Off To See The Wizard

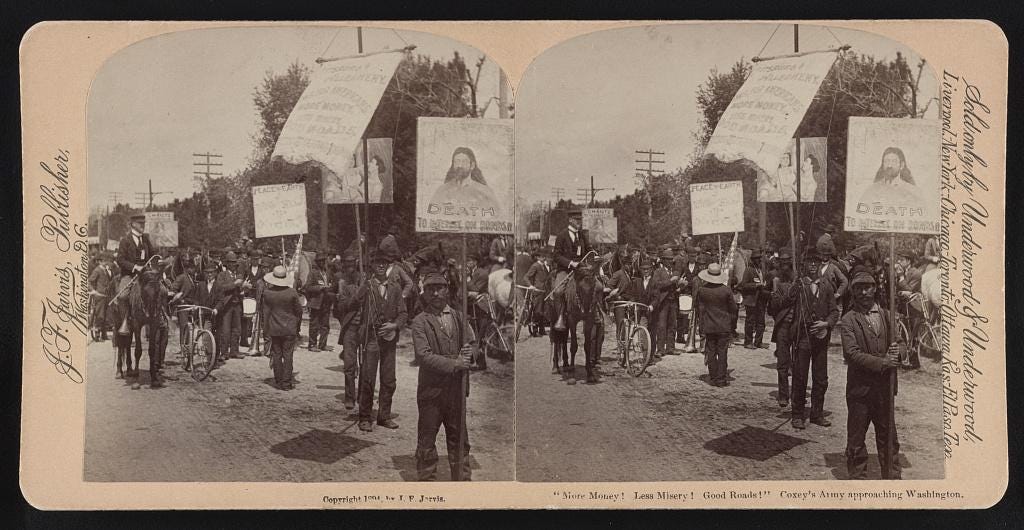

In the spring of 1894, a ragged procession referred to in the press as Coxey’s Army set out on foot from Massillon, Ohio, bound for Washington, D.C. They called themselves the Commonweal Army.

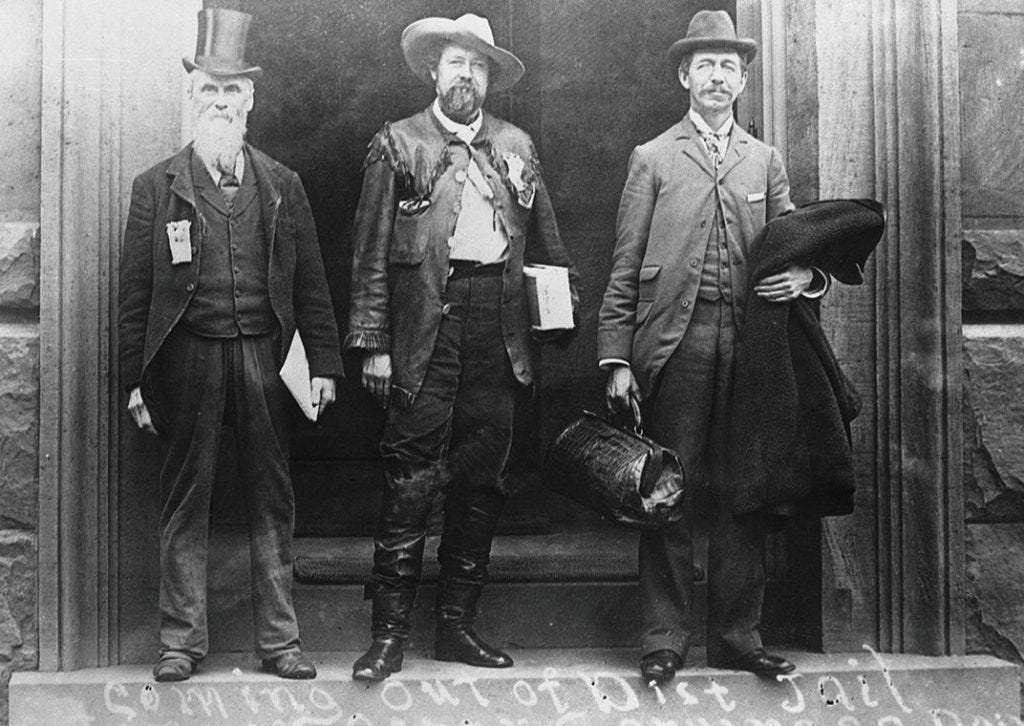

Led by Jacob Coxey, a mild-mannered businessman and Carl Browne, a long-haired mystic and artist in buckskins who claimed to channel the spirit of Christ. They were joined by labor organizer Christopher Columbus Jones and a small army of starving, unemployed men.

Notably, an African American man, carried the American flag at the front, a move that was praised by the African American newspaper The Washington Bee.

The march was a spectacle designed to make a political argument, emphasizing a unified nation and a multi-racial message of democratic peace. Despite contingents coming from other states, the Ohio group largely represented the broader movement.

The movement, also known as "The Industrial Army Movement," caused significant concern among the politically powerful, including President Grover Cleveland's administration, which dispatched Secret Service agents to monitor the marchers.

Upon reaching Washington D.C., the marchers were met with hostile reporting from many newspapers, which compared them to dangerous insurgents and claimed they were lazy or uneducated.

Coxey tried to give a speech about The Good Roads Bill (government-funded public works projects—a national road-building program and other public improvements to create jobs for the millions of unemployed workers suffering from the Panic of 1893.

They believed the government should take responsibility for providing employment during economic crises.

To finance these public works, Coxey advocated for the government to issue $500 million in non-interest-bearing Treasury notes.

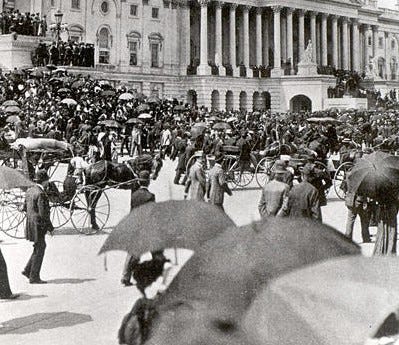

The peaceful marchers were met not with compassion but cavalry. Coxey was arrested for the crime of “walking on the grass.”

The Army dispersed, its demands unheard. But the ritual had been performed.

This was the first political pilgrimage to Washington D.C., a march to a hollow capital in search of justice. And it ended, like all American fairy tales, behind a curtain.

A Wonder Tale

You may have heard the theory (put forth by high school teacher Henry M. Littlefield in 1964 ) that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) is an allegory for the economic turmoil of the 1890s, especially the Panic of 1893 and the debate over the gold vs silver standard.

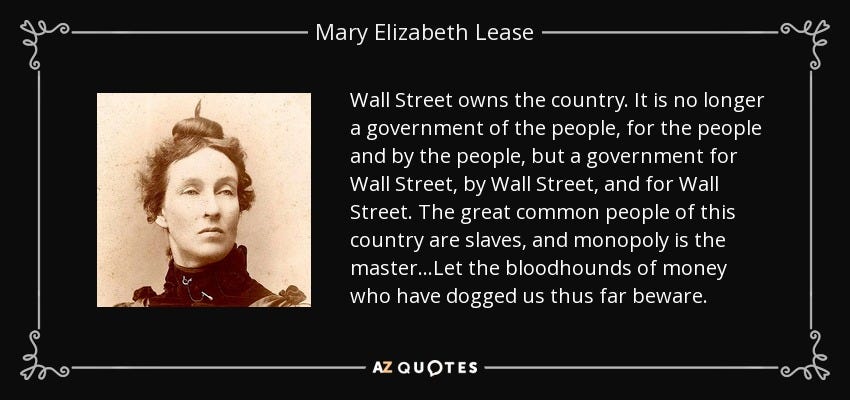

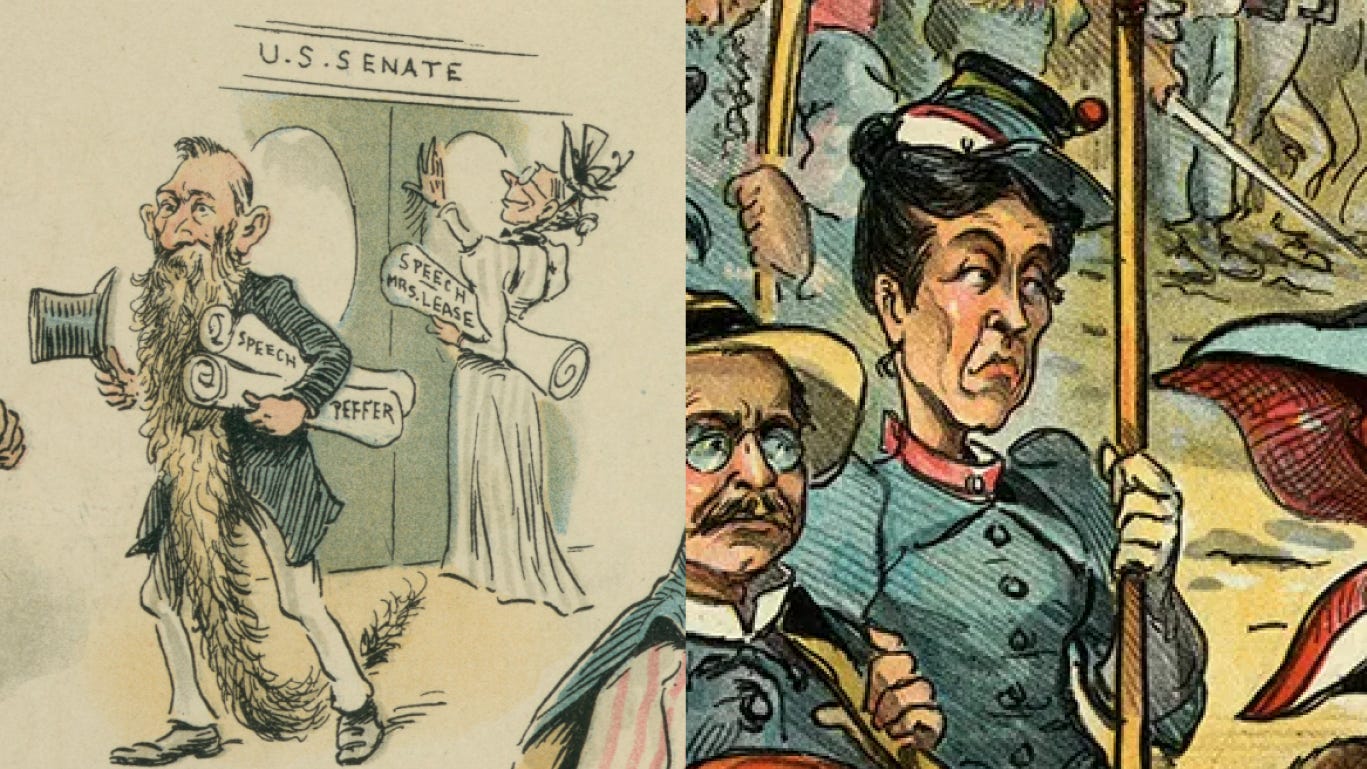

Littlefield also suggested that Dorothy represents Mary Elizabeth Lease, a daughter of Irish immigrants from Pennsylvania who moved to Kansas and turned to activism in the 1880s as economic conditions worsened for small farmers. She became the leading voice of the populist movement.

Newspapers referred to her as “The Joan of Arc of the Kansas prairies”. She was often caricatured as a female demagogue or a “Pythoness”, accused of leaving her domestic duties for the stage.

Her core demands included:

the free and unlimited coinage of silver (bimetallism) to increase the money supply and alleviate farmers' debts

Government ownership and regulation of railroads to end monopolistic practices

A graduated income tax to redistribute wealth

Direct election of senators aiming to give more power to the common people

Her fiery rhetoric famously encouraged farmers to "raise less corn and more hell," encapsulating the Populists' radical challenge to the status quo.

It’s a strong theory but often contested by Baum scholars who note Baum repeatedly stated that his stories are meant as escapist fantasy for children. He states as much in the introduction of Oz.

But given the sheer amount of parallels, it’s more difficult NOT to consider Oz to be allegorical.

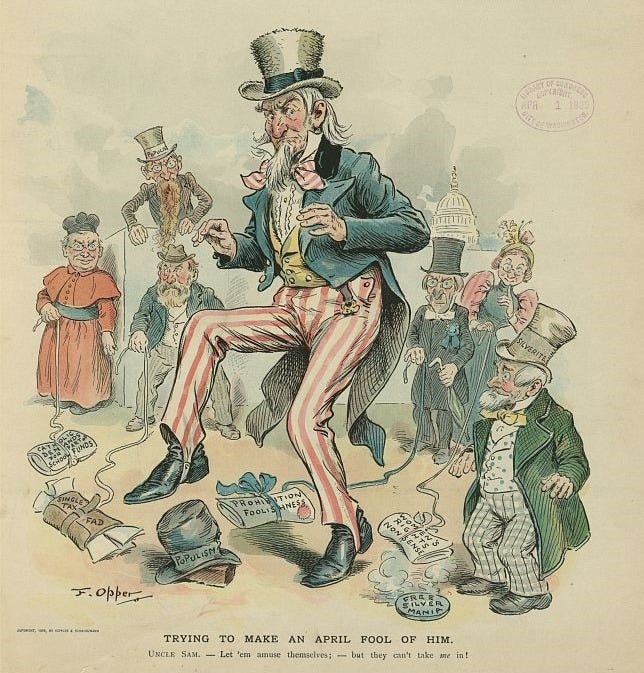

But the theory starts to make sense when you look at the political cartoons of the era. There are characters and elements that are very similar to the drawings by Oz Illustrator WW Denslow.

Puck The Populists

Puck and Judge magazines were two of the most influential illustrated humor and political satire weeklies of the late 19th century.

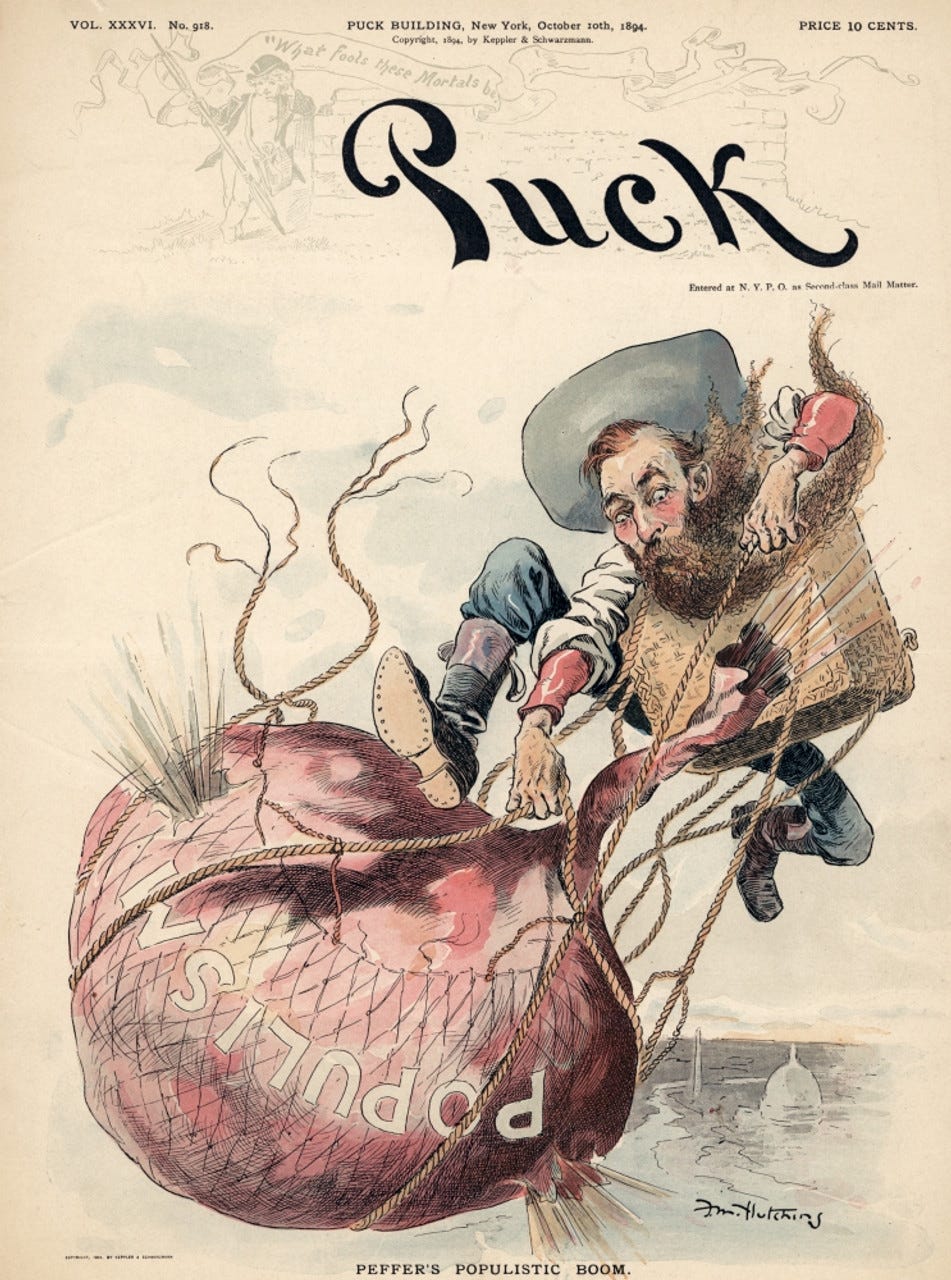

Puck cartoons also contain the seeds of many of the characters that will find their way into Oz.

Primarily backed by business interests, industrialists, and segments of the Republican Party, they played a significant role in shaping public opinion, particularly regarding the Populist movement.

1891

The leaders of the Populist party (Including the Father of Populism William Alfred Peffer) are being elevated by a patchwork of labor groups, farmers, currency reformists, socialists and (allegedly) a lot of hot air.

In the book, the Oz turns out to be a humbug (a fraud) from Omaha, Nebraska who arrived in Oz via a hot air balloon that was carried away by a storm.

1894

After the arrest of Coxey, the same balloon imagery from Judge is used by Puck to again depict Peffer in a hot air balloon (Populism) this time losing altitude over the Capitol.

Mary Elizabeth Lease rose to prominence in the early 1880s as the new fiery voice of the Populist movement. She began touring the Midwest and South, delivering speeches that attacked Wall Street, the railroads, and the two-party system.

1895

“Out Nebraska Way” by Louis Dalrymple from 1895 depicts a fence-sitting farmer reading free silver newspapers. A personification of new American Progress is shown as holding “Sound Money” (a gold standard) urging the farmer to get back to work. But the farmer is concerned about “gold bugs” eating his profits.

The scene is very reminiscent of when Dorothy meets the Scarecrow. In the book, he complains about the crows eating his corn. For context: the average farmer was making about $1 out of $10.50.

In this Puck carton by Frederick Burr Opper, Uncle Sam is depicted as inching through a minefield of political issues while eyeing a man labeled a silverite.

The Silverite (possibly a mine owner) is dressed almost exactly like the Wizard of Oz. Also note the figure in black behind him with a blue ribbon tied to temperance and prohibition. This person looks very similar to the wicked witch of the West.

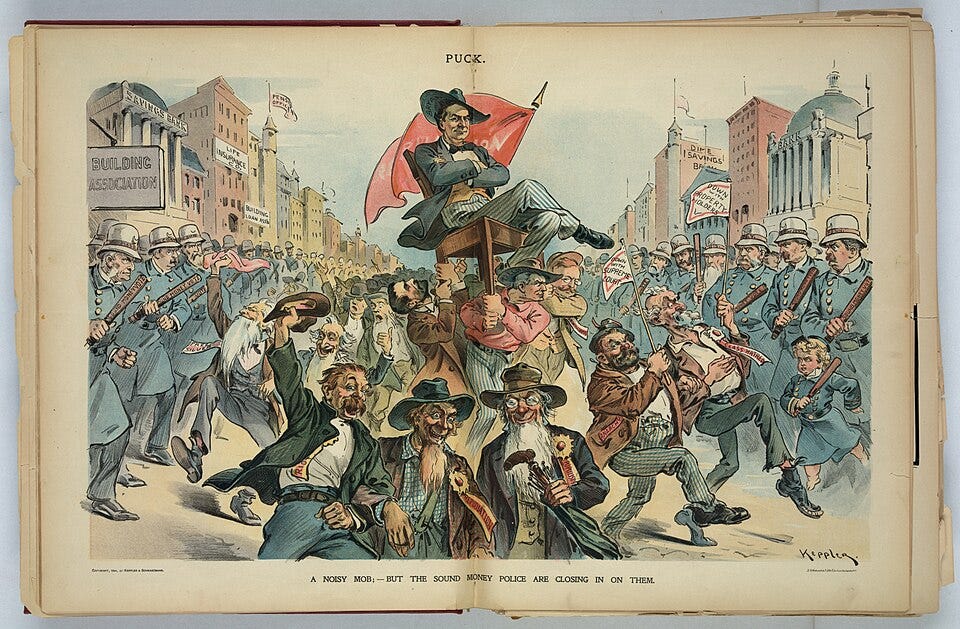

In the summer of 1896, the People’s Party (by then, America’s largest organized movement of tenant farmers, laborers, and disillusioned middle-class reformers) gathered in St. Louis, Missouri for what would be its most consequential and divisive convention.

1896

J. Udo Keppler sarcastically depicts the 1896 Election as a “Peace Jubilee” and Lease as the Goddess Columbia, the symbolic representation of America.

Lease and others in the “Mid-road Populist” camp warned against any alliance with the Democrats, fearing it would dilute the movement’s radical agenda. But the party faced a seductive proposal: fusion.

That proposal came in the form of William Jennings Bryan, the young Democratic candidate from Nebraska.

Artist J S Pughe illustrated the “friends” of Bryan; “Pitchfork Ben” aka Tillman, who represented the average farmer and a labor protestor reimagined as an anarchist rioter. The Tiger refers to head of Tammany Hall, Boss Tweed (who was known as a “the tiger”) was a political leader in the Democratic Party. Tweed and Bryan had no affiliation.

Tiger-headed creatures called “Kalidahs” guard the threshold of the Emerald City in Oz.

The farmers and laborers supporting Bryan are depicted as backwoods lunatics.

At the Democratic Convention in Chicago just days earlier, Bryan had delivered what would become one of the most famous speeches in American political history: the “Cross of Gold” speech. He railed against the deflationary gold standard that had devastated the working class.

“You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns;

You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

-Bryan

Leading up to the election artist L. Dalrymple depicts the gold standard as a woman escorted by Dem incumbent Grover Cleveland who is “well-protected” from Bryan and minorities in the Populist alley. Lease is pictured in the background, coded red for socialist/anarchist.

Cleveland was a Democrat but also a supporter of the gold standard. Cleveland also officially put a stop to the minting of silver in 1893 (in response to the Panic) which is what sparked Coxey’s army into action.

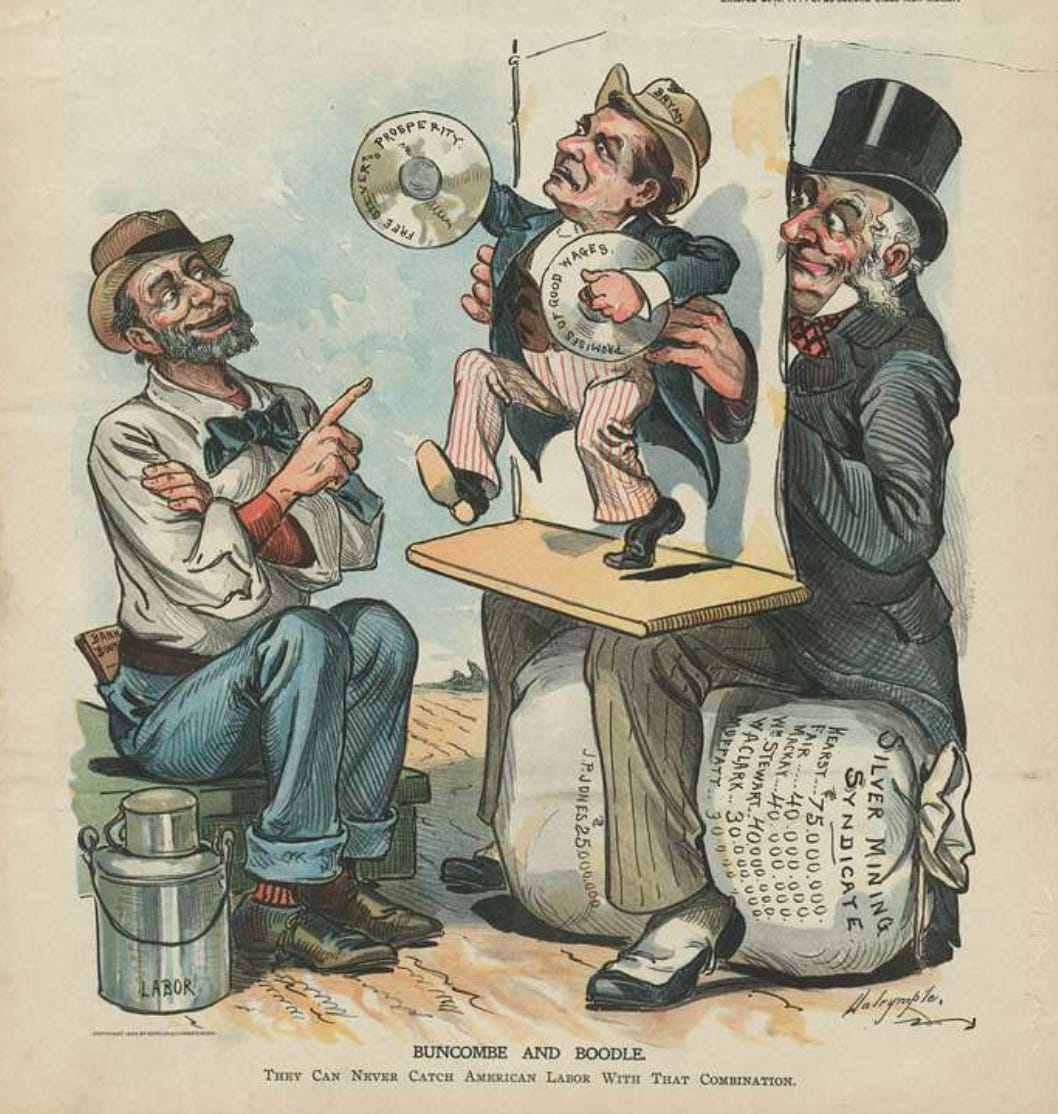

Here Bryan is depicted as a puppet of the Silver Mining syndicate.

While silver miners did support the Free Silver movement, Bryan also had the backing of many grassroots groups.

In this image you can see Coxey and Lease, along with many other labor leaders behind Bryan.

The vote was wrenching. In the end, the Populist Convention nominated Bryan (endorsing the Democratic candidate) but chose their own vice presidential nominee, Thomas E. Watson, in an effort to maintain some independence.

The result was disastrous. The fusion ticket confused voters and splintered the party.

Bryan lost the election to Republican William McKinley, who was backed by powerful industrial capital. And with that defeat, the Populist movement began its slow collapse, absorbed by the very system it had sought to challenge.

This cover depicts the Republican win as also a win for conservative suffragettes. Democrats are shown with a flat tire, while the Populists head off into a ditch. The main character in gold may be a composite of McKinley and Frances Willard, who had just written a popular book about learning to ride a bike at 53.

Lease, outraged by the compromise, largely withdrew from national politics.

Post election, Puck showed the farmer and the democratic party as having been hit by the sentiment of “sound money” and left hung out to dry.

In Oz, The Scarecrow ends up hung out to dry like this.

In this 1899 Puck cartoon titled "Deserting the Old Idol" by Dalrymple, Bryan is show as abandoned by voters. The population march with Columbia, (prosperity) the spirit of manifest destiny, leading them away from the gray flat landscape and the aging agrarian, towards the white buildings of Washington and regular two-party politics. The agrarian and populist movement are covered in cobwebs. When Dorothy finds the tin Woodman, he’s in a similar state.

In fusing with Bryan, the Populists had gambled everything.

This also put Republicans in control of the US for 32 years.

It marked a significant and enduring shift in political allegiances and issues. The era following (known as The Fourth Party System) saw the rise of Eugenics and the re-emergence of the KKK and ended with the (3rd) Great Depression.

The Old Deal

In a strange twist of American political fate, the radical demands of Coxey’s Army, dismissed as utopian or anarchist in 1894, were largely realized four decades later under the New Deal. What the Populists and Commonwheelers envisioned as heresy became federal policy during the Great Depression.

in 1935 (41 years later) President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal would enact programs that looked eerily similar:

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired millions to build roads, schools, and parks—the exact type of jobs Coxey demanded.

The Social Security Act institutionalized a safety net for the poor and elderly.

The Federal Reserve and banking reforms acknowledged the failures of private finance Coxey had warned against.

Fiat currency expansion and the gold standard’s suspension mirrored Coxey’s call for government-issued money.

Just 3 years later, production began on a film adaptation of Wizard of Oz.

In May 1944, during World War II, Jacob Coxey (90 years old) was invited back to Washington, D.C. to deliver the speech he was denied in 1894. This time, he stood on the Capitol steps as an honored guest. The ideas that had once branded him a crank had become patriotic common sense. 1944 would also see a re-release of the Wizard of Oz which had already become a beloved American classic.

Thanks for putting out such an interesting piece about the historical connections in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz!

I also wrote a post about some covert themes that created the characters in Oz. https://valeriethornton.substack.com/p/how-the-wizard-of-oz-connects-to