Today, many descendants of European settlers express anxiety over immigration, fearing an erosion of the “civilized” culture they believe defines their national identity. Yet not long ago, their own ancestors arrived uninvited on shores already home to societies rooted in sustainability, kinship, and tradition.

Thanksgiving offers a symbolic contradiction: a holiday celebrating mutual aid between settlers and Native Americans, even as current political discourse demonizes newcomers. The original inhabitants of this land hunted responsibly on ancestral grounds, maintained ecological balance, and limited family size to preserve resources. To Christian settlers, such restraint appeared unnatural—even weak. Invoking a divine mandate to “be fruitful and multiply,” they expanded ceaselessly into lands already inhabited.

Like Gilgamesh, who convinced the wild man Enkidu to abandon the forest and enter the city, settlers promised civilization would bring safety, purpose, and immortality. But, as in the ancient myth, that promise came with a hidden cost.

The American System

After the Revolutionary War, the United States needed more than survival—it needed a story of greatness. Henry Clay’s “American System” offered one: a blueprint for national unity and prosperity, built on three pillars—protective tariffs to grow industry, federally funded infrastructure to knit distant regions together, and a national bank to stabilize currency and credit.

To many, this was civilization made tangible: roads instead of trails, banks instead of barter, markets instead of mutual aid.

But for those whose lives stood in its way (Indigenous peoples and enslaved laborers)

it was a system of expansion, not inclusion.

Andrew Jackson, the rough-hewn general from the frontier, positioned himself as the unlikely champion of this national vision. Early in his career, he supported its goals: building roads, expanding the economy through conquest, and reaping the benefits of federal power. But as wealth pooled in elite hands and national debt mounted, Jackson soured. He began to see the bank as corrupt, infrastructure as favoring the rich, and coexistence with Native Americans as a naive fantasy.

By the time he reached the presidency, Jackson had turned against Clay’s system entirely. His solution? Expand by other means: through war, land seizures, and the raw will of self-made men.

Red Sticks and Rifles

The conflict came to a head in 1813, when violence at Fort Mims between Creek factions gave Jackson (then a militia general) the justification he needed to escalate frontier warfare. As chronicled in Steve Inskeep’s Jacksonland, Jackson and his ally John Coffee secured vast Native lands through coercive treaties crafted to benefit settlers. Forests and hunting grounds were cleared for cotton, feeding a global market made ravenous by Europe’s textile demand and Eli Whitney’s cotton gin.

In the name of civilization, Jackson decimated it.

His actions didn’t just dispossess Native Americans; they also reinvigorated American slavery. Cotton, once in decline, became the new gold. Jackson’s own slave-holdings ballooned (from fewer than a dozen to over 150!) making him one of the wealthiest men in Tennessee.

Publicly, he adopted a Native child and petitioned for the boy’s admission to West Point, styling himself as a benevolent patriarch. Privately, he exploited land, labor, and power with ruthless ambition. It is said he once rode two horses to death in a single journey, driven to prove a point. That image lingers: the settler riding civilization itself to exhaustion.

Like Gilgamesh, who dragged Enkidu into the city to tame him,

Jackson dressed domination as salvation.

But the cost of that promise became clear. The cotton economy collapsed from overproduction. His adopted son died young from tuberculosis—like many enslaved workers exposed to cotton dust. And Jackson’s political ascent destroyed his wife Rachel, who withered under the public attacks that came with her husband’s rise.

Jackson’s contradictions were not personal quirks. They were the contradictions of America itself: born in trauma, convinced of its righteousness, expanding through violence, and unsure how to grieve what it destroys.

Echo Chambers, Then and Now

Jackson didn’t rise alone. He was carried by an echo chamber.

Partisan newspapers of the era functioned like today’s social media—amplifying division, stoking outrage, and reinforcing tribal identities. His populist image was carefully constructed through editorials painting him as a champion of the common man and a scourge of elite corruption. But these same outlets dehumanized Native Americans and fueled support for their removal, even when many had adopted Christian faith, written constitutions, and lived peacefully.

Jackson may have once believed in integrating Native Americans. But the press, political winds, and hunger for land hardened his stance. Removal became policy. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 sealed the fate of the Trail of Tears—a forced march that betrayed even those tribes who had tried to play by the rules.

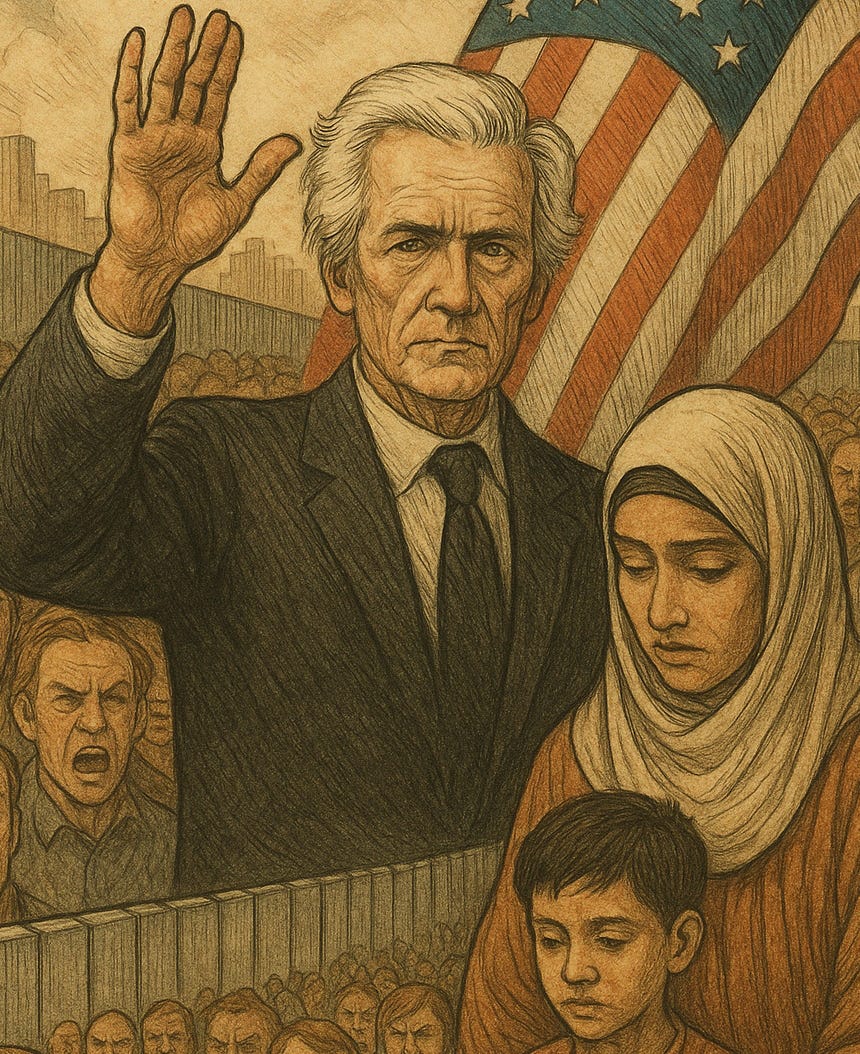

That betrayal echoes today. Digital platforms, like the newspapers of old, shape who we see as citizens, and who we frame as threats to civilization. Immigrants are cast as invaders. Minorities seeking inclusion are painted as radicals. A nation built on erasure now fears being erased.

Enkidu’s Bargain

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu gives up the wilderness for bread, wine, and clothing.

But his strength fades. He grows ill, and dies longing for the freedom he abandoned.

The myth warns us: civilization, once offered as salvation, can become a cage. Its comforts dull the senses. Its rules protect power. It asks us to forget the wild, to abandon humility, to accept that some lives matter less.

African Americans know this bargain well. In Jackson’s time, they built the wealth of the nation but were barred from its promises. After Emancipation, new gates rose: Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration. Even now, equality is framed as “wokeness” and punished as disruption. The city’s doors may appear open, but the burden of entry is unevenly carried.

And so we return to the question of who belongs. Today, many who inherited the spoils of expansion cry foul at the arrival of newcomers (particularly migrants from the “Global South” or Muslim-majority countries) casting them as threats to a civilization they themselves did not build but merely inherited.

The irony runs deep: the descendants of settlers, who arrived without invitation, now patrol the gates of belonging with amnesia and entitlement. They forget that the very civilization they claim to defend was made possible through the labor of the enslaved, the erasure of the Native, and the sacrifice of the immigrant. To exclude others now on the basis of birthplace, language, or faith is not a defense of civilization, it is a denial of its origins.

What is civilization?

Is it roads and banks, or the values they claim to serve? Can a society that relies on conquest, exclusion, and ecological collapse still call itself civilized?

Maybe civilization isn’t a destination, but a discipline. A choice. Not conquest, but coexistence. Not domination, but stewardship.

The myth of Gilgamesh was never just about building cities. It was about remembering what we lost in the process and deciding whether we’re brave enough to live differently.

—Mallon