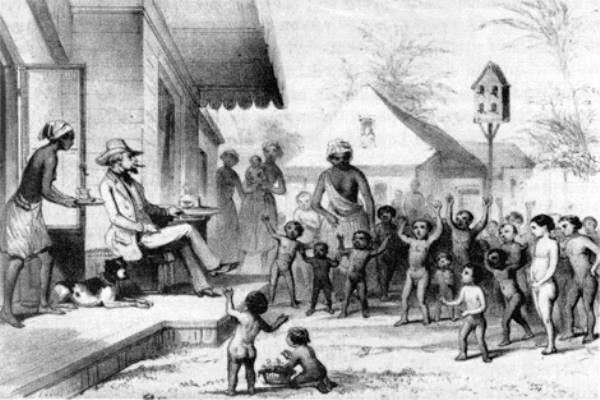

The Dutch arrived first, cutting dikes into wetlands and turning jungle into sugar. They brought with them shackled West African bodies from the Gold Coast, Congo, Senegal. They cut cane in Demerara, drained the swamps, laid the roads. The colony grew on their backs, and when they died, others were shipped in to replace them.

In 1823, nearly 13,000 enslaved Africans in Demerara rose up in one of the largest slave rebellions in the British Caribbean. Colonial forces executed hundreds.

The rebellion was reported in graphic detail by abolitionists.

A decade later, slavery was abolished across the British Empire.

After the abolition of slavery, plantation owners like John Gladstone (father of the future British prime minister) were desperate to keep the profits flowing. He was one of the first to import indentured laborers from India to British Guiana, replacing one caste of exploited bodies with another.

My closest ancestors were part of that exchange.

Guyana’s Son

My DNA tells a story shaped by empire and migration, but also by absence.

Indenture, slavery, and exile ripple through my lineage, but the deeper loss was spiritual: a severing from ritual, from rooted identity from a parent culture.

Long before empire drew its borders, before gold fever and flags, the land was already spoken for.

The Lokono and Kalina walked its rivers and coasts, mapped it in memory and sound. They farmed cassava, shaped canoes, traded stories, and believed the land could not be owned, only tended. They are the oldest inhabitants of the land and I carry a trace of their DNA. My grandfather still makes one of their traditional meals, Pepperpot, very Christmas.

The African side of my DNA came from those slaves in Demerara who built fortunes for plantation owners and never returned home. After abolition, they created free villages and led uprisings. They were the first builders of Guyana, though history rarely names them.

Nearly of third of my DNA came from Bengal. Indian Muslims pressed into indenture by promises of work, or simply survival. British recruiters (known as arkatis) scoured rural areas looking for laborers to sign contracts: five years of work on plantations in far-off colonies, in exchange for wages, housing, and the promise of return passage, which was often not honored.

Another large part of my DNA came from an island off the coast of Portugal; Madeiran Catholics who arrived in the Caribbean not as slaves, but as their replacements, contracts in hand and rosaries in pocket.

They were not called slaves, but they lived under the same sun, in the same fields, answering to the same empire. My ancestors on that side became craftsmen, masons, small-time merchants. They learned how to survive between power and poverty.

Origin Story: Birth of Capitalism

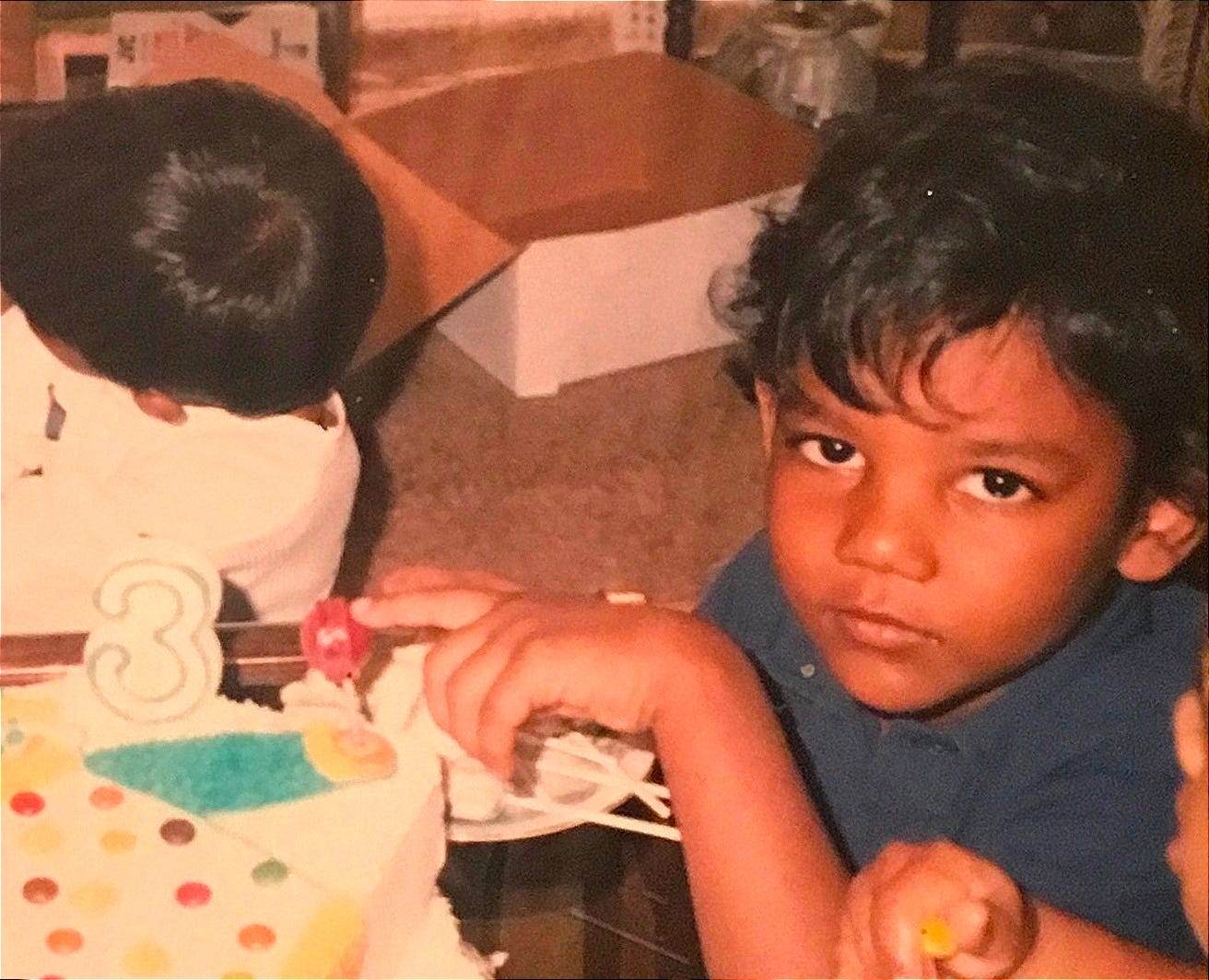

But as George Monbiot explains, capitalism did not begin in the markets of London or with the mythic barter system. It began in Madeira.

In the 15th century, Portuguese settlers:

Cleared the island’s forests

Planted sugarcane

Imported enslaved labor

Exported to distant markets

Exhausted all resources

This was the first place where land, labor, and life were stripped down to commodities. When the soil was exhausted, the system moved on, searching for new ground to consume.

The pattern was established: extraction, exhaustion, abandonment. Madeira was the beginning.

And everything that followed (the plantations, the colonies, the industrial empires) grew from that first wound.

Bauxite, The Element of World War

Sugar was the reason so many of my ancestors came, stayed, or were trapped. It built the colony’s economy and haunted its politics long after the cane fields went quiet.

But in the 20th century, another material made Guyana the center of attention for the world. Without this material, there would be no World War 2, no Cold War. It’s strategic importance made it more valuable than gold and made Guyana a target for the world superpowers.

It’s a reddish ore, dusty and raw, but inside it hides aluminum, lightweight, durable, and essential. Aluminum made the modern airplane possible. It built the wings of bombers, the skin of fighter jets, the frames of tanks, ships, even ration tins.

In the 20th century, aluminum became as critical to warfare as oil or steel.

And bauxite was the only way to get it.

During World War II, the Allied demand for aluminum exploded. The U.S. alone needed tens of thousands of aircraft. The race wasn’t just in the skies, it was underground. Whoever had bauxite had leverage.

Guyana had it.

And not just any bauxite, some of the highest-grade deposits in the world, dense and rich, buried in the tropical interior near the Demerara River.

First came the Canadians with ALCAN. Then the Americans with Reynolds. They laid down roads, built rail lines, carved out ports, not for the country, but for the ore. It was shipped out. The profits stayed abroad. Guyanese laborers did the digging, but never got a seat at the table.

Buy the 1950s, British Guiana stood at a political crossroads. The winds of decolonization were blowing strong. British Guiana was already politically awakened and uniquely volatile.

Origin Story: Socialists of Guyana

Guyana’s population was split, Indians vs Blacks. The British had used racial division to maintain control for over a century. By the 1950s, these divisions were deeply entrenched in neighborhoods, workplaces, unions, and party lines.

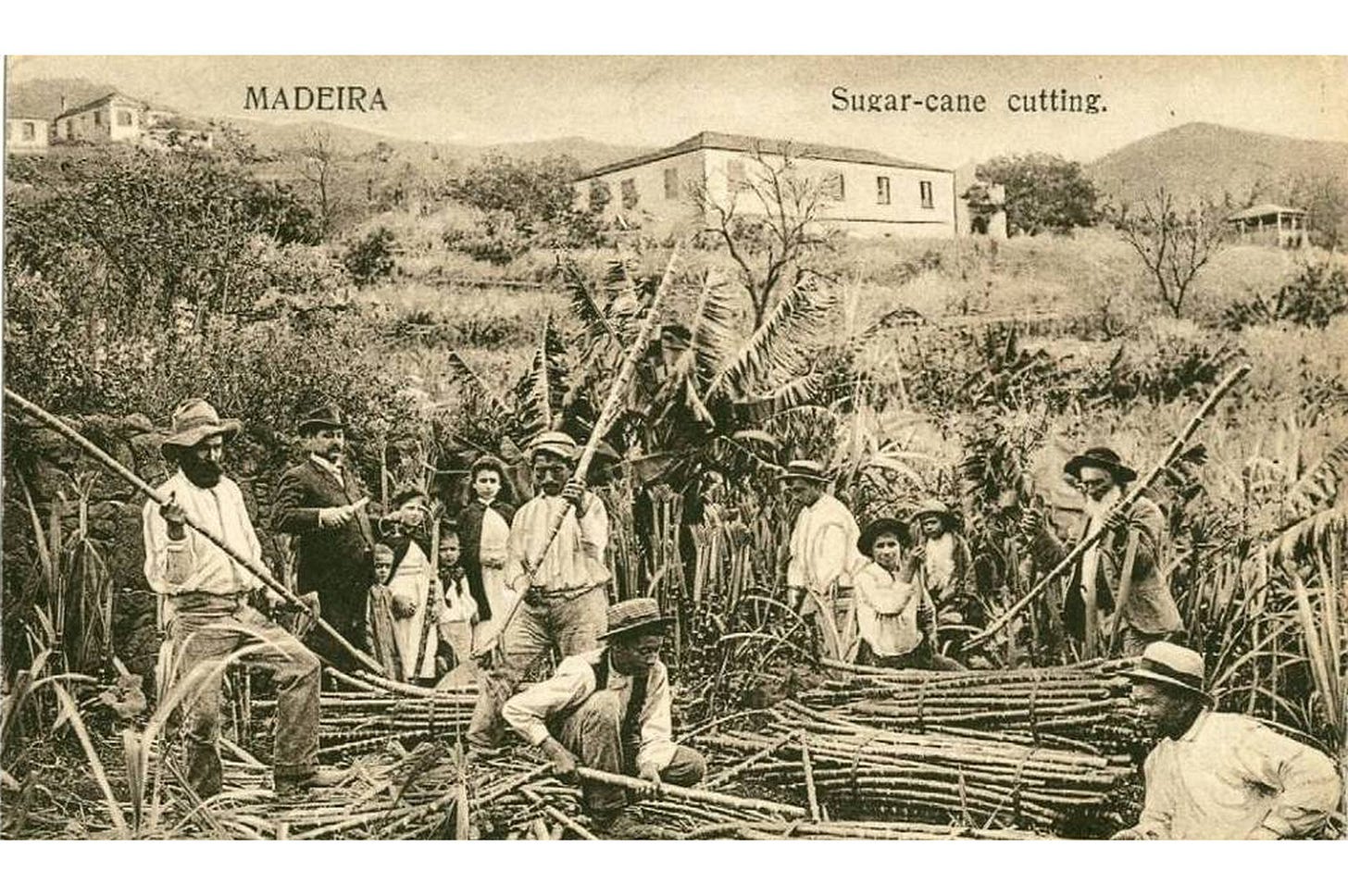

In 1950, Cheddi Jagan, a U.S.-educated dentist of Indian descent, co-founded the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) with his wife Janet Jagan, a white, Jewish-American socialist, and Forbes Burnham, a charismatic Afro-Guyanese lawyer. It was a rare multi-ethnic, leftist coalition pushing for workers' rights, land reform, and independence from Britain.

Jagan’s progressive reforms (especially his socialist leanings and interest in union empowerment) alarmed the British and Americans, who feared he was opening the door to communist influence.

While The US was using the Gulf of Tonkin incident as a pretext for war, the CIA was covertly funding riots, changing voting laws, and handing power to Forbes Burnham, a man they could control. He nationalized industry, then starved it. He called it “cooperative socialism”, but it was dependency in disguise. Jagan was exiled to the political wilderness.

This strategy (undermine, destabilize, then economically entangle) is precisely what John Perkins describes in Confessions of an Economic Hitman.

In this light, British Guiana was a textbook case. When military force failed to fully neutralize Jagan, economic tools took over. Loans were dangled, reforms demanded, and by the 1980s, Guyana was no longer a Cold War threat. It was a structurally dependent state, its sovereignty mortgaged in exchange for basic survival.

By the 1980s, Guyana’s local economy was in shambles. There was no currency. No fuel. No milk or flour. The lights went out. Bribes replaced wages. Bread lines around the block.

The U.S. didn’t need to send troops. It just let the system do what it was built to do.

This wouldn’t be the end of Guyana’s story. It would be the beginning of mine. For my grandfather and his family, it was the end of something.

Yes We Khan

By the 1980s, the country my maternal grandfather had grown up in was falling apart.

My grandfather was a jeweler. He learned to craft beauty from pressure, value from raw material. He had lived through empire, through coups, through flags changing hands. But this was different. The country wasn’t just poor, it was stuck.

It wasn’t an easy decision. Leaving meant replanting roots in someone else’s soil. But my grandfather saw what was coming. He didn’t leave out of defeat. He left because there was nothing left to build on.

So the family prepared. But not everyone was going.

My father worked in construction and as a mechanic. He ran his own garage. But he was also a huge pothead. My mother describes him having “piles of cannabis” on his work table, like Scarface had cocaine. When he fumbled a few big contracts there were fights about money. She packed our bags and went back to her father.

I never saw or spoke to my father again. I have no memories of him.

I don’t even know if he is still alive.

My mother didn’t just leave because of my father’s failures. Deeper than that was her longing for something else entirely. She was already American before she ever set foot there.

Raised on Western movies, pop music, and radio soap operas, she had been absorbing the fantasy for years. In her mind, America meant freedom; shopping malls, clean streets, happy endings. She wanted out of the noise, the struggle, the old tribal resentments. She wanted a future with fluorescent lighting and top 40 hits.

Although we were technically Muslim, religion wasn’t something

we practiced, it was something we inherited, like old furniture.

My mother never wore a hijab. She didn’t fast. She didn’t pray five times a day. She believed in God, I think, but not in rules. Not in guilt. Not in obedience. That was part of her Americanism. She wanted jeans, not jilbabs. Elvis, not Eid. She left religion where she left Guyana, in the past.

For her, America meant the right to choose your identity, not inherit it.

Faith was optional. Freedom was sacred.

For my mother, God was paternal, mysterious, and distant. But religion was a cage, not a practice. I was baptized but never handed a bible. Though my family had Muslim ceremonies, no one ever explained what that those prayers really meant. The ancient Hindu religion of my ancestors was merely a Bollywood aesthetic. Religion either wasn’t important or it was someone else’s responsibility.

I don’t know if my father was a devout Catholic or had any spiritual beliefs. He may have been careless, even cruel. He may not have cared whether I stayed or left. And yet, my mother has admitted she still loves him. I never got to find out if I did.

I wonder if the little boy missed his father before he forgot about him.

I didn’t just lose a father; I lost a mirror, a thread, a channel to something deeper. It was like being severed from a root system I never even got to feel. My mother gave me freedom, but at the cost of something ancient. Her rejection of faith, of lineage, of the man who made me, left me drifting. American, yes, but spiritually untethered. But maybe that helped me fit in.

Out of the Frying Pan

I don’t remember much of the Bronx, bits and pieces. I recall playing with toys in the house of my first friend Sammy, a black boy who lived next door. I don’t recall him at all but I named my first pets after him.

I remember my first snow. I remember exiting school to find the street dim during the day and a soft shower of white flakes falling. It was surreal. I remember the teacher telling everyone to catch snowflakes on their tongues. I found this quite challenging so I grabbed a handful from the hood of a car and ate it. Much more effective. I didn’t quite get the point.

When we arrived in the South Bronx in 1985, it had a bit of a reputation.

Fort Apache, The Bronx (1981), the South Bronx is depicted as a stage for criminals and junkies. A fortress under siege.

The film borrowed its name from an earlier myth: the John Wayne western Fort Apache (1948), where heroic cavalry soldiers battled "savage" Native Americans.

Throughout the 70s, TV news and newspapers were portraying the South Bronx as a warzone with both Police and Fire Fighters struggling to keep peace.

The South Bronx was portrayed by U.S. media as chaotic, dangerous,

and self-destructive. But the truth looked more like managed decay.

In the 1970s, basic services in the Bronx and other poor neighborhoods had collapsed: trash collection stopped, hospitals closed, and fire departments were systematically cut back.

Origin Story: The Inferno

From 1970-1980, there was on average 30-40 fires per day in the Bronx.

80% of housing was lost and nearly 250,000 people were displaced.In contrast, state pool insurance payouts were the equivalent of $50 million dollars today. It’s well understood now that insurance fraud was a major factor.

In Decade of Fire, filmmaker Vivian Vázquez Irizarry reclaims the story of the South Bronx fires from sensational media myths, showing how policy decisions, redlining, and insurance fraud (not the residents) set the borough ablaze.

The public story told about the South Bronx was that white families left (white flight) and the neighborhood fell apart because of savage brown and black residents.

In reality, landlords bought coverage worth more than their crumbling properties, then torched them for profit, leaving Black and Latino tenants homeless or dead.

In The Fires, journalist Joe Flood traces the true causes of the South Bronx infernos; not random chaos, but the cold calculations of bureaucrats. RAND Corporation computer models, commissioned by the city, added another layer: algorithms decided which firehouses and hospitals to shut down, almost always targeting poor, nonwhite neighborhoods for "efficiency."

It wasn't until 1980 (after a decade of devastation) that new reforms finally closed the loopholes. Insurers were forced to cap payouts and conduct real inspections. The fires slowed down almost overnight. NYC Firefighters still refer to this era as The War Years.

By then, entire neighborhoods had already been erased from the map. The South Bronx became a kind of domestic Gaza; abandoned, isolated, then blamed for its own wreckage.

Stayin’ Alive

The Bronx entered the 80s as a hollowed-out shell, with thousands

of abandoned lots, burned buildings, and vacant tenements.

Ronald Reagan made a brief campaign stop in the South Bronx in 1980, a move widely seen as symbolic rather than sincere. He spoke about law and order in a neighborhood already gutted by fires and disinvestment, promised "renewal" through free markets.

The city offered small programs to sell abandoned properties to tenant groups, but most rebuilding came from the ground up, block by block, with little help from outside. Media attention faded just as the residents began the slow work of survival.

Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, a grassroots tenant coalition, rebuilt abandoned buildings themselves.

And local activists like Hetty Fox helped youth learn to work the system in their favor, encouraging entrepreneurism. The community was healing, growing, and trying to work with the system.

And that’s when my family and I came in. We moved to the South Bronx because no one else would. I don’t have many memories of that neighborhood but I don’t remember a wasteland.

I didn’t have memories of Guyana. I didn’t miss it. My life began here. But I was already carrying its consequences, like how our thick accents thinned in public spaces. We had made it to America. But America hadn’t made us yet. We had to learn the language and customs, fit in.

Our home was still Guyanese. Curry on the stove. SOCA music on the stereo. The tribe was intact just in a new place. I didn’t know yet that this closeness (this density of love and noise) would fracture. That we’d scatter across states and cities. That we’d become nuclear, then remote.

My three cousins were my brothers and then slowly, I became an only child.

What I remember about the Bronx in the 1980s was more like Style Wars (1983); teeming with multicultural life, and color. The colorful subway murals instantly captivated me.

In the wreckage, kids were painting their names across subway cars. Dancers were turning concrete into stages. MCs were building new languages over stolen beats. The decay was more terrifying to white folks in the suburbs seeing it on the TV news. For the residents, it was just staying alive.

And you may look the other way

But we can try to understand

The New York Times' effect on man

Whether you're a brother or whether you're a mother

You're stayin' alive, stayin' alive

Feel the city breakin' and everybody shakin'

And we're stayin' alive, stayin' alive

In the Stayin’ Alive lyrics, The New York Times represents the elite, who are disconnected from street-level reality, maybe even manipulating it.

Saturday Night Fever (1977) showed Brooklyn’s working-class youth trapped between old-world traditions and a future shrinking around them.

For Tony Manero, the dance floor was a brief escape from dead-end jobs, family pressure, and a city in decay. Beneath the glitter of disco, the story was pure desperation: boys fighting to become men in a world offering fewer and fewer ways out.

Poor working-class whites, like their Black and Hispanic neighbors, were fighting to survive the collapse. But they were often pitted against each other by the true architects of the collapse: bankers, landlords, and city officials.

Where the Bronx was abandoned by fire, Brooklyn was abandoned by time.

It was there, at the end of the world, that I meet the man who I would call Dad.

No, I Am Your Father

I landed in the US just as The Empire Strikes Back was becoming scripture for a new American mythos. I didn’t know it yet, but I was stepping into the second act of someone else’s story, the part where the mask comes off and the truth hits like a blade. “No, I am your father,” Darth Vader tells Luke, not as comfort but as destiny.

That was the shape of the world I was walking into:

a machine that didn’t ask who you were, only who you belonged to.

I had arrived in America with no father, but I would soon inherit one. My mother got a job at a bank, working in what was then called "data entry", an early clerical cog in the machine. She met the man who would become my adoptive father in an elevator. The man who would become my father legally, but never quite spiritually.

Not just a man, but a model. A blueprint. A myth. And like all myths, he came with a shadow.

In the next essay, I will meet my new dad. He would teach me how to laugh and how to survive. He would introduce me to his American culture: rock music, comic books, action movies, wrestling…

But he would also teach me how anger can be passed down like a family heirloom, tucked beneath muscle, loud music, and addiction.

And I, already hungry for love and guidance, would take it all in.